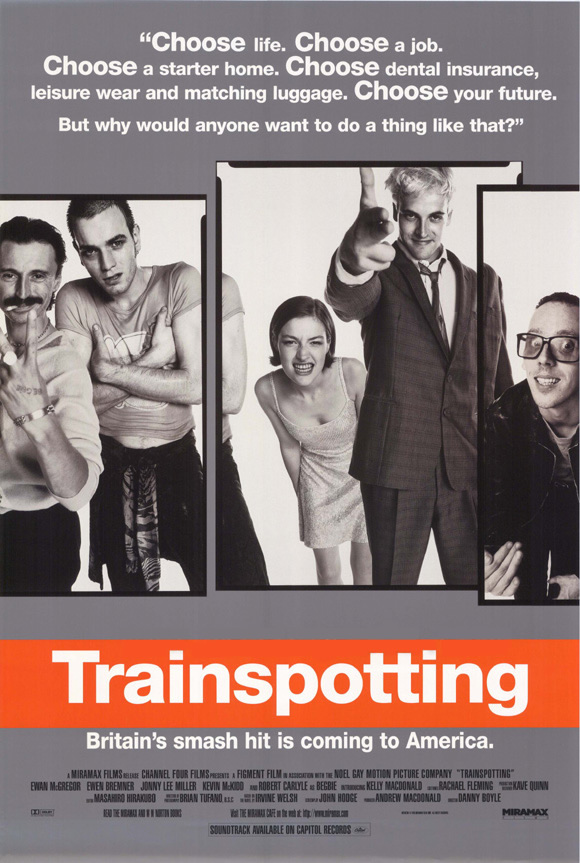

Director: Danny Boyle, 1996.

When I was in college I had a friend who knew all the train engines of Great Britain, such as the 1010 Western Campaigner. His pastime was trainspotting. But the trainspotting of this movie has nothing to do with that harmless hobby. The title actually refers to a scene in the book by Irvine Welsh that does not appear in the film. However, the term also refers to the shooting up of heroin, and is so called because of the "train-track-like" marks in the veins and also the locomotive-like hit of the heroin as it enters the blood-stream.

Boyle set his second film in the underbelly of working-class Edinburgh and gives this a distinctively British feel. Harrowing at times, hilarious at others, this is a film lauded as one of the all-time best British films; yet it requires an iron stomach since it is tough to watch.

Reunited with Ewan McGregor, Boyle builds Trainspotting around McGregor's character of Renton, the antihero. With strong Scottish brogues throughout it is often hard to decipher what is being said . . . except for the cussing, which is ubiquitous. Although it captures the essence of the subculture, it is grinding, as is the graphic portrayal of drug-use.

While some movies gloss over the impact of drug use and abuse, focusing on the seductive appeal to users, Trainspotting brings a gritty realistic treatment to this topic. Renton and his friends, Spud (Ewen Bremner) and Sick Boy (Jonny Lee Miller), are hard-core heroin addicts who cannot hold down jobs. They are joined by Tommy (Kevin McKidd), a fitness freak who avoids drugs and Begbie (Robert Carlyle), a hard-man who does people not drugs, fighting and stabbing for fun in pubs. Living in poverty and squalor, this is the story of the degeneration of these relationships; it is the story of friendships destroyed by drugs.

While some movies gloss over the impact of drug use and abuse, focusing on the seductive appeal to users, Trainspotting brings a gritty realistic treatment to this topic. Renton and his friends, Spud (Ewen Bremner) and Sick Boy (Jonny Lee Miller), are hard-core heroin addicts who cannot hold down jobs. They are joined by Tommy (Kevin McKidd), a fitness freak who avoids drugs and Begbie (Robert Carlyle), a hard-man who does people not drugs, fighting and stabbing for fun in pubs. Living in poverty and squalor, this is the story of the degeneration of these relationships; it is the story of friendships destroyed by drugs.As it starts, Renton gives an extended voice-over narration (minus the swearing):

Choose Life. Choose a job. Choose a career. Choose a family. Choose a big television, choose washing machines, cars, compact disc players and electrical tin openers. Choose good health, low cholesterol, and dental insurance. Choose fixed interest mortgage repayments. Choose a starter home. Choose your friends. . . . Choose your future. Choose life... But why would I want to do a thing like that? I chose not to choose life. I chose somethin' else. And the reasons? There are no reasons. Who needs reasons when you've got heroin?So, at the very outset, the setup is clear. There are two choices in life: Life and Heroin. Life, here, stands for the ordinary life of boredom and routine. It is the establishment. It is mind-numbing and spirit-crushing. To choose life is to give in to the man, to be like one of the humans in The Matrix, crushed and living aimless and inevitable lives; it is to be like cows destined for the slaughterhouse. On the other hand, Heroin stands for a life of excitement and ecstasy. It is anti-establishment. It is subversive and counter-cultural. It is authentic and individual. To choose heroin is to be yourself, living how you want, not accepting the destiny defined by society but paving your own way. It is mind-expanding and spirit-lifting . . . at least while the drug rushes through the veins. Once it is done, it is a different matter.

Renton has made his choice. His lifestyle is care-free, one of drugs, casual sex, drinking, raves, and he has no responsibilities. With no job, he and his friends steal, lie, cheat or do anything to get the money to buy more drugs for their next fix and the ensuing high. All is going "well" until during one of their extended highs the baby of one of the girlfriends dies in his crib. They arouse from their drug-induced stupor to this dreadful discovery. And their reaction: cook up another shot to take away the pain.

Renton has made his choice. His lifestyle is care-free, one of drugs, casual sex, drinking, raves, and he has no responsibilities. With no job, he and his friends steal, lie, cheat or do anything to get the money to buy more drugs for their next fix and the ensuing high. All is going "well" until during one of their extended highs the baby of one of the girlfriends dies in his crib. They arouse from their drug-induced stupor to this dreadful discovery. And their reaction: cook up another shot to take away the pain.When Renton's parents intervene to help him come off heroin cold turkey, locking him in his room, Boyle gives a painfully clear picture of withdrawal. With surreal visions of friends giving counsel and a baby crawling across the screen, Renton's room feels like a cell in a psychiatric ward. But he somehow comes clean. And decides to move to London, away from his no-good friends.

You can run, but you can't hide, as they say. And first Begbie, a fugutive needing a hiding place, finds him and moves in. Then Sick Boy comes south with a plan for a drug scam. Finally, Spud joins them all. Of course, Renton gets caught up, once again, in the heroin lifestyle, and falls of the wagon.

Boyle balances the depressing picture of this empty life with surreal humor. This humor is simultaneously both disgusting and funny. It is literally toilet humor.

Boyle balances the depressing picture of this empty life with surreal humor. This humor is simultaneously both disgusting and funny. It is literally toilet humor.One of the underlying themes of Trainspotting is the poverty that is endemic in urban centers like Edinburgh. And with such poverty comes a sense of hopelessness. It is tough for those caught in this trap to see a way out. And without hope, some gravitate to the easy way out, a false hope from pharmaceuticals. But there is hope, even for the most hopeless in the worst situations. That hope is found in Jesus (Col. 1:27). He can offer life and hope to those who will come to him and cling to him. He does not promise to magically make everything right in this life, though he will one day. He does promise to make it easier to live in the here and now while waiting for the future hope.

Trainspotting shows how the drug-using lifestyle leads not to hope and a beautiful future, but to death and a dead-end future. As Renton lies to those around him, to his friends, to his parents, and even to himself, he still thinks he is in control of his habit. He still thinks he can do just one more fix with no ill effect. But his choice of Heroin has enormous impact on those around him. It leads to prison for one friend, to addiction and death for another, to death of a baby for a third. Here is not life; here is deceit, decay, disintegration and death.

Yet, Trainspotting ends with a ray of hope, an ambiguous vision of what might be. It raises a question of whether rehabilitation is possible for the deeply addicted user. Though it appears that recidivism is almost certain, there is a chance that reform may remain. After the drug deal, where Hugo from Shallow Grave shows up, Renton walks away with a bag-load of money. Then, narrating the last lines, he returns to the themes of the prolog, the theme of "choice." Repeating the monolog, almost word for word, he ends with, "The truth is that I'm a bad person. But, that's gonna change -- I'm going to change. This is the last of that sort of thing. Now I'm cleaning up and I'm moving on, going straight and choosing life. I'm looking forward to it already. I'm going to be just like you." He has it right, that he is a bad person. That's true from the movie and ethically. Will he change? The cynic would answer no, he has tried and failed before; he will fail again. The optimist would answer yes, he is away from his friends who would suck him back into the life he is leaving; with these influences removed he will be able to suceed this time. The realist recognizes that life is ambiguous. There is always hope. There is always a second chance.

Although it may seem strange, Renton is in some ways like Jesus. Renton was railing against the authorities, seeking an alternative way to live. But the dichotomy he proposes is a false dichotomy. The choice we face is not between Life as defined in Trainspotting and Heroin. It is not between conventional routine and boredom or anti-establishment self-centered indulgence, whether in drugs or other forms of escapism. No, there is a third choice. Jesus gives us this option. Jesus was a counter-cultural revolutionary himself. He preached a subversive message, and its core content is found in the Sermon on the Mount (Matt. 5-7). His offer is one that is anti-establishment but it is focused on selfless giving. We don't have to settle for the consumeristic choice of the TV, the large house, the cars, the toys, the things. He offers a life that transcends this by looking outward and upward rather than inward.

Where Shallow Grave was a superficial black comedy-thriller about degeneration of relationships centered on stolen money, Trainspotting is a deeper black comedy about the degeneration of relationships centered on the deadly destructiveness of drug use. It is a hard pill to swallow, but it offers some insight into the heroin lifestyle and a hope of a redemptive journey. We can and must choose life. But what kind of "life" will you choose?

Copyright ©2008, Martin Baggs

Bullying is one of the underlying themes of Choking Man. Not only is Jorge browbeaten at work, but his room-mate is domineering, telling him what to do. When he realizes Jorge has some affection for Amy, he tells him to choke Jerry and kill him. Like

Bullying is one of the underlying themes of Choking Man. Not only is Jorge browbeaten at work, but his room-mate is domineering, telling him what to do. When he realizes Jorge has some affection for Amy, he tells him to choke Jerry and kill him. Like  One scene stands out. In trying to reciprocate and perhaps reach out with a shy, romantic love, he wants to give Amy a gift. He sees a red Chinese dragon in a pawnshop window. Summoning up the courage to enter, itself a victory, he asks about the toy in the window. The owner brings an Elmo doll, and Jorge is unable to communicate what he wants. You can feel the frustration at lack of communication and at his sense of being a stranger in a strange land.

One scene stands out. In trying to reciprocate and perhaps reach out with a shy, romantic love, he wants to give Amy a gift. He sees a red Chinese dragon in a pawnshop window. Summoning up the courage to enter, itself a victory, he asks about the toy in the window. The owner brings an Elmo doll, and Jorge is unable to communicate what he wants. You can feel the frustration at lack of communication and at his sense of being a stranger in a strange land.

Even at Hogwarts new surprises emerge, such as wizard duels. It is during one of these that Harry learns that he is a parselmouth, a talent usually limited to Slytherins: he can speak to snakes. Then

Even at Hogwarts new surprises emerge, such as wizard duels. It is during one of these that Harry learns that he is a parselmouth, a talent usually limited to Slytherins: he can speak to snakes. Then Although

Although  A key issue raised in

A key issue raised in

Cut to North Africa, where Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg (Tom Cruise) is writing treasonous thoughts in his journal. Clearly, he is no Nazi. He has come to a conclusion: "I'm a soldier, but in serving my country, I have betrayed my conscience." He has faced the truth and it is not pretty. At that very moment, incoming allied fighter planes swoop down to strafe his men and tanks, and he is severely wounded. The next time we see him, he is missing his right hand, two fingers of his left hand and one eye.

Cut to North Africa, where Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg (Tom Cruise) is writing treasonous thoughts in his journal. Clearly, he is no Nazi. He has come to a conclusion: "I'm a soldier, but in serving my country, I have betrayed my conscience." He has faced the truth and it is not pretty. At that very moment, incoming allied fighter planes swoop down to strafe his men and tanks, and he is severely wounded. The next time we see him, he is missing his right hand, two fingers of his left hand and one eye. The first part of the film focuses on Stauffenberg the man. He is a husband and a father. He shares his participation in the conspiracy with his wife Nina (Carice van Houten, from the recent Dutch WW2 film,

The first part of the film focuses on Stauffenberg the man. He is a husband and a father. He shares his participation in the conspiracy with his wife Nina (Carice van Houten, from the recent Dutch WW2 film,  The second half of the film moves into the execution of the plan. On July 20, 1944, Hitler convened a war council at the heavily guarded "Wolf's Lair." Stauffenberg takes the bombs with him. Then, relying on support from General Olbricht back in Berlin, Stauffenberg expects him to force General Fromm (Tom Wilkinson), the commander of the reserve army, to execute their plans. But Fromm is hedging his bets and comes down with Hitler. Olbricht, on the other hand, has lost his nerve. Stauffenberg is on his own. And the closing act shows Stauffenberg as a natural leader who takes all decisions upon himself.

The second half of the film moves into the execution of the plan. On July 20, 1944, Hitler convened a war council at the heavily guarded "Wolf's Lair." Stauffenberg takes the bombs with him. Then, relying on support from General Olbricht back in Berlin, Stauffenberg expects him to force General Fromm (Tom Wilkinson), the commander of the reserve army, to execute their plans. But Fromm is hedging his bets and comes down with Hitler. Olbricht, on the other hand, has lost his nerve. Stauffenberg is on his own. And the closing act shows Stauffenberg as a natural leader who takes all decisions upon himself.

It's now 1954 and a week before Christmas. Their show is winding up for a Christmas break in Florida. They are like an old married couple, arguing and fighting but still loving each other. Wallace is a workaholic, wheeling and dealing and working the angles. Davis is a commitmentless womanizer who wants a little more spare-time. At a request from an old army buddy, they agree to listen to a sister act, Judy Haynes (Vera-Ellen) and Betty Haynes (Rosemary Clooney), before taking the train to New York. As they sing their song, "Sisters," these sisters win over the men.

It's now 1954 and a week before Christmas. Their show is winding up for a Christmas break in Florida. They are like an old married couple, arguing and fighting but still loving each other. Wallace is a workaholic, wheeling and dealing and working the angles. Davis is a commitmentless womanizer who wants a little more spare-time. At a request from an old army buddy, they agree to listen to a sister act, Judy Haynes (Vera-Ellen) and Betty Haynes (Rosemary Clooney), before taking the train to New York. As they sing their song, "Sisters," these sisters win over the men. With the police looking for the sisters to arrest them, they need an angle and a friend. Through some contrivances, the sisters get the men's tickets to Vermont, and the men agree to go there with them to enjoy the snow. Coincidence abounds when the owner of the sun-soaked and snow-challenged resort turns out to be Gen. Waverley, retired and almost bankrupt. So, Davis and Wallace decide to bring their production to his hotel as away to attract an audience. A further idea is to reunite all the men from the division for their 10th anniversary on Christmas Eve. The narrative plot is defined. Can the two soldier-performers help save their popular general? Can Bob and Betty hit it off? And will there be snow on Christmas Eve? These three plot-lines weave together to arrive at a well-known and predictable climax.

With the police looking for the sisters to arrest them, they need an angle and a friend. Through some contrivances, the sisters get the men's tickets to Vermont, and the men agree to go there with them to enjoy the snow. Coincidence abounds when the owner of the sun-soaked and snow-challenged resort turns out to be Gen. Waverley, retired and almost bankrupt. So, Davis and Wallace decide to bring their production to his hotel as away to attract an audience. A further idea is to reunite all the men from the division for their 10th anniversary on Christmas Eve. The narrative plot is defined. Can the two soldier-performers help save their popular general? Can Bob and Betty hit it off? And will there be snow on Christmas Eve? These three plot-lines weave together to arrive at a well-known and predictable climax. Director: Robert Zemeckis, 2004.

Director: Robert Zemeckis, 2004. While on the train the conductor gives the boy a ticket with the letters B and E punched out. On the ride he encounters a hobo. They begin to discuss the existence of Santa. The boy states that he wants to believe but, as the hobo points out, is afraid he might be wrong; the truth may be that Santa is not real and what would Christmas be without Santa? The hobo sympathizes with the boy’s dilemma and says to him, “Seeing is believing, am I right?” If he sees then he will believe.

While on the train the conductor gives the boy a ticket with the letters B and E punched out. On the ride he encounters a hobo. They begin to discuss the existence of Santa. The boy states that he wants to believe but, as the hobo points out, is afraid he might be wrong; the truth may be that Santa is not real and what would Christmas be without Santa? The hobo sympathizes with the boy’s dilemma and says to him, “Seeing is believing, am I right?” If he sees then he will believe. During the train ride the boy speaks with the conductor who tells a story of being rescued from falling off the train by someone or “something” unseen. In contrast to the hobo, the conductor points out that sometimes “the most real things in the world are the things we can’t see.” For our hero, the dilemma is clearly presented: will he believe even if he can’t see?

During the train ride the boy speaks with the conductor who tells a story of being rescued from falling off the train by someone or “something” unseen. In contrast to the hobo, the conductor points out that sometimes “the most real things in the world are the things we can’t see.” For our hero, the dilemma is clearly presented: will he believe even if he can’t see? Finally, arriving at the North Pole, the children get to join the elves in witnessing Santa emerge and begin his delivery of presents. First the reindeer are brought out with sleigh bells attached. However, our hero can’t hear the bells or see Santa. Then one bell flies through the air and falls silently before him. He picks it up and stares at it. After a long pause he confesses, “I believe,” and shaking the bell he hears it ring. He then hears the reindeers' sleigh bells. His hope has finally come true.

Finally, arriving at the North Pole, the children get to join the elves in witnessing Santa emerge and begin his delivery of presents. First the reindeer are brought out with sleigh bells attached. However, our hero can’t hear the bells or see Santa. Then one bell flies through the air and falls silently before him. He picks it up and stares at it. After a long pause he confesses, “I believe,” and shaking the bell he hears it ring. He then hears the reindeers' sleigh bells. His hope has finally come true. It makes sense that the boy would want one of the bells for a Christmas present to remind him that Santa was real. Giving him the bell, Santa explains that he and the bell are simply symbols of the spirit of Christmas. The true spirit of Christmas lies in your heart. When the boy returns to the train the conductor completes punching the letters on his ticket to spell: BELIEVE.

It makes sense that the boy would want one of the bells for a Christmas present to remind him that Santa was real. Giving him the bell, Santa explains that he and the bell are simply symbols of the spirit of Christmas. The true spirit of Christmas lies in your heart. When the boy returns to the train the conductor completes punching the letters on his ticket to spell: BELIEVE.

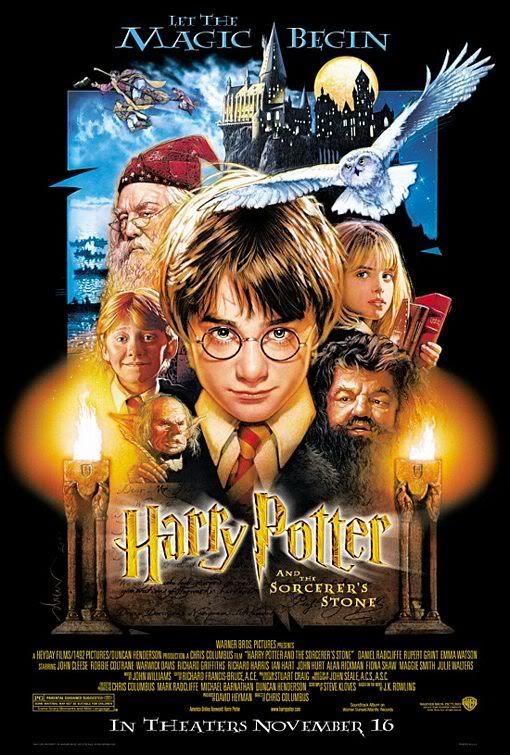

lank-haired Alan Rickman. It also gave us a memorable John Williams score, to go alongside his other famous film compositions of the last 20 years (e.g., Star Wars, Jaws, ET, Raiders of the Lost Ark, and so many more).

lank-haired Alan Rickman. It also gave us a memorable John Williams score, to go alongside his other famous film compositions of the last 20 years (e.g., Star Wars, Jaws, ET, Raiders of the Lost Ark, and so many more). As Harry (Daniel Radcliffe) befriends loyal Ron Weasley (Rupert Grint) and studious Hermione Grainger (Emma Watson), he sets the stage for this movie and those to come. This is a trio that will stick together like glue. At the end of the film when Harry compares himself and his cleverness to Hermione's, she responds, "There are more important things: friendship and bravery." These are the themes of this first film, and they will reappear throughout the long series. Much could be said of these themes. They resonate with the human heart. They fill the works of great literature. They show up in the bible. They are true to life, because they are at the heart of life.

As Harry (Daniel Radcliffe) befriends loyal Ron Weasley (Rupert Grint) and studious Hermione Grainger (Emma Watson), he sets the stage for this movie and those to come. This is a trio that will stick together like glue. At the end of the film when Harry compares himself and his cleverness to Hermione's, she responds, "There are more important things: friendship and bravery." These are the themes of this first film, and they will reappear throughout the long series. Much could be said of these themes. They resonate with the human heart. They fill the works of great literature. They show up in the bible. They are true to life, because they are at the heart of life. Another sub-plot centers around the hidden Mirror of Erised. This is no ordinary mirror. A magical mirror, it reflects the desires of the heart not the visage of the viewer. When Harry stumbles upon it, it shows him his dead parents. This ensnares him and captivates his time and attention. Going back time after time, Dumbledore finally catches him and warns him, "It does not do to dwell on dreams, Harry, and forget to live." This is excellent advice. There is a place for dreams, if they inspire us and motivate us for the better. But if we get so wrapped up in the dream, as Harry did, then we stop enjoying the present. We forget to live in the here and now. Dreams are supposed to help, not hinder, our pursuit of life.

Another sub-plot centers around the hidden Mirror of Erised. This is no ordinary mirror. A magical mirror, it reflects the desires of the heart not the visage of the viewer. When Harry stumbles upon it, it shows him his dead parents. This ensnares him and captivates his time and attention. Going back time after time, Dumbledore finally catches him and warns him, "It does not do to dwell on dreams, Harry, and forget to live." This is excellent advice. There is a place for dreams, if they inspire us and motivate us for the better. But if we get so wrapped up in the dream, as Harry did, then we stop enjoying the present. We forget to live in the here and now. Dreams are supposed to help, not hinder, our pursuit of life. As Sorcerer's Stone draws to its climax, Harry faces his foe, and is told: "There is no good and evil, there is only power, and those too weak to seek it." Here is the philosophy of "might makes right." It is the immorality of power, and it is a lie, both in the movie as well as in the Bible. As Satan lied to Adam and Eve in the garden (Gen. 3:1-5), so he continues to lie today (Jn. 8:44). There absolutely is good and evil. The first act of the Bible is the story of a good creation that is marred and twisted by evil; the rest of the story is that of the ultimate redemption and restoration of this creation by a good God and his ultimate triumph of good over evil. Yet, even today we live in the midst of this story, seeing the impact of evil on our world, even on our own lives and in our own characters. Yet we see glimmers of the goodness of God in acts of grace and mercy, in lives touched by his hand. So, we know innately that there is good and there is evil. Having power does not negate good and evil. Power itself is amoral, but when combined with the innate sinfulness of humanity it works its "magic." As Baron Act famously said, "Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely." Yet, Jesus had absolute power. He humbled himself to take on frail flesh (Phil. 2:6-8), and today his power is made perfect in his followers in their weakness, not their strength (2 Cor. 12:9). There is good and evil and only in weakness will Jesus-followers find power.

As Sorcerer's Stone draws to its climax, Harry faces his foe, and is told: "There is no good and evil, there is only power, and those too weak to seek it." Here is the philosophy of "might makes right." It is the immorality of power, and it is a lie, both in the movie as well as in the Bible. As Satan lied to Adam and Eve in the garden (Gen. 3:1-5), so he continues to lie today (Jn. 8:44). There absolutely is good and evil. The first act of the Bible is the story of a good creation that is marred and twisted by evil; the rest of the story is that of the ultimate redemption and restoration of this creation by a good God and his ultimate triumph of good over evil. Yet, even today we live in the midst of this story, seeing the impact of evil on our world, even on our own lives and in our own characters. Yet we see glimmers of the goodness of God in acts of grace and mercy, in lives touched by his hand. So, we know innately that there is good and there is evil. Having power does not negate good and evil. Power itself is amoral, but when combined with the innate sinfulness of humanity it works its "magic." As Baron Act famously said, "Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely." Yet, Jesus had absolute power. He humbled himself to take on frail flesh (Phil. 2:6-8), and today his power is made perfect in his followers in their weakness, not their strength (2 Cor. 12:9). There is good and evil and only in weakness will Jesus-followers find power.

four years in his father's small building and loan firm, his father dies. George defers his trip. When the firm is about to be forced to close by Mr. Potter (Lionel Barrymore), the cold-blooded miser who owns almost all of the town and wants more, there is only one hope. Only if George stays to run the company will it survive. So loyal George puts his town, his community and his friends before himself. He sacrifices his plans on the altar of community need. Later, when younger brother Harry returns from college and is expected to take over so George can himself go to school, George puts Harry's career ahead of his own, and commits to staying at the helm of the firm. He sacrifices his dreams on the altar of sibling need.

four years in his father's small building and loan firm, his father dies. George defers his trip. When the firm is about to be forced to close by Mr. Potter (Lionel Barrymore), the cold-blooded miser who owns almost all of the town and wants more, there is only one hope. Only if George stays to run the company will it survive. So loyal George puts his town, his community and his friends before himself. He sacrifices his plans on the altar of community need. Later, when younger brother Harry returns from college and is expected to take over so George can himself go to school, George puts Harry's career ahead of his own, and commits to staying at the helm of the firm. He sacrifices his dreams on the altar of sibling need. Later, to add insult to injury, on the day of his wedding to Mary (Donna Reed in her first starring role), when they are about to leave on their honeymoon, George sees something happening at the bank. Economic depression has hit home and hit hard. There is a run on the bank and then on his savings and loan. Fear causes his mom and pop investors to demand their money. Of course, the money isn't available. So, George, at the prompting of understanding and generous Mary, gives away their honeymoon-travel money to save his firm and his friends. Now he has sacrificed his savings.

Later, to add insult to injury, on the day of his wedding to Mary (Donna Reed in her first starring role), when they are about to leave on their honeymoon, George sees something happening at the bank. Economic depression has hit home and hit hard. There is a run on the bank and then on his savings and loan. Fear causes his mom and pop investors to demand their money. Of course, the money isn't available. So, George, at the prompting of understanding and generous Mary, gives away their honeymoon-travel money to save his firm and his friends. Now he has sacrificed his savings. Act three. Step in gentle Clarence. He comes down to earth on what seems an easy mission. But it is more difficult than it appears. The opening he needs appears when George wishes verbally that he had never been born. Clarence grants him his wish: "You've been given a great gift, George. A chance to see what the world would be like without you." And, in a twinkle, the world of Bedford Falls no longer exists; it is now the world of Pottersville. George's friends are now lonely, living sad, even sinful lives, having never known him. Worse, Harry is not a war hero. Harry is dead, since George was not there to save him. As Clarence tells him, "Strange isn't it? Each man's life touches so many other lives. When he isn't around he leaves an awful hole, doesn't he?"

Act three. Step in gentle Clarence. He comes down to earth on what seems an easy mission. But it is more difficult than it appears. The opening he needs appears when George wishes verbally that he had never been born. Clarence grants him his wish: "You've been given a great gift, George. A chance to see what the world would be like without you." And, in a twinkle, the world of Bedford Falls no longer exists; it is now the world of Pottersville. George's friends are now lonely, living sad, even sinful lives, having never known him. Worse, Harry is not a war hero. Harry is dead, since George was not there to save him. As Clarence tells him, "Strange isn't it? Each man's life touches so many other lives. When he isn't around he leaves an awful hole, doesn't he?" Fundamentally It's A Wonderful Life deals with life, and how wonderful it is. George's "ordinary" life had touched so many. As the wise Clarence said to George, "no man is a failure who has friends." Life is not all about money, things, achievements. It is about relationships, friends, loved ones. George was a rich man indeed. He had a beautiful wife, four healthy and cute children, and many friends. Only in his time of trial, his moment of need, do these friends come out of the woodwork and show their true colors. But they do. They know George was in need and he never asked for anything for himself. Almost everybody in Bedford Falls prays for George; almost everybody in Bedford Falls gives to George. How much more can a man want than this: family and friends who will pray and give, love and care. As Clarence says to George at the end, "You see, George, you've really had a wonderful life." When we get down and depressed, it is worth remembering this advice from Clarence. Our lives, just like George's, are too precious to throw away.

Fundamentally It's A Wonderful Life deals with life, and how wonderful it is. George's "ordinary" life had touched so many. As the wise Clarence said to George, "no man is a failure who has friends." Life is not all about money, things, achievements. It is about relationships, friends, loved ones. George was a rich man indeed. He had a beautiful wife, four healthy and cute children, and many friends. Only in his time of trial, his moment of need, do these friends come out of the woodwork and show their true colors. But they do. They know George was in need and he never asked for anything for himself. Almost everybody in Bedford Falls prays for George; almost everybody in Bedford Falls gives to George. How much more can a man want than this: family and friends who will pray and give, love and care. As Clarence says to George at the end, "You see, George, you've really had a wonderful life." When we get down and depressed, it is worth remembering this advice from Clarence. Our lives, just like George's, are too precious to throw away.

When she is a young woman she spots Pedro (Marco Leonardi), a handsome young Mexican who immediately declares his love for her. It is true love at first sight. Determined to marry her, he comes to her home to seek her mother's blessing. Taking tea with Elena, he is told this is impossible. Instead, Elena offers him her first-born, Rosaura (Yareli Arizmendi). Unlike

When she is a young woman she spots Pedro (Marco Leonardi), a handsome young Mexican who immediately declares his love for her. It is true love at first sight. Determined to marry her, he comes to her home to seek her mother's blessing. Taking tea with Elena, he is told this is impossible. Instead, Elena offers him her first-born, Rosaura (Yareli Arizmendi). Unlike  As life progresses, Tita takes over the kitchen and expresses her passion for Pedro through the dishes she prepares. Her love for cooking is surpassed only by her love for him. These delicacies are sensual indulgences that those who partake experience as never before. Much like Babette in the Danish film Babette's Feast, this is her gift to Pedro and her family.

As life progresses, Tita takes over the kitchen and expresses her passion for Pedro through the dishes she prepares. Her love for cooking is surpassed only by her love for him. These delicacies are sensual indulgences that those who partake experience as never before. Much like Babette in the Danish film Babette's Feast, this is her gift to Pedro and her family. Like Water for Chocolate is a feast for the senses. It is a slow but engaging love story. Filled with warm colors, lots of oranges and reds, it conveys their passion visually even as Tita's concoctions convey her passions gastronomically. With magical realism, ghosts appear to give counsel or criticism to Tita. But it ends leaving the viewer with two narrative questions: did Tita marry John, and did Pedro make the right decision?

Like Water for Chocolate is a feast for the senses. It is a slow but engaging love story. Filled with warm colors, lots of oranges and reds, it conveys their passion visually even as Tita's concoctions convey her passions gastronomically. With magical realism, ghosts appear to give counsel or criticism to Tita. But it ends leaving the viewer with two narrative questions: did Tita marry John, and did Pedro make the right decision?

But Hugo manages to win Juliet's attention and she persuades her fellow flat mates to let him become the fourth. No sooner is he in, than he is not seen for days, locked behind his bedroom door. When they finally kick in his door, they find him flat on his back, naked and dead on his bed. And under the bed is a suitcase of money. What to do? Juliet and David want to call the police; Alex has grander and greedier plans. He wants to keep the money and dispose of the body in the titular shallow grave. His influence wins. But David draws the short straw for the grisly job of removing all forms of identification from the body. This is the turning point in the film.

But Hugo manages to win Juliet's attention and she persuades her fellow flat mates to let him become the fourth. No sooner is he in, than he is not seen for days, locked behind his bedroom door. When they finally kick in his door, they find him flat on his back, naked and dead on his bed. And under the bed is a suitcase of money. What to do? Juliet and David want to call the police; Alex has grander and greedier plans. He wants to keep the money and dispose of the body in the titular shallow grave. His influence wins. But David draws the short straw for the grisly job of removing all forms of identification from the body. This is the turning point in the film. For David, the money causes self-disintegration. Descending from dull to delusional to dangerous, Boyle highlights David's transformation and derangement in the second and third acts. It is not really money that is the cause. It is the sin that is inherent in him, and all of us, that rises with the temptation of the money.

For David, the money causes self-disintegration. Descending from dull to delusional to dangerous, Boyle highlights David's transformation and derangement in the second and third acts. It is not really money that is the cause. It is the sin that is inherent in him, and all of us, that rises with the temptation of the money.