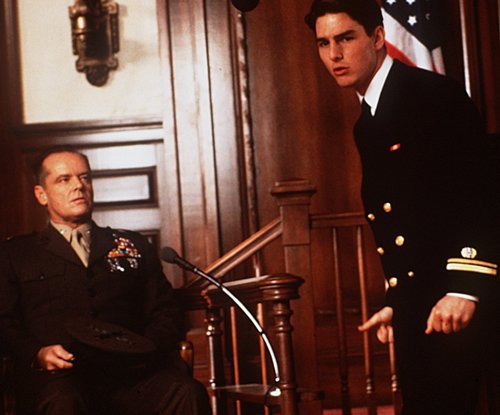

Director: Rob Reiner, 1992.

A Few Good Men opens with a choreographed sequence showing a Marine drill team in full dress uniform. Twirling rifles like batons, their synchronized moves underscore their training. More than this, it shows them as a unit, a machine with one goal: to bring honor to the Marine Corps. Honor is one of the themes of this Oscar-nominated drama.

When a Marine Private dies at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, two fellow marines are accused of murder. To provide defense in their courtmartial, Lt. Daniel Kaffee (Tom Cruise) is assigned as lead counsel. His approach is to plea bargain, regardless of right or wrong, innocence or guilt. He does not want a trial. His two co-counsels represent two sides to the same coin. Lt. Sam Weinberg (Kevin Pollack) sees clear guilt in their two defendants and pushes the plea, while Lt. Cdr. JoAnne Galloway (Demi Moore) smells a rat and wants to investigate more fully. Naive as a lawyer, she still believes in fairness and truth, and wants to give the two marines the best defense possible, not a simple plea bargain.

When the three lawyers go visit Gitmo to see the crime scene for themselves, they come face to face with their adversary, Col. Nathan Jessep (Jack Nicholson). Jessop is a career marine with delusions of grandeur. He, too, has two sidekicks who act as foils to his character and values. The use of foils in this movie has been explored by lawyer Ryan Blue, focusing on the two sub-characters on each side of the legal divide. Reiner uses them effectively to move the narrative to its conclusion.

When the three lawyers go visit Gitmo to see the crime scene for themselves, they come face to face with their adversary, Col. Nathan Jessep (Jack Nicholson). Jessop is a career marine with delusions of grandeur. He, too, has two sidekicks who act as foils to his character and values. The use of foils in this movie has been explored by lawyer Ryan Blue, focusing on the two sub-characters on each side of the legal divide. Reiner uses them effectively to move the narrative to its conclusion.Galloway, underwhelmed by Kaffee's investigation in Cuba and disappointed by his lack of passion, regales him for his lack of courage and conviction. She sees the lack of fairness in the inevitable plea bargain that Kaffee desires, for his own gain not theirs. But it is she who finally wakes him up to the truth.

Fairness is never really at the center of a legal trial. Justice will be done, but not necessarily resulting in fairness. The law does not always ensure that the guilty are pubished and the innocent walk free. As the movie moves toward a climax in the courtroom, Kaffee points out, "This is a sales pitch. It's not going to be won by the law, it's going to be won by the lawyers." It's all a game of posturing, showmanship and storytelling. The lawyers, him included, are paid to create a story that is believable by the jury. With the facts as the bones of its skeleton, their words create the flesh to hang on these bones. The side with the most believable story usually wins. Is this fair? Perhaps, perhaps not. It simply is. The legal system is more concerned with prosecutions and acquittals than with justice.

Getting back to honor and the Marine Corps, A Few Good Men uses the Marine Corps Code of Honor as a thread that keeps the story bound in place. The three core values of this code are commitment, courage and honor. One Marine says of the deceased, "he is dead because he had no honor." Kaffee tells one of the defendants, "You don't need a patch on your arm to have honor." Honor is clearly central to the plot.

This begs the questions, what is honor and how do we get it? Honor involves basic respect: for self, for others, for the unit, for the team. More than this, it connotes honesty and integrity. Honor comes to a person in many ways, through fame, success, distinction in a specific field. But all require the person to be worthy of honor, and this means doing right, maintaining a high standard of moral and ethical behavior. In short, having a high character. This is totally consistent with the biblical commands to live an upright life (Prov. 16:17), walking in the path of right and avoiding sin (Psa. 1:1-3). We attain honor by being honorable. Most Marines earn this through their skill, their strength, and their devotion to duty and to their code.

The code required unquestioning commitment and obedience to orders. That becomes the crux of the legal matter. When questioned on the stand, Lt. Kendrick (Kiefer Sutherland), one of Jessop's officers, says: "I have two books at my bedside, Lieutenant, the Marine Corps Code of Conduct and the King James Bible. The only proper authorities I am aware of are my commanding office Colonel Nathan R. Jessup and the Lord our God." But what happens when they conflict?

Kendrick seems to put Jessup on a par with Jesus. But when the laws of man run counter to the laws of God, God must win. In the early days of the church, the Apostles faced a similar situation, when their authority, the Jewish Sanhedrin, commanded them to stop preaching in the name of Jesus (Ac. 4:18). But rather than submitting to the will of these leaders, they obeyed the will of God. Yet, they did so knowingly and faced the painful consequences of this civil disobedience (Ac 5:40). While Kendrick obeyed Jessup, in like circumstances Christians must obey Jesus. As Peter said, "We must obey God rather than men!" (Ac 5:29)

Kendrick seems to put Jessup on a par with Jesus. But when the laws of man run counter to the laws of God, God must win. In the early days of the church, the Apostles faced a similar situation, when their authority, the Jewish Sanhedrin, commanded them to stop preaching in the name of Jesus (Ac. 4:18). But rather than submitting to the will of these leaders, they obeyed the will of God. Yet, they did so knowingly and faced the painful consequences of this civil disobedience (Ac 5:40). While Kendrick obeyed Jessup, in like circumstances Christians must obey Jesus. As Peter said, "We must obey God rather than men!" (Ac 5:29)What makes A Few Good Men so good is its dramatic climax. Reiner (The Princess Bride, The Bucket List) pits Cruise against Nicholson in its pivotal scene. The success of Kaffee's defense (and the success of Reiner's film) stands on this powerful interchange. Though Cruise has somewhat cruised through the film playing a typical Cruise character (think Maverick in Top Gun), he rises to the occasion for this confrontation which leads to the notorious declaration, "You can't handle the truth!"

Truth is the final and climactic theme of the film. Ryan Blue, in his blog article, points out that Kaffee's "two foils are used to personify Kaffee's dilemma: will he have the courage to pursue the truth or not?" Truth is powerful. Jesus, in his defense in front of Pilate, the judge who could save his life, said: "In fact, for this reason I was born, and for this I came into the world, to testify to the truth. Everyone on the side of truth listens to me" (Jn. 18:37). Earlier in his ministry, Jesus said, "The truth will set you free" (Jn. 8:32). What is that truth? Jesus is that very truth: "I am the way, the life and the truth" (Jn. 14:6).

Truth is the final and climactic theme of the film. Ryan Blue, in his blog article, points out that Kaffee's "two foils are used to personify Kaffee's dilemma: will he have the courage to pursue the truth or not?" Truth is powerful. Jesus, in his defense in front of Pilate, the judge who could save his life, said: "In fact, for this reason I was born, and for this I came into the world, to testify to the truth. Everyone on the side of truth listens to me" (Jn. 18:37). Earlier in his ministry, Jesus said, "The truth will set you free" (Jn. 8:32). What is that truth? Jesus is that very truth: "I am the way, the life and the truth" (Jn. 14:6).Will we be like Kaffee? Will we have the courage to pursue the truth? Will we have the courage to accept the truth and do what is right? Jesus is looking for a few good men!

Copyright ©2009, Martin Baggs

Having learned from our

Having learned from our

Archer's slow understanding of Welland as a clueless socialite causes him to look at the only free-bird in his social circle, Olenska. As he does so, he comes to realize they are a match for one another. But his engagement to Welland and Olenska's marriage to the count prove to be barriers to their love. Unconsummated, his love is not unrequited. Sadly it remains unfulfilled.

Archer's slow understanding of Welland as a clueless socialite causes him to look at the only free-bird in his social circle, Olenska. As he does so, he comes to realize they are a match for one another. But his engagement to Welland and Olenska's marriage to the count prove to be barriers to their love. Unconsummated, his love is not unrequited. Sadly it remains unfulfilled. One of the key themes of The Age of Innocence is the maze of social customs and norms that permeate a culture. As Ellen Olenska says to Archer, "Is New York such a labyrinth? I thought it was all straight up and down like Fifth Avenue. All the cross streets numbered and big honest labels on everything." Archer retorts, "Everything is labeled, but everybody is not." Olenska wanted a simple road map, all in plain sight. But high society is not like that. It is a jungle, a civilized one, but one that is uncharted.

One of the key themes of The Age of Innocence is the maze of social customs and norms that permeate a culture. As Ellen Olenska says to Archer, "Is New York such a labyrinth? I thought it was all straight up and down like Fifth Avenue. All the cross streets numbered and big honest labels on everything." Archer retorts, "Everything is labeled, but everybody is not." Olenska wanted a simple road map, all in plain sight. But high society is not like that. It is a jungle, a civilized one, but one that is uncharted. As Archer treads deeper in his plot of emotional treachery, he tries to persuade Olenska to somehow be with him. But she understands that even with their liberated approach, this could not be. "How can we be happy behind the backs of people who trust us?" The price for their love would be the unhappiness of their friends and relatives. That is too high a price. There are some social customs and norms that even Olenska was willing to accept. Likewise, Jesus was not an anarchist. He did follow Jewish tradition. He obeyed the law (Matt. 8:2-4). He worshipped in the synagogue (Lk. 4:14-20). He prayed to his father (Mk. 1:35). As we live within our social situations we must conform to some of its norms and expectations lest we become a malcontent, an insurrectionist, a rebel. Jesus was a counter-revolutionary, but not a rebel.

As Archer treads deeper in his plot of emotional treachery, he tries to persuade Olenska to somehow be with him. But she understands that even with their liberated approach, this could not be. "How can we be happy behind the backs of people who trust us?" The price for their love would be the unhappiness of their friends and relatives. That is too high a price. There are some social customs and norms that even Olenska was willing to accept. Likewise, Jesus was not an anarchist. He did follow Jewish tradition. He obeyed the law (Matt. 8:2-4). He worshipped in the synagogue (Lk. 4:14-20). He prayed to his father (Mk. 1:35). As we live within our social situations we must conform to some of its norms and expectations lest we become a malcontent, an insurrectionist, a rebel. Jesus was a counter-revolutionary, but not a rebel.

As Pepa begins her search for him, she runs into a number of eccentric characters: Paulina (Kiti Manver), a feminist lawyer and Ivan's new lover; Lucia (Julieta Serrano), Ivan's wigged-out and bewigged ex-wife; Candela (Maria Barranco), a brainless model; Carlos (Antonio Banderas), Ivan's son; and Marisa (Rossy de Palma), Carlos' fiancee. Impossibly unlikely scenarios bring laughs to this comedy: a terrorist skyjacking plot, a barbiturate-spiked gazpacho drink, a burned bed, and windows broken by tossed telephones. Then there is the elegantly coiffed but overly emotional cab driver who finds himself repeatedly in Hollywood-like chase scenes. You can't help but find something to laugh about even if the story is somewhat disjointed.

As Pepa begins her search for him, she runs into a number of eccentric characters: Paulina (Kiti Manver), a feminist lawyer and Ivan's new lover; Lucia (Julieta Serrano), Ivan's wigged-out and bewigged ex-wife; Candela (Maria Barranco), a brainless model; Carlos (Antonio Banderas), Ivan's son; and Marisa (Rossy de Palma), Carlos' fiancee. Impossibly unlikely scenarios bring laughs to this comedy: a terrorist skyjacking plot, a barbiturate-spiked gazpacho drink, a burned bed, and windows broken by tossed telephones. Then there is the elegantly coiffed but overly emotional cab driver who finds himself repeatedly in Hollywood-like chase scenes. You can't help but find something to laugh about even if the story is somewhat disjointed. Like most of Almodovar's films (

Like most of Almodovar's films ( If the women are clueless and victims of the men's infidelities, the men in this movie are weak. Not weak in Paul's sense, but weak in character. In particular, Ivan, whose infidelities are central to the main plot, is told by Paulina his latest lover, "You're weak, Ivan." He doesn't argue, he simply agrees, "Yes, sweetheart." He knows who and what he is.

If the women are clueless and victims of the men's infidelities, the men in this movie are weak. Not weak in Paul's sense, but weak in character. In particular, Ivan, whose infidelities are central to the main plot, is told by Paulina his latest lover, "You're weak, Ivan." He doesn't argue, he simply agrees, "Yes, sweetheart." He knows who and what he is.

Wings of the Dove raises the question of the priority of economic security or love. Would we sacrifice true love if it meant we could live a secure life of comfort? Would we marry someone we did not love for this purpose? Love is a precious thing, more valuable than simple creature comforts. Life is a fleeting thing, a mist that disappears (Jas. 4:14). So, to find love is to find a pearl of great value. Casting this aside for physical comfort is a sad indictment of a warped value system.

Wings of the Dove raises the question of the priority of economic security or love. Would we sacrifice true love if it meant we could live a secure life of comfort? Would we marry someone we did not love for this purpose? Love is a precious thing, more valuable than simple creature comforts. Life is a fleeting thing, a mist that disappears (Jas. 4:14). So, to find love is to find a pearl of great value. Casting this aside for physical comfort is a sad indictment of a warped value system. ys Kate as calculating and manipulative. She is a selfish lover who is at once both jealous and Machiavellian. One character says of her, "there's something going on behind those beautiful lashes." And there is, but we cannot be sympathetic to her, as she connives against friends who care for her. With Millie bearing a secret, she is an innocent who we root for, not Kate. And Roache seems miscast as Merton. He is not handsome enough to be credible as the love interest for multiple women. He does fill the role.

ys Kate as calculating and manipulative. She is a selfish lover who is at once both jealous and Machiavellian. One character says of her, "there's something going on behind those beautiful lashes." And there is, but we cannot be sympathetic to her, as she connives against friends who care for her. With Millie bearing a secret, she is an innocent who we root for, not Kate. And Roache seems miscast as Merton. He is not handsome enough to be credible as the love interest for multiple women. He does fill the role. Merton's hypocrisy plays itself out. Hypocrisy is the pretense of having a virtuous character, in this case to be in love with someone you're not in love with. It comes from the Greek root to act in a play, to pretend. It is not a positive quality. Whenever we consider faking it, whether in love or in other situations, we must realize we are lying. The New Testament exhorts us to avoid lying (Col. 3:9). Indeed, one of the Ten Commandments says, "You shall not give false testimony against your neighbor" (Exod. 20:16). For reasons good or ill, it is a slippery slope that will pull us down to a dismal end.

Merton's hypocrisy plays itself out. Hypocrisy is the pretense of having a virtuous character, in this case to be in love with someone you're not in love with. It comes from the Greek root to act in a play, to pretend. It is not a positive quality. Whenever we consider faking it, whether in love or in other situations, we must realize we are lying. The New Testament exhorts us to avoid lying (Col. 3:9). Indeed, one of the Ten Commandments says, "You shall not give false testimony against your neighbor" (Exod. 20:16). For reasons good or ill, it is a slippery slope that will pull us down to a dismal end.

From an early flashback we realize that as a boy Samir witnessed his father being killed by a car bomb. There is clearly more to Samir than meets the eye. As a devout Moslem he fits in well with Omar and when they escape he becomes central to the cell group's mission to bring terror to mainland America. But is he merely a terrorist? Or is there something else?

From an early flashback we realize that as a boy Samir witnessed his father being killed by a car bomb. There is clearly more to Samir than meets the eye. As a devout Moslem he fits in well with Omar and when they escape he becomes central to the cell group's mission to bring terror to mainland America. But is he merely a terrorist? Or is there something else?

In one scene, a stressed and pursued Samir is talking with an American intelligence operative, who tells him, "This is war! You do what it takes to win." This is the same message that the terrorist preached to him earlier. Both sides see this as war. And both sides are willing to take matters into their own hands. How different are they are? Who are the good guys and who are the bad guys? Indeed, as a terrorist reminded Samir, "Once upon a time it was the Americans who were terrorists to the British." Black and white has mixed to form gray shades with dark shadows.

In one scene, a stressed and pursued Samir is talking with an American intelligence operative, who tells him, "This is war! You do what it takes to win." This is the same message that the terrorist preached to him earlier. Both sides see this as war. And both sides are willing to take matters into their own hands. How different are they are? Who are the good guys and who are the bad guys? Indeed, as a terrorist reminded Samir, "Once upon a time it was the Americans who were terrorists to the British." Black and white has mixed to form gray shades with dark shadows.

Sheridan could have milked this story for its sentimentality. But he refrains from doing so. Instead, he lets Daniel Day-Lewis lose himself in the main role as the adult Brown. He plays the man as a cantankerous yet brilliant artist who does not want sympathy. Rather, he wants to be treated as a person, a real human being. Lewis is so good in this role it seems he really has cerebral palsy, and he worthily won the Oscar for best actor, his first. (He was nominated for his outstanding role in

Sheridan could have milked this story for its sentimentality. But he refrains from doing so. Instead, he lets Daniel Day-Lewis lose himself in the main role as the adult Brown. He plays the man as a cantankerous yet brilliant artist who does not want sympathy. Rather, he wants to be treated as a person, a real human being. Lewis is so good in this role it seems he really has cerebral palsy, and he worthily won the Oscar for best actor, his first. (He was nominated for his outstanding role in  Once we can communicate with others, a deeper need is to be able to express our unique creativity. We have all been made in the image of our creative creator (Gen. 1:26). Part of this image is the ability to create. Art is one form. Christy had that gift. For years he must have felt a yearning to express himself through this artistic outlet, yet was unable to do so. Once he could communicate he was given the tools necessary to paint: brushes, canvas, paints, etc. And he made contributions to the world that others, with the use of all their limbs, could not match. He even painstakingly wrote his own autobiography, typing it a letter at a time with the toes of his left foot, offering hope to many!

Once we can communicate with others, a deeper need is to be able to express our unique creativity. We have all been made in the image of our creative creator (Gen. 1:26). Part of this image is the ability to create. Art is one form. Christy had that gift. For years he must have felt a yearning to express himself through this artistic outlet, yet was unable to do so. Once he could communicate he was given the tools necessary to paint: brushes, canvas, paints, etc. And he made contributions to the world that others, with the use of all their limbs, could not match. He even painstakingly wrote his own autobiography, typing it a letter at a time with the toes of his left foot, offering hope to many!

We start with Kirk (Chris Pine) as a rebellious teenager in Iowa. One by one the rest of the crew of the Enterprise are brought center-stage. There are Uhura (Zoe Saldana), Sulu (John Cho), and Chekov (Anton Yelchin). Of course Doctor "Bones" McCoy (Karl Urban) is an early and close buddy of Kirk's, who helps him get onto the USS Enterprise when he is supposed to be grounded. And there's Scotty (Simon Pegg,

We start with Kirk (Chris Pine) as a rebellious teenager in Iowa. One by one the rest of the crew of the Enterprise are brought center-stage. There are Uhura (Zoe Saldana), Sulu (John Cho), and Chekov (Anton Yelchin). Of course Doctor "Bones" McCoy (Karl Urban) is an early and close buddy of Kirk's, who helps him get onto the USS Enterprise when he is supposed to be grounded. And there's Scotty (Simon Pegg,  Although Star Trek is mostly flash and fun, without much depth, there are one or two nuggets. This is the first -- friendship. Initially Kirk despises Spock, who has accused him of cheating on a key test. But Kirk moves beyond this. He does not allow this incident to define the relationship. Likewise, we too may find our best friendships emerging in the strangest circumstances. Friendship is one of life's greatest joys. To have a true friend is to have a treasure from heaven. The Bible tells us "a friend loves at all times" (Prov. 17:17). Even a person who seems to be a thorn in our side may be destined to become an intimate pal. We just need to be willing to be open to any possibilities that God has for us.

Although Star Trek is mostly flash and fun, without much depth, there are one or two nuggets. This is the first -- friendship. Initially Kirk despises Spock, who has accused him of cheating on a key test. But Kirk moves beyond this. He does not allow this incident to define the relationship. Likewise, we too may find our best friendships emerging in the strangest circumstances. Friendship is one of life's greatest joys. To have a true friend is to have a treasure from heaven. The Bible tells us "a friend loves at all times" (Prov. 17:17). Even a person who seems to be a thorn in our side may be destined to become an intimate pal. We just need to be willing to be open to any possibilities that God has for us. When Vulcan faces the evil plans of Nero, the federation is called into action, manning the Enterprise with all the cadets at hand. The main plot line, then, is the race to thwart Nero, who determines to destroy planet after planet in his vengeance-fueled fury, while secondarily bringing all these characters into their position for subsequent adventures. Abrams pulls it off well.

When Vulcan faces the evil plans of Nero, the federation is called into action, manning the Enterprise with all the cadets at hand. The main plot line, then, is the race to thwart Nero, who determines to destroy planet after planet in his vengeance-fueled fury, while secondarily bringing all these characters into their position for subsequent adventures. Abrams pulls it off well.

During the movie, Said and Khaled offer perspectives on what has led them to this point. "Life here is like life imprisonment. The crimes of the occupation are countless." The West Bank settlers have brought injustice and discrimination with them. "They use their war machine and their political and economical might to force us to accept their solution: that either we accept inferiority, or we will be killed." From their position, life under Israeli authority is unacceptable; they have little freedom. Khaled's philosophy, perhaps drummed into him by Jamal and his extreme Muslim fundamentalism, offers him only one solution: "If we can't live as equals, at least we'll die as equals." There is another perspective, a different solution to injustice, which emerges later.

During the movie, Said and Khaled offer perspectives on what has led them to this point. "Life here is like life imprisonment. The crimes of the occupation are countless." The West Bank settlers have brought injustice and discrimination with them. "They use their war machine and their political and economical might to force us to accept their solution: that either we accept inferiority, or we will be killed." From their position, life under Israeli authority is unacceptable; they have little freedom. Khaled's philosophy, perhaps drummed into him by Jamal and his extreme Muslim fundamentalism, offers him only one solution: "If we can't live as equals, at least we'll die as equals." There is another perspective, a different solution to injustice, which emerges later. Said and Khaled are shorn and shaved, ritually bathed to prepare them for their personal jihad: to blow up themselves and as many Israeli soldiers as possible. As they allow the explosives to be strapped to their chests, they offer a study in contrasts. One is confident in his Islamic faith. He is ready to martyr himself and arrive in paradise now. The other is afraid. He is unsure. Is this what God (Allah) has decreed for him? The biggest contrast, though, is between the two soon-to-be martyrs and their handler, Jamal. His job is easy, to recruit, prepare, motivate, and send. There is no immediate personal sacrifice for him. He just needs to ensure his two recruits don't turn back.

Said and Khaled are shorn and shaved, ritually bathed to prepare them for their personal jihad: to blow up themselves and as many Israeli soldiers as possible. As they allow the explosives to be strapped to their chests, they offer a study in contrasts. One is confident in his Islamic faith. He is ready to martyr himself and arrive in paradise now. The other is afraid. He is unsure. Is this what God (Allah) has decreed for him? The biggest contrast, though, is between the two soon-to-be martyrs and their handler, Jamal. His job is easy, to recruit, prepare, motivate, and send. There is no immediate personal sacrifice for him. He just needs to ensure his two recruits don't turn back. The third person central to the film is Suha (Lubna Azabal). She is the daughter of a martyr and acquaintance to both Said and Khaled. When the operation becomes compromised and she learns of their plans, she seizes the opportunity to persuade them to give up the mission. She is the foil that allows us to see the other perspective. Her scenes become crucial to making this a balanced and fair film.

The third person central to the film is Suha (Lubna Azabal). She is the daughter of a martyr and acquaintance to both Said and Khaled. When the operation becomes compromised and she learns of their plans, she seizes the opportunity to persuade them to give up the mission. She is the foil that allows us to see the other perspective. Her scenes become crucial to making this a balanced and fair film. t be so naive. There can be no freedom without struggle. As long as there is injustice, someone must make a sacrifice." Suha responds, "That's no sacrifice. That's revenge. If you kill, there's no difference between victim and occupier." This highlights the other response to injustice -- sacrifice. Although Khaled's form of sacrifice is to kill others, there is a sacrifice that has already dealt with injustice: Jesus' sacrifice. He willingly allowed himself to be executed on the cross (Lk. 23:26-49). He did so, to absorb the punishment for sin, all the sins of the world (Rom. 3:23-26). His sacrifice came with the gift of forgiveness and life (Col. 1:14), not death.

t be so naive. There can be no freedom without struggle. As long as there is injustice, someone must make a sacrifice." Suha responds, "That's no sacrifice. That's revenge. If you kill, there's no difference between victim and occupier." This highlights the other response to injustice -- sacrifice. Although Khaled's form of sacrifice is to kill others, there is a sacrifice that has already dealt with injustice: Jesus' sacrifice. He willingly allowed himself to be executed on the cross (Lk. 23:26-49). He did so, to absorb the punishment for sin, all the sins of the world (Rom. 3:23-26). His sacrifice came with the gift of forgiveness and life (Col. 1:14), not death.

The opening scenes depict Buddy as a fish-out-of-water, being a giant "elf" trying to fit into an elf's world. Clothes, furniture, even houses are difficult for him. Hardest of all is his job making etch-a-sketch toys. He simply cannot cut the pace of a true toy-making elf. He does not fit in. When he overhears one elf telling another that he is actually a human, it crushes him. "Why the long face, Buddy?" says Leon the Snowman. "It seems I'm not an elf," replies the sad Buddy. "Of course you're not an elf. You're six-foot-three and had a beard since you were fifteen." Buddy was the only one who didn't know he was no elf.

The opening scenes depict Buddy as a fish-out-of-water, being a giant "elf" trying to fit into an elf's world. Clothes, furniture, even houses are difficult for him. Hardest of all is his job making etch-a-sketch toys. He simply cannot cut the pace of a true toy-making elf. He does not fit in. When he overhears one elf telling another that he is actually a human, it crushes him. "Why the long face, Buddy?" says Leon the Snowman. "It seems I'm not an elf," replies the sad Buddy. "Of course you're not an elf. You're six-foot-three and had a beard since you were fifteen." Buddy was the only one who didn't know he was no elf.  Of course, if Buddy is a stand-out outcast at the north pole, he is just as much out of his element in the real world. Still dressed in elf clothes, Walter thinks he is a Christmas-gram. Others mistake him for a seasonal worker, one of Santa's elves working in Gimbals, the huge toy store. It is there that he meets Jovie (Zooey Deschanel), another "elf" and discovers that warmth in his face might be love in his heart.

Of course, if Buddy is a stand-out outcast at the north pole, he is just as much out of his element in the real world. Still dressed in elf clothes, Walter thinks he is a Christmas-gram. Others mistake him for a seasonal worker, one of Santa's elves working in Gimbals, the huge toy store. It is there that he meets Jovie (Zooey Deschanel), another "elf" and discovers that warmth in his face might be love in his heart. His naivete presents a lesson for all of us. He accepts everyone. In his childlike (elf-like?) innocence, he simply cannot compute cynicism, sarcasm or even criminality. He is warm-hearted and kind to both family and strangers, those he knows and those he does not. In doing so, he enables Walter to see what is most important to him, and find his own heart.

His naivete presents a lesson for all of us. He accepts everyone. In his childlike (elf-like?) innocence, he simply cannot compute cynicism, sarcasm or even criminality. He is warm-hearted and kind to both family and strangers, those he knows and those he does not. In doing so, he enables Walter to see what is most important to him, and find his own heart.