Director: Oliver Stone, 1991 (R)

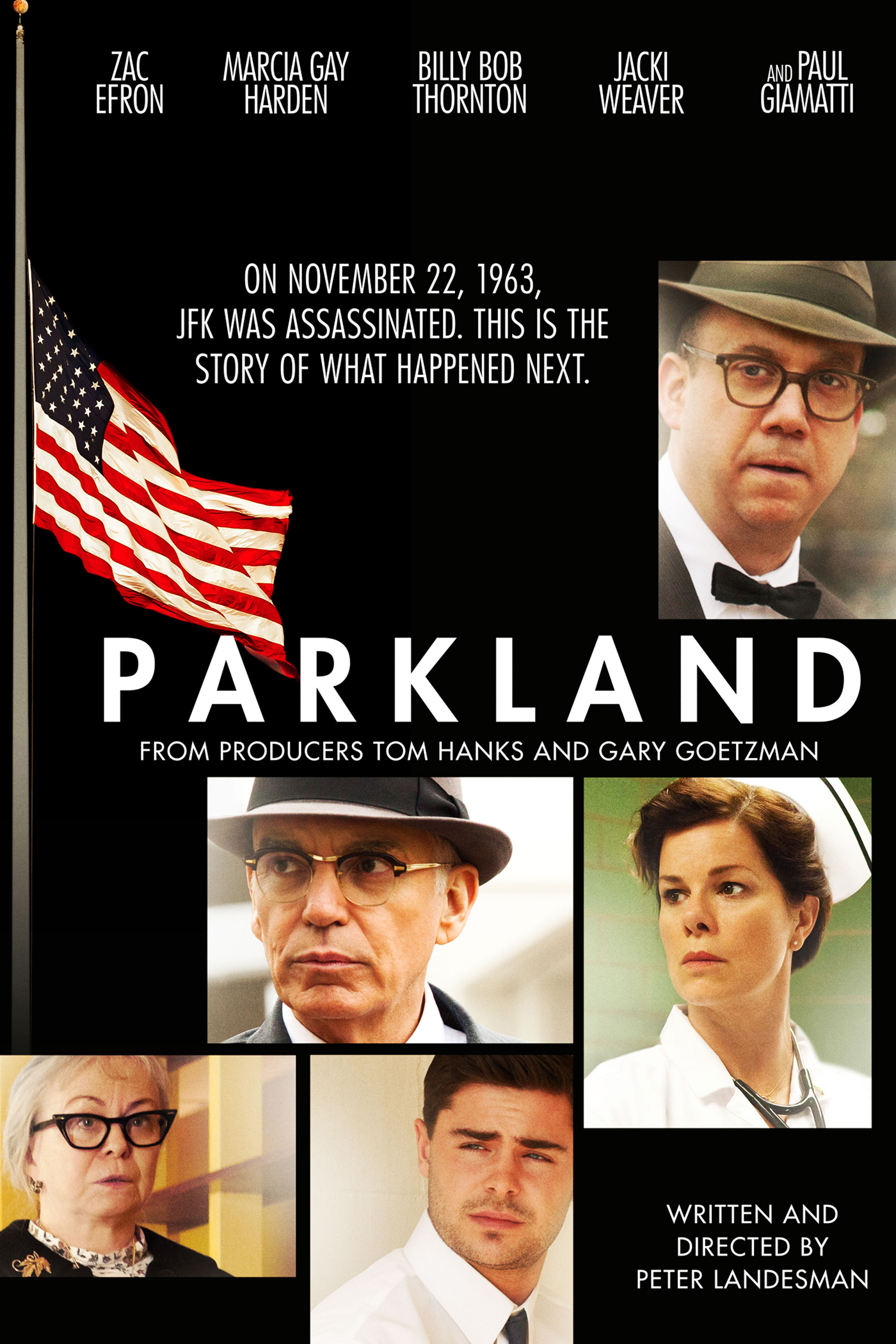

2013 marks the 50th anniversary of the Kennedy

assassination. On November 22, 1963 President John F. Kennedy was shot in

Dallas during a motorcade. The fourth president of the USA assassinated, he was

the first lost on the watch of the Secret Service. His death changed the nation

and the nation’s politics. Even a half

century later, the interest in Kennedy’s death persists, undaunted. This is

evident from the clutch of new books issued in remembrance of this event,

including Jesse Ventura’s “They Killed our President” and Jerry Kroth’s “Coup

D’Etat” as well as the new movie Parkland.

More than ever, the mystery surrounding Kennedy’s death polarizes along the

lone gunman/multiple gunmen conspiracy spectrum.

Oliver Stone’s JFK may be his magnum opus. An epic in itself,

the director’s cut runs almost 3 ½ hours. But the 200 minutes are captivating,

not just due to the Oscar-winning editing and cinematography. Neither is it due

to the superb cast of Hollywood A-listers, including Kevin Costner, Tommy Lee

Jones (nominated for an Oscar here), Gary Oldman, Edward Asner, Jack Lemmon,

Walter Matthau, Ed Asner, Kevin Bacon, Joe Pesci, Donald Sutherland and Sissy

Spacek. Rather, through the use of flashback and interspersing of historic

footage, Stone brings a profound sense of conspiracy and mystery unfolding. It

leaves the viewer eager to learn more, to do subsequent research in the

literature. I certainly felt that way.

The movie begins with sound-bites from President

Eisenhower’s Farewell Address to the nation in January 1961: “We must guard

against the acquisition of unwarranted influence – whether sought or unsought –

by the military-industrial complex. We must never let the weight of this

combination endanger our liberties or democratic processes.” This, and the

title cards, set the context for the film, and the second half of the movie

sheds light on this.

The film focuses on New Orleans District Attorney Jim

Garrison (Kevin Costner). Like many other Americans, he hears about the

assassination from television news accounts. But it is only three years later

that he begins to question that government’s account of the death at the hands

of lone-gunman Lee Harvey Oswald (Gary Oldman). Since Oswald used to live in

New Orleans and had involvement with various anti-Castro organizations in his

city, he begins to investigate Oswald. With his team of assistant Das and

investigators, the search begins to uncover facts that dispute the government’s

account.

While Oswald is the center of the inquiry, it is not long

before Clay Shaw (Tommy Lee Jones), businessman and closet homosexual, comes

into the crosshairs, brought their by David Ferrie (Joe Pesci).

Little by little, other agencies seem to be

involved, from the CIA to the FBI as well as Naval Intelligence and the mob.

The screenplay (written in part by Stone) is based on

Garrison’s own book, “On the Trail of the Assassins.” And Garrison comes across

as a man on a mission, even if it is at the expense of his wife (Sissy Spacek)

and family. Once the JFK bug bites him, he cannot let it go. Weaving through

the dense web of lies and deceit, it is not until he travels to Washington DC

to meet mystery man X (Donald Sutherland, actually playing Fletcher Prouty, a

Colonel in Military Intelligence) that Garrison begins to understand the depths

of conspiracy he finds himself in. X tells him: “Fundamentally, people are

suckers for the truth. And the truth is on your side, Bubba.” Garrison comments

later, “Telling the truth can be a very scary thing sometimes.” He wants to

find the truth, and the American people are behind him, even if his government

is not.

People want to find truth. Lives cannot be built on lies.

Truth is found in Jesus Christ, “who came from the Father, full of grace and

truth” (Jn. 1:14). When we know the truth we can live in the light of truth

(Jn. 3:21). Then and only then do we find ourselves free (Jn. 8:32). Although

the enemy seeks to deceive, as the father of lies (Jn. 8:44), God shines his

light of truth on us; he wants us to cut away through Satan’s conspiracies.

X, though he only appears in one extended scene, helps

Garrison understand the motive behind Kennedy’s murder: “The organizing

principle of any society, Mr. Garrison, is for war. The authority of the state

over its people resides in its war powers. Kennedy wanted to end the Cold War

in his second term.” Garrison echoes this, “The war is the biggest business in

America, worth $80 billion a year.” This ties back to the comments from

Eisenhower at the start.

Stone’s movie hence ties the murder to the military-industrial

complex. And we see backroom meetings of key military leaders. Beyond this,

Stone posits that Lyndon Johnson, Kennedy’s Vice President, is involved,

extending the conspiracy to the highest levels of government. With his

ascendancy to the presidency, he reversed policy and moved to continue the Viet

Nam War, despite its cost in lives and dollars. Bombs and bullets brought

profit to the corporations supporting the military.

In contrast, biblically the organizing principle of God’s

society is peace. He sent his son to earth as the Prince of Peace (Isa. 9:6).

Though this first advent did not solve the world’s problems of wars, Jesus

offered internal peace and peace with God (Rom. 5:1). But after his second

advent and into eternity, there will be true peace in society. As Isaiah

prophecies, “They will beat their swords into plowshares and their spears into

pruning hooks. Nation will not take up sword against nation, nor will they

train for war anymore.” (Isa. 2:4)

It is in the latter stages, when Garrison takes Shaw to

trial, the only trial ever brought in relation to the Kennedy assassination,

that the movie presents indisputable evidence of conspiracy. In the best scene

of the film, Garrison comments on the so-called magic bullet:

The Warren Commission thought they

had an open-and-shut case. Three bullets, one assassin. But two unpredictable

things happened that day that made it virtually impossible. One, the

eight-millimeter home movie taken by Abraham Zapruder while standing by the

grassy knoll. Two, the third wounded man, James Tague, who was knicked by a

fragment, standing near the triple underpass. The time frame, five point six

seconds, determined by the Zapruder film, left no possibility of a fourth shot.

So the shot or fragment that left a superficial wound on Tague's cheek had to

come from the three shots fired from the sixth floor depository. That leaves

just two bullets. And we know one of them was the fatal head shot that killed

Kennedy. So now a single bullet remains. A single bullet now has to account for

the remaining seven wounds in Kennedy and Connelly. But rather than admit to a

conspiracy or investigate further, the Warren Commission chose to endorse the

theory put forth by an ambitious junior counselor, Arlen Spector, one of the

grossest lies ever forced on the American people. We've come to know it as the

"Magic Bullet Theory." This single-bullet explanation is the

foundation of the Warren Commission's claim of a lone assassin. Once you

conclude the magic bullet could not create all seven of those wounds, you'd

have to conclude that there was a fourth shot and a second rifle. And if there

was a second rifleman, then by definition, there had to be a conspiracy.

With this conspiracy supported, the question is who was

involved. Garrison argues that it had to reach to the highest levels and so

concludes that this was in fact a coup d’etat.

Even though the Warren Commission, led by Chief Justice

Warren, concluded that the assassination was the result of Oswald acting alone,

and that Jack Ruby (Oswald’s killer days later) acted alone, there is simply

too many unlikely coincidences for this to be likely. Witnesses killed in the

most suspicious circumstances. Autopsy results that simply don’t match the

evidence from the Dallas Parkland doctors who attended Kennedy’s death. The

killing bullet that entered from the front, despite Oswald firing from behind

Kennedy. The magic bullet that has to explain so many wounds that it has to

defy the laws of physics. Former Governer Ventura does a fine job of collecting

sufficient evidence to provide more than reasonable doubt of Oswald’s guilt.

Indeed, in contrast to the Warren Commision’s report, the US House of

Representatives Select Committee on Assassinations, established in 1976,

concluded that Kennedy’s death was the result of a conspiracy, although it did

not determine who exactly was involved.

Late in the film Garrison, frustrated with the thwarting of

his mission, declares to the press: “Let justice be done though the heavens

fail.” In the JFK murder, justice has not been done. The American people

deserve better. But Stone and Ventura and Kroth and many others have at least

opened the curtain on the great deception and conspiracy that has plagued the

country for 5 decades. Oswald could not have acted alone. He may not even have

been the shooter. His guilt, never proven in a court of law, may never be

undone. We may never know the real truth. And justice will surely never be

done.

Copyright ©2013, Martin Baggs