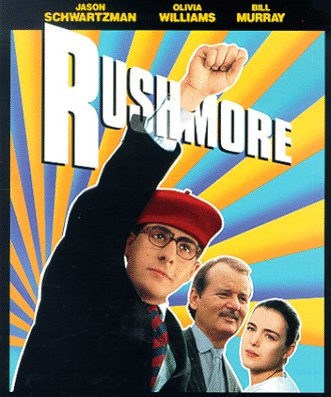

Director: Wes Anderson, 1998. (R)

After the success of his debut film, indie classic Bottle Rocket, writer-director Anderson (The Darjeeling Limited) turned his attention away from crime and onto something we have all experienced: high school. Like his earlier film, he focuses on quirky characters and dry humor, but in a tighter script.

Rushmore centers on three characters: Max Fischer (Jason Schwartzman), Herman Blume (Bill Murray), and Rosemary Cross (Olivia Williams). Max is a precocious 15 year-old student at the prestigious and expensive prep school, Rushmore Academy. Academically challenged, Max faces the threat of expulsion because he spends all his time leading clubs and societies. He is the king of extracurricular activities, and apparently mature beyond his age. Harvey, on the other hand, is a successful businessman with two rebellious sons at the school. He has been through all this and made his millions but lost his purpose and meaning. Though they form a friendship, they ultimately become rivals for the love of Rosemary, an elementary teacher at the school. This odd love triangle brings the conflict that propels the story.

Rushmore centers on three characters: Max Fischer (Jason Schwartzman), Herman Blume (Bill Murray), and Rosemary Cross (Olivia Williams). Max is a precocious 15 year-old student at the prestigious and expensive prep school, Rushmore Academy. Academically challenged, Max faces the threat of expulsion because he spends all his time leading clubs and societies. He is the king of extracurricular activities, and apparently mature beyond his age. Harvey, on the other hand, is a successful businessman with two rebellious sons at the school. He has been through all this and made his millions but lost his purpose and meaning. Though they form a friendship, they ultimately become rivals for the love of Rosemary, an elementary teacher at the school. This odd love triangle brings the conflict that propels the story.Shooting his old high school, St. Johns School in Houston as Rushmore, Anderson uses these three characters to offer different perspectives on life and success. Herman shares his philosophy in an assembly address to the faculty and students:

You guys have it real easy. I never had it like this where I grew up. But I send my kids here because the fact is you go to one of the best schools in the country: Rushmore. Now, for some of you it doesn't matter. You were born rich and you're going to stay rich. But here's my advice to the rest of you: Take dead aim on the rich boys. Get them in the cross hairs and take them down. Just remember, they can buy anything but they can't buy backbone. Don't let them forget it. Thank you.While the rest of the students sit bored, Max gives Herman a standing ovation.

Herman's cynical view of life focuses on a win-lose philosophy. There will be one winner and the rest come in second or worse. Such competitive approach decries collaboratism and service. Economic warfare is the name of his game. The pie is fixed, and our job is to get as much of it as possible, regardless of the consequence to others. This is not Jesus' approach. He modeled servant-leadership and a lifestyle of serving and giving (Mk. 9:35).

Herman's cynical view of life focuses on a win-lose philosophy. There will be one winner and the rest come in second or worse. Such competitive approach decries collaboratism and service. Economic warfare is the name of his game. The pie is fixed, and our job is to get as much of it as possible, regardless of the consequence to others. This is not Jesus' approach. He modeled servant-leadership and a lifestyle of serving and giving (Mk. 9:35). Though he is wrong about much of life, Herman is right in that money cannot buy backbone, or character. That is something that is developed through hard work and prayer. Moreover, you cannot buy grace, salvation or the supernatural powers from God. Simon the sorcerer tried this and was unsuccessful (Acts 8:18). All are offered freely by God and must be received by faith in this manner (Eph. 2:8-9).

If Herman's cynicism puts him at one of the spectrum, Max's idealism places him at the other. He seems to have it all figured out, even at his tender young age. When Herman asks him what his secret is, Max responds, "The secret, I don't know. . . . I guess you've just gotta find something you love to do and then . . . do it for the rest of your life. For me it's going to Rushmore."

Certainly, this conveys the enthusiasm of youth. Yet it captures the essence of truth. We all want to find something we love. If we do, then work feels like play and we have discovered our vocation, what we were meant to do. This communicates the idea of mission, whether in ministry or business. Jesus wants us to love him whole-heartedly (Mk. 12:30) and to follow him in his kingdom mission. When we find Jesus, when we realize our purpose, our soul feels settled and at peace (Phil. 4:7).

Between these two philosophies sits Rosemary. Younger than Herman, she is too old for Max's amorous intentions. (As mature as he thinks he is, he is just a child still.) She has experienced loss and has adopted a resigned view of life. She does not chase anything, but seems more accepting of what comes at her. But when it is both Herman and Max, she sees their love as youthful, even juvenile, telling Max, "You know, you and Herman deserve each other. Your'e both little children." Love can do that. It revitalizes. It sparks life into a cynical and cold heart. In this case it ignites friendly war that results in expulsion and competition. As Herman says, "She's my Rushmore."

Between these two philosophies sits Rosemary. Younger than Herman, she is too old for Max's amorous intentions. (As mature as he thinks he is, he is just a child still.) She has experienced loss and has adopted a resigned view of life. She does not chase anything, but seems more accepting of what comes at her. But when it is both Herman and Max, she sees their love as youthful, even juvenile, telling Max, "You know, you and Herman deserve each other. Your'e both little children." Love can do that. It revitalizes. It sparks life into a cynical and cold heart. In this case it ignites friendly war that results in expulsion and competition. As Herman says, "She's my Rushmore."Max's immaturity sees his time at Rushmore as lasting forever. It is his reason for living. Then he sees Rosemary and she becomes his reason for living. Neither are true; both are ephemeral illusions. School will not last forever. We were not designed to spend our lives in academia. And Max was not the right person for Rosemary, being both too young and a student at her school. Their relationship bordered on the unprofessional and unethical.

We can glean nuggets from each character, both positive and negative, to improve our own lives. We can spurn the cynicism of age that Herman presents. Instead, we can seek to retain some of the enthusiasm and youthful idealism like Max without becoming dewy-eyed dreamers seeing what is not there. And we can bring a sage acceptance of life and its calamities like Rosemary.

We can glean nuggets from each character, both positive and negative, to improve our own lives. We can spurn the cynicism of age that Herman presents. Instead, we can seek to retain some of the enthusiasm and youthful idealism like Max without becoming dewy-eyed dreamers seeing what is not there. And we can bring a sage acceptance of life and its calamities like Rosemary.Ultimately, Anderson forces us to face the question that Max and Herman answered, "What or who is my Rushmore?" If it is not Jesus, our reason for living is probably misplaced.

Copyright ©2010, Martin Baggs

No comments:

Post a Comment