Director: Matteo Garrone, 2009. (NR)

Gomorrah draws to mind the biblical account of Genesis 19 when "the LORD rained down burning sulfur on Sodom and Gomorrah" (v.24). The reason he did this was because "the outcry against Sodom and Gomorrah is so great and their sin so grievous" (Gen. 18:20). Moral darkness had descended upon the city. Similarly, moral darkness has fallen on Naples in this tough-to-watch award-winning Italian film.

The movie opens with the unexpected shooting of several unsuspecting gangsters as they are relaxing in a tanning salon. This is reminiscent of the shootings at the end of The Godfather. Indeed, Gomorrah offers an inside look at the mob underworld in Naples, as The Godfather did for the mafia in America. But where that movie focused on the godfather, Don Corleone and his son, in Gomorrah we never see the mob boss. Rather, the emphasis is on individual gangsters as well as the individuals who come into contact with the system. It is, in this respect, a portrayal of the grass-roots level impact of organized crime.

Garrone has based his movie on the best-selling non-fiction book by Robert Saviano which exposes the crime syndicate known as the "Camorra" or "System" and the rules it ruthlessly enforces. As a result of his book and this film, Saviano has received numerous death threats from the Camorra and has to live under police protection. Unlike the American Mafia or Sicilian Cosa Nostra, where there is a clear hierarchy, the Camorra is flatter and looser, with different clans vying for power.

The film pulls five individuals out of the book's narrative and, though unrelated, interweaves their stories together to highlight the impact of crime on the criminals and their families as well as the innocent. None are ranking members; all seem ordinary people with lives and dreams. Most are living in the urban ghetto.

Don Ciro is a middle-aged middleman who handles the money distribution to the families of imprisoned clan members. Timid, he shuns violence and simply wants to get out of the system. But the system won't let him. He cannot escape without making payment for his life. Toto is a 13-year-old grocery deliverer who aspires to be part of the clan. Through an accidental incident he is given a chance to be initiated into this violent life. Marco and Ciro are two older teens who are cocky gangster wannabes. Full of small-time plans, they think they are invincible. But they cross too many clan leaders who cannot tolerate their disrespect. Pasquale is a tailor who works for a garment factory owner with ties to the Camorra. When he begins consulting for a competing Chinese company, he crosses a line. The Camorra brooks no competition. And Roberto is a young graduate who starts working for a clan businessman, Franco, who illegally dumps toxic waste in disused quarries. All five find out to their dismay just how deeply the tentacles of this crime organization extend and the depths to which the Camorra will go to exact retribution.

Don Ciro is a middle-aged middleman who handles the money distribution to the families of imprisoned clan members. Timid, he shuns violence and simply wants to get out of the system. But the system won't let him. He cannot escape without making payment for his life. Toto is a 13-year-old grocery deliverer who aspires to be part of the clan. Through an accidental incident he is given a chance to be initiated into this violent life. Marco and Ciro are two older teens who are cocky gangster wannabes. Full of small-time plans, they think they are invincible. But they cross too many clan leaders who cannot tolerate their disrespect. Pasquale is a tailor who works for a garment factory owner with ties to the Camorra. When he begins consulting for a competing Chinese company, he crosses a line. The Camorra brooks no competition. And Roberto is a young graduate who starts working for a clan businessman, Franco, who illegally dumps toxic waste in disused quarries. All five find out to their dismay just how deeply the tentacles of this crime organization extend and the depths to which the Camorra will go to exact retribution.Retribution is an extended theme. Most of the five stories focus on this topic in one way or another. When the rules of the Camorra are broken, the gangsters seek retribution. Usually with a gun. It matters not the age or sex of the victim. What matters is exacting this retribution.

The idea of retribution focuses on meting out merited discipline, just punishment. It connotes swift revenge, a paying back for an evil done earlier. It flies in the face of Christianity. Followers of Jesus are not to take matters into our own hands like this. Paul tells us to leave vengeance to God (Rom. 12:19). But retribution in the legal sense appears in the biblical texts, particularly in the death of Jesus. Though he was innocent of any crime, and lived a life free of sin (1 Pet. 2:22), the punishment for the sin of others, for our sin, was poured out on him. He experienced the retribution of God that we rightfully should receive. In doing this, he absorbed in his death the wrath of God (Rom. 3:25).

The subplot of Roberto's introduction to illegal toxic waste management is particularly despicable. As Franco goes about seemingly helping save poor families, he is merely filling his pockets and the coffers of the Camorra while destroying the environment. Organized crime does not just focus on prostitution, drugs and gambling. Where there is "opportunity for profit" they are involved. Such schemes not only pollute the earth but damage people's health, as Roberto witnesses first hand.

The subplot of Roberto's introduction to illegal toxic waste management is particularly despicable. As Franco goes about seemingly helping save poor families, he is merely filling his pockets and the coffers of the Camorra while destroying the environment. Organized crime does not just focus on prostitution, drugs and gambling. Where there is "opportunity for profit" they are involved. Such schemes not only pollute the earth but damage people's health, as Roberto witnesses first hand.We are called to care for the earth (Gen. 1:26). We have been given a social stewardship. Though it is politically correct to focus on green initiatives these days, such emphasis stems from the Garden of Eden. God's beautiful creation is our playground. If we destroy it, we will all suffer, and we will leave a damning legacy for future generations.

The world of Gomorrah is gray; its pulse is cold and cruel. All five scenarios end with, or involve, violence and death. The landscape is bleak, mostly sleazy concrete apartments. Even when the film moves outside the city, the countryside is brown and barren, under heavy gray skies. Sunshine is missing. Color is absent. Beauty is gone. Drab and dull, life has been supplanted by death.

The core values of the Camorra and those living under its umbrella are clear: power, money, and blood. The people have little choice or freedom. There is no grace, no forgiveness, no hope. Gomorrah is a chilling picture of life apart from Christ. Without these life is meaningless and can be curtailed brutally with a swift bullet. In contrast, Jesus' gospel of grace offers forgiveness for sin (Matt. 26:28), instead of retributive justice, and hope for a future (Tit. 2:13). The way of redemption is superior to retribution!

The core values of the Camorra and those living under its umbrella are clear: power, money, and blood. The people have little choice or freedom. There is no grace, no forgiveness, no hope. Gomorrah is a chilling picture of life apart from Christ. Without these life is meaningless and can be curtailed brutally with a swift bullet. In contrast, Jesus' gospel of grace offers forgiveness for sin (Matt. 26:28), instead of retributive justice, and hope for a future (Tit. 2:13). The way of redemption is superior to retribution!Copyright ©2010, Martin Baggs

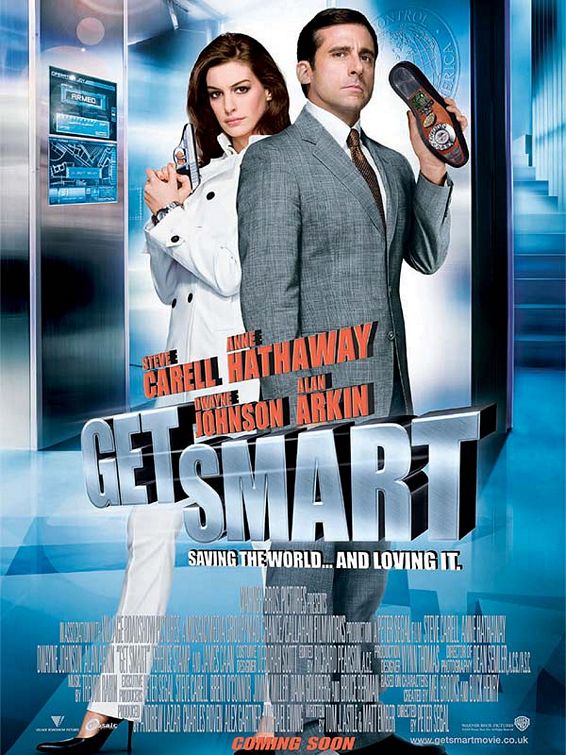

The Chief (Alan Arkin, Little Miss Sunshine), though, won't hear of it. Smart is too smart, and too good at his job to be released into the field. Even when Smart scores high enough on the field operative test to be considered for a numbered agent's job, he is not promoted to that role. He is denied his ambition.

The Chief (Alan Arkin, Little Miss Sunshine), though, won't hear of it. Smart is too smart, and too good at his job to be released into the field. Even when Smart scores high enough on the field operative test to be considered for a numbered agent's job, he is not promoted to that role. He is denied his ambition. One of the pleasures of Get Smart is the comedic acting of Carrell. A fine straight man, here he is straighter than an arrow and the butt of many of the jokes, a sympathetic spy. He has excellent chemistry with Hathaway. And even Dwayne "The Rock" Johnson pitches an acceptable performance as Agent 23, a field operative relegated to analysis.

One of the pleasures of Get Smart is the comedic acting of Carrell. A fine straight man, here he is straighter than an arrow and the butt of many of the jokes, a sympathetic spy. He has excellent chemistry with Hathaway. And even Dwayne "The Rock" Johnson pitches an acceptable performance as Agent 23, a field operative relegated to analysis.

Mika's daily routine, of ritual, or making a special nightcap of handmade hot chocolate (hence the title in both French and English) supposedly underscores her love for her husband and step-son. This warmth is further "apparent" in her acceptance of Jeanne who unexpectedly shows up at their large estate. Yet, underlying this warmth is a coldness that comes out in the subtle looks that Huppert casts at certain points. The love is a mask that hides something darker within. Her happiness is merely a facade.

Mika's daily routine, of ritual, or making a special nightcap of handmade hot chocolate (hence the title in both French and English) supposedly underscores her love for her husband and step-son. This warmth is further "apparent" in her acceptance of Jeanne who unexpectedly shows up at their large estate. Yet, underlying this warmth is a coldness that comes out in the subtle looks that Huppert casts at certain points. The love is a mask that hides something darker within. Her happiness is merely a facade. At one point Mika says to Andre, "Instead of loving, I say 'I love you', and people believe me. I have real power in my mind. I calculate everything." She is fooling those around her, as her husband points out:. But she retorts, "Some people fool themselves."

At one point Mika says to Andre, "Instead of loving, I say 'I love you', and people believe me. I have real power in my mind. I calculate everything." She is fooling those around her, as her husband points out:. But she retorts, "Some people fool themselves." When Jeanne is accepted into the family mansion, Andre discovers that she is a talented and aspiring pianist herself, unlike his aimless son, who is threatened by her presence. A significant clue to this mystery is in the chocolate-brown throw-wrap that Mika is crocheting. Hanging over the back of the couch, it looks like a spider's web waiting to snare her latest victim. And the emotionally enigmatic Mika could be the spider at the center of this web. Are the accidents really accidents? Or are they coldly calculated means to an end? Indeed, does Mika have a deep-seated psychosis crying out for help?

When Jeanne is accepted into the family mansion, Andre discovers that she is a talented and aspiring pianist herself, unlike his aimless son, who is threatened by her presence. A significant clue to this mystery is in the chocolate-brown throw-wrap that Mika is crocheting. Hanging over the back of the couch, it looks like a spider's web waiting to snare her latest victim. And the emotionally enigmatic Mika could be the spider at the center of this web. Are the accidents really accidents? Or are they coldly calculated means to an end? Indeed, does Mika have a deep-seated psychosis crying out for help?

DNA evidence at the 11th hour that tied the defendant to the crime. CJ believes Hunter fabricated the evidence and had it planted to secure his convictions.

DNA evidence at the 11th hour that tied the defendant to the crime. CJ believes Hunter fabricated the evidence and had it planted to secure his convictions. When CJ discusses his suspicions with his editor, he cannot offer any proof and is ordered off the "case". Of course where would the movie be if he did just that. Instead he pursues a relationship with Ella Crystal (Amber Tamblyn), an assistant DA who works for Hunter. And he concocts a scheme where he will frame himself for a random murder, and document the DA producing the DNA evidence at the very last minute. In this way he thinks he can complete his investigation, bring it to the spotlight with maximum flair, and win a Pulitzer prize.

When CJ discusses his suspicions with his editor, he cannot offer any proof and is ordered off the "case". Of course where would the movie be if he did just that. Instead he pursues a relationship with Ella Crystal (Amber Tamblyn), an assistant DA who works for Hunter. And he concocts a scheme where he will frame himself for a random murder, and document the DA producing the DNA evidence at the very last minute. In this way he thinks he can complete his investigation, bring it to the spotlight with maximum flair, and win a Pulitzer prize. So why would CJ frame himself for murder? To capture the prize and secure a promotion. He is willing to put everything on the line, including his freedom and his very life, for this goal. In the courtroom his future lies in the hands of the jury of his 12 peers. Later, his future lies in the hands of Ella, as she must choose between her love for CJ and her loyalty to Hunter.

So why would CJ frame himself for murder? To capture the prize and secure a promotion. He is willing to put everything on the line, including his freedom and his very life, for this goal. In the courtroom his future lies in the hands of the jury of his 12 peers. Later, his future lies in the hands of Ella, as she must choose between her love for CJ and her loyalty to Hunter.

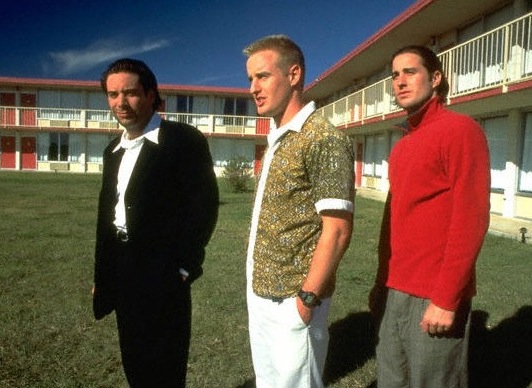

Dignan and Anthony are joined by their friend Bob (Robert Musgrave) as a trio of would-be criminals bent on a life of crime. Dignan is the "mastermind" and has plotted a crime spree that will put them on the map; or at least make them visible to local crime boss Mr. Henry (James Caan). If Dignan is the brains and Anthony is the brawn, Bob's main qualification is that he has a car and hence can be the getaway driver. These three low-life losers are striving to be gangsters; some might describe them as misfit mobsters.

Dignan and Anthony are joined by their friend Bob (Robert Musgrave) as a trio of would-be criminals bent on a life of crime. Dignan is the "mastermind" and has plotted a crime spree that will put them on the map; or at least make them visible to local crime boss Mr. Henry (James Caan). If Dignan is the brains and Anthony is the brawn, Bob's main qualification is that he has a car and hence can be the getaway driver. These three low-life losers are striving to be gangsters; some might describe them as misfit mobsters. The second metaphoric use of the bottle rocket is the misfit's unwillingness to embrace adulthood. Fireworks are for kids. The heroes' desire to buy these rockets and let them off from their vehicle demonstrates their lack of responsibility and avoidance of growing up. They are still just boys in men's clothes. Their dangerous adventures belie their naiveté.

The second metaphoric use of the bottle rocket is the misfit's unwillingness to embrace adulthood. Fireworks are for kids. The heroes' desire to buy these rockets and let them off from their vehicle demonstrates their lack of responsibility and avoidance of growing up. They are still just boys in men's clothes. Their dangerous adventures belie their naiveté. Anderson's films (e.g.,

Anderson's films (e.g.,

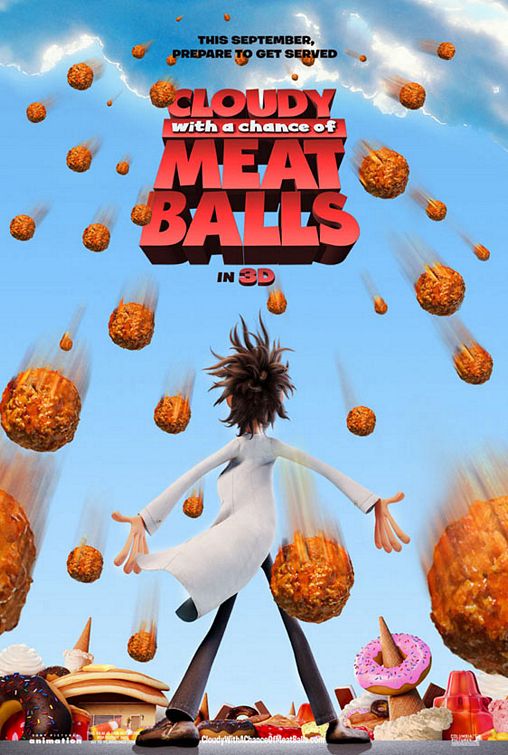

overcome this problem, the town mayor (voice of Bruce Campbell) comes up with a scheme to turn the liability into an asset by creating an entertainment theme park out of sardines, much like Disneyland but with the canned fish. But during the grand opening celebrations, misfit Flint manages to mar the events further ostracizing himself in the eyes of his fellow townsfolk. To make matters worse, a national TV news channel has sent an intern weather reporter Sam Sparks (voice of Anna Faris) to cover the ceremony.

overcome this problem, the town mayor (voice of Bruce Campbell) comes up with a scheme to turn the liability into an asset by creating an entertainment theme park out of sardines, much like Disneyland but with the canned fish. But during the grand opening celebrations, misfit Flint manages to mar the events further ostracizing himself in the eyes of his fellow townsfolk. To make matters worse, a national TV news channel has sent an intern weather reporter Sam Sparks (voice of Anna Faris) to cover the ceremony. Flint and Sam come into contact when his latest invention, a machine that transforms water into food, goes out of control and blasts into the atmosphere . . . where there are clouds full of water. The first "rainfall" is cheeseburgers, and is seen as a miracle, like manna from heaven. And when Flint realizes he can control what is delivered from the sky, he begins to take orders. The mayor even sees a new way to exploit this apparent blessing. But predictably, matters get complicated until chaos ensues threatening the entire globe. The world needs a savior, and Flint is that man!

Flint and Sam come into contact when his latest invention, a machine that transforms water into food, goes out of control and blasts into the atmosphere . . . where there are clouds full of water. The first "rainfall" is cheeseburgers, and is seen as a miracle, like manna from heaven. And when Flint realizes he can control what is delivered from the sky, he begins to take orders. The mayor even sees a new way to exploit this apparent blessing. But predictably, matters get complicated until chaos ensues threatening the entire globe. The world needs a savior, and Flint is that man! Against this big picture scenario, the real heart and theme of the film is much smaller and down-home: communicating "I love you". Flint's mom was a good communicator, but his unibrowed dad has a different communication style: "Son, not every sardine was meant to swim," he tells Flint early on. But Flint replies, "I don't understand fishing metaphors, dad!" They are not on the same wavelength. His dad is an uninspiring and practical man, who goes about his work with an air of defeatism. He does not understand Flint's world or his dreams. There is more than a generational gap, here; there is a vocational chasm. Flint cannot understand his dad's aphorisms; Tim cannot understand his son's inventions.

Against this big picture scenario, the real heart and theme of the film is much smaller and down-home: communicating "I love you". Flint's mom was a good communicator, but his unibrowed dad has a different communication style: "Son, not every sardine was meant to swim," he tells Flint early on. But Flint replies, "I don't understand fishing metaphors, dad!" They are not on the same wavelength. His dad is an uninspiring and practical man, who goes about his work with an air of defeatism. He does not understand Flint's world or his dreams. There is more than a generational gap, here; there is a vocational chasm. Flint cannot understand his dad's aphorisms; Tim cannot understand his son's inventions.

Moon is virtually a one-man show built around Sam Rockwell as Sam Bell (although the voice of Kevin Spacey is heard as his computer companion). Rockwell carries the movie on his shoulders, showing us he has the acting chops to do so and be in front of the camera for almost the entire film.

Moon is virtually a one-man show built around Sam Rockwell as Sam Bell (although the voice of Kevin Spacey is heard as his computer companion). Rockwell carries the movie on his shoulders, showing us he has the acting chops to do so and be in front of the camera for almost the entire film. With two weeks left to go, he is counting the days until he can return to earth to be reunited with his wife and young daughter, who was just born when he left on this mission. Unlike in "Space Oddity", where Bowie sings, "Ground control to major Tom," there is no contact between ground control (or Lunar Industries) and Bell, as the satellite link has been damaged. So, Bell is completely alone, apart from GERTY, an artificial intelligent computer, and infrequent video recordings sent to him from earth.

With two weeks left to go, he is counting the days until he can return to earth to be reunited with his wife and young daughter, who was just born when he left on this mission. Unlike in "Space Oddity", where Bowie sings, "Ground control to major Tom," there is no contact between ground control (or Lunar Industries) and Bell, as the satellite link has been damaged. So, Bell is completely alone, apart from GERTY, an artificial intelligent computer, and infrequent video recordings sent to him from earth. Moon opens us up to the question of what effects long-term isolation has on a person, particularly his psyche, but it does not really answer its own question. It is clear that depriving a person from human interaction for an extended period will cause some damage, but how much is the big question. With the future possibility of manned space flights to mars or beyond, and today's orbital space-station a reality, these are legitimate questions. Man is a relational being, and needs social engagement to thrive and grow emotionally. We even find our true identity through relationship, but specifically our relationship with God, our creator (Jn. 1:12).

Moon opens us up to the question of what effects long-term isolation has on a person, particularly his psyche, but it does not really answer its own question. It is clear that depriving a person from human interaction for an extended period will cause some damage, but how much is the big question. With the future possibility of manned space flights to mars or beyond, and today's orbital space-station a reality, these are legitimate questions. Man is a relational being, and needs social engagement to thrive and grow emotionally. We even find our true identity through relationship, but specifically our relationship with God, our creator (Jn. 1:12).

For their final con, Stephen focuses on Penelope Stamp (Rachel Weisz), a lonely and eccentric New Jersey heiress. Living in a huge mansion, her pastime is borrowing other people's hobbies. When she finds a hobby she finds interesting, she teaches it to herself from books. That is her life. So Stephen writes Bloom as a smuggler who falls in love with Penelope, and brings her into their latest smuggling scheme.

For their final con, Stephen focuses on Penelope Stamp (Rachel Weisz), a lonely and eccentric New Jersey heiress. Living in a huge mansion, her pastime is borrowing other people's hobbies. When she finds a hobby she finds interesting, she teaches it to herself from books. That is her life. So Stephen writes Bloom as a smuggler who falls in love with Penelope, and brings her into their latest smuggling scheme. Do we seek independence and self-control? Sometimes we feel the burden of living under the authority of another. Our natural tendency is to want to throw off authority and define our own life. But what is the place for God? Where does he fit? Proverbs 21:1 says, "The king's heart is in the hand of the LORD; he directs it like a watercourse wherever he pleases." God oversees the course of life to bring matters to his sovereign plan. Life, like it or not, employs a script written for us by the Writer.

Do we seek independence and self-control? Sometimes we feel the burden of living under the authority of another. Our natural tendency is to want to throw off authority and define our own life. But what is the place for God? Where does he fit? Proverbs 21:1 says, "The king's heart is in the hand of the LORD; he directs it like a watercourse wherever he pleases." God oversees the course of life to bring matters to his sovereign plan. Life, like it or not, employs a script written for us by the Writer. Toward the end of the film, as the con develops, the lines between reality and deception blur, for both the view and for Bloom. We don't know what is happening, as he does not. But Stephen leaves us with two thoughts. The first is on cons: "The perfect con is one where everyone involved gets just what they wanted." Stephen wanted to write the perfect con, the perfect written life. Bloom wanted to find himself, his real person. Penelope wanted to find something or someone beyond mere hobbies. If they all get what they want, including the mark (Penelope in this case), is the con morally acceptable? If the mark willingly gives us the money and thinks he or she has gained something, is this still ethically wrong? This comes down to ends and means. The con is a deception, a ruse. It is breach of confidence; after all that is what the con-game is all about. Lying. Deceiving. Stealing. How can this be OK, even if all get what they want? It can't.

Toward the end of the film, as the con develops, the lines between reality and deception blur, for both the view and for Bloom. We don't know what is happening, as he does not. But Stephen leaves us with two thoughts. The first is on cons: "The perfect con is one where everyone involved gets just what they wanted." Stephen wanted to write the perfect con, the perfect written life. Bloom wanted to find himself, his real person. Penelope wanted to find something or someone beyond mere hobbies. If they all get what they want, including the mark (Penelope in this case), is the con morally acceptable? If the mark willingly gives us the money and thinks he or she has gained something, is this still ethically wrong? This comes down to ends and means. The con is a deception, a ruse. It is breach of confidence; after all that is what the con-game is all about. Lying. Deceiving. Stealing. How can this be OK, even if all get what they want? It can't.

![[3hrt.jpg]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgzfbrgarAs28-JaekaeeaBJZkTCN_uEKzdAJCbSEe8PBulm5Syx8Qtbrl0jCTYL1hgNbYEsUhuG1Tj7HC40qYBxSyl0TwTOpssDtcHtBUCkgP212L0kp9Kk3OjK-I6i7HkG0g-41HjPOU/s1600/3hrt.jpg)

Life will always have adversity, peaks and valleys. That is expected. If we avoid the valleys through self-isolation, we miss out on the high notes too. Life is meant to be lived in relationship. When God made Adam, he saw that he was alone and that it was not good (Gen. 2:18). The only time this phrase (not good) occurs in the opening chapters of the book of Genesis is related to Adam's isolation. So God made Adam a companion, Eve (Gen. 2:22-24). Apart from friendships, life becomes colorless and dour, even depressing. As Macon says, "Now I'm far from everyone. I don't have any friends anymore."

Life will always have adversity, peaks and valleys. That is expected. If we avoid the valleys through self-isolation, we miss out on the high notes too. Life is meant to be lived in relationship. When God made Adam, he saw that he was alone and that it was not good (Gen. 2:18). The only time this phrase (not good) occurs in the opening chapters of the book of Genesis is related to Adam's isolation. So God made Adam a companion, Eve (Gen. 2:22-24). Apart from friendships, life becomes colorless and dour, even depressing. As Macon says, "Now I'm far from everyone. I don't have any friends anymore." on what is happening to him as his relationship with Muriel develops: "I'm beginning to think that maybe it's not just how much you love someone. Maybe what matters is who you are when you're with them." He loved Sarah. But ultimately this did not help his marriage. He was not available to her emotionally in the latter part of their relationship. He needed to be there with her. Muriel showed him who he could be. Though it led to an adulterous relationship, he needed Muriel to be able to develop as a person.

on what is happening to him as his relationship with Muriel develops: "I'm beginning to think that maybe it's not just how much you love someone. Maybe what matters is who you are when you're with them." He loved Sarah. But ultimately this did not help his marriage. He was not available to her emotionally in the latter part of their relationship. He needed to be there with her. Muriel showed him who he could be. Though it led to an adulterous relationship, he needed Muriel to be able to develop as a person. Geena Davis plays a terrific Muriel, and worthily won the Oscar for Best Supporting Actress. She has a shotgun approach, spewing words and thoughts a mile a minute. Hers is a zany spontaneity that is balanced by practical ideas that work.

Geena Davis plays a terrific Muriel, and worthily won the Oscar for Best Supporting Actress. She has a shotgun approach, spewing words and thoughts a mile a minute. Hers is a zany spontaneity that is balanced by practical ideas that work.

Almost 15 years later Leconte directed a very similar film,

Almost 15 years later Leconte directed a very similar film,  M. Hire is not so much lonely as reclusive and maladjusted. He seems resigned to his situation. His voyeuristic spying on his neighbor, creepy as it is, seems harmless. He has no malicious intent. He just wants to watch her. (She should have invested in heavy drapes, but that would have pulled the curtain down on the movie.) Yet, he is certainly not living life to its fullest. He is on the sidelines looking in. He is a spectator rather than a player. Life is meant to be lived. God gave us life, and we can only experience it fully and freshly if we come to Jesus: "I have come that they may have life, and have it more abundantly!" (Jn. 10:10)

M. Hire is not so much lonely as reclusive and maladjusted. He seems resigned to his situation. His voyeuristic spying on his neighbor, creepy as it is, seems harmless. He has no malicious intent. He just wants to watch her. (She should have invested in heavy drapes, but that would have pulled the curtain down on the movie.) Yet, he is certainly not living life to its fullest. He is on the sidelines looking in. He is a spectator rather than a player. Life is meant to be lived. God gave us life, and we can only experience it fully and freshly if we come to Jesus: "I have come that they may have life, and have it more abundantly!" (Jn. 10:10) As M. Hire comes under more and more suspicion, Alice sees him and comes to meet him. In the second half of the film, their interaction develops in surprising ways. In some sense, she is as strange and lonely as he, though in different ways. And Leconte slowly brings the narrative along to an unexpected conclusion.

As M. Hire comes under more and more suspicion, Alice sees him and comes to meet him. In the second half of the film, their interaction develops in surprising ways. In some sense, she is as strange and lonely as he, though in different ways. And Leconte slowly brings the narrative along to an unexpected conclusion.