What would you do if you were crying out to be heard but no one could hear you? And to compound this, suppose you were unable to move. This is the situation that Jean-Dominique Bauby found himself in. His true-life story is told in The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, a slow but moving French movie.

Diving Bell opens with Bauby (Mathieu Amalric) in a hospital bed. The camera stays tight, unmoving. It gives us the view from the patient's perspective. It goes in and out of focus with Bauby. When he blinks, the camera closes. He does not know where he is, or why the people are coming in and out of his field of vision. When he "talks" they cannot hear, since the words are in his head. Slowly he comes to realize he is in a hospital. And worse, he has "locked-in syndrome." All he can move is his left eye. Nothing else.

The first act of the movie is almost surreal, a claustrophobic combination of frustration and confusion. It succeeds in getting the viewer into the position of the patient. If we feel this frustrated, how much more must it be for Jean-Do Bauby.

As the movie unfolds, we see through flashback who Bauby was. Editor of famed fashion magazine, "Elle," he was the prototypical Frenchman -- lover of wine and women. Father of three, he had left his woman, Celine (Emmanuelle Seigner) -- "not my wife, she is the mother of my three children" -- for another. He had been through several affairs. He was seeking the fullness of life; he was seeking relational fulfillment. He found it with his father, who was trapped in an apartment by old-age infirmities, but not with women.

In contrast to this carefree lover of life, Bauby has become trapped in a world all his own, with little to no hope of rescue or emergence. At first he cannot communicate with his caregivers. But rehab nurse Henriette Durand (Marie-Josee Croze) devises a way for him to "talk" -- she reads the letters of the alphabet to him and he blinks at the letter he wants. In this painstaking way, letter by letter, he constructs the words and sentences he wants to communicate. But it is better than no communication.

In contrast to this carefree lover of life, Bauby has become trapped in a world all his own, with little to no hope of rescue or emergence. At first he cannot communicate with his caregivers. But rehab nurse Henriette Durand (Marie-Josee Croze) devises a way for him to "talk" -- she reads the letters of the alphabet to him and he blinks at the letter he wants. In this painstaking way, letter by letter, he constructs the words and sentences he wants to communicate. But it is better than no communication.At first he feels so sorry for himself that he wants to die. "I want death," he says to Henrietta, communicating the enormity of the frustration and lack of control he has. But as he ponders life, he changes his perspective: "I decided to stop pitying myself. Other than my eye, two things aren't paralyzed, my imagination and my memory." And these two are his constant companions.

The movie portrays his memories in flashback sequences, and these let us into what he has lost. The imagination is communicated in a collage of pictures and creative videos. In his imagination he can go anywhere he wants at any time. And he uses this to keep his outlook positive. As the diving bell is a metaphor for the locked-in situation he has no physical escape from, so the butterfly is a metaphor for the freedom he finds in his imagination, his mental escape which keeps him alive.

Before his stroke, he had signed a contract to write a modern-day version of "The Count of Monte Cristo", from a feminine point of view. Now he wants to fulfill his contract, but as a memoir of his life instead. With the help of Claude (Anne Consigny) who becomes his constant "dictation companion," he begins to write this book, one letter at a time.

Along with the way, his frustration is seen in the little things of life. Watching a soccer game, a nurse comes in and turns the TV off. We can feel the pain he experiences as he wants to see the end of the game and yet cannot do a thing about it. In another scene, two telephone installers come to his room and treat him like an idiot, a mute animal who has no feelings. As they leave the room, they rudely mock him, leaving him pierced by their cruelty.

Along with the way, his frustration is seen in the little things of life. Watching a soccer game, a nurse comes in and turns the TV off. We can feel the pain he experiences as he wants to see the end of the game and yet cannot do a thing about it. In another scene, two telephone installers come to his room and treat him like an idiot, a mute animal who has no feelings. As they leave the room, they rudely mock him, leaving him pierced by their cruelty. In several ways, Diving Bell is like The Sea Inside on steroids. Both are slow foreign films. Both are based on true stories. Both deal with men in their prime crushed by an accident. While The Sea Inside's Ramon Sampedros is paralyzed, he can still move his head and speak. He can communicate, Jean-Do Bauby can do neither. While Ramon pursued death with dignity, Jean-Do moved to an acceptance of life. Both are based on stellar acting in conditions requiring total commitment.

In several ways, Diving Bell is like The Sea Inside on steroids. Both are slow foreign films. Both are based on true stories. Both deal with men in their prime crushed by an accident. While The Sea Inside's Ramon Sampedros is paralyzed, he can still move his head and speak. He can communicate, Jean-Do Bauby can do neither. While Ramon pursued death with dignity, Jean-Do moved to an acceptance of life. Both are based on stellar acting in conditions requiring total commitment.In life Bauby looked everywhere for meaning and purpose, not really appreciating what he had. Going from woman to woman looking for love, he gets approval from his father (and don't we all seek parental approval) but cannot settle down with a wife. Yet, only when locked inside himself does he really get to appreciate what he had. Bauby learns to appreciate life, even if it is only lived out in his imagination.

How often do we fail to appreciate what we have? How often do we look at what we are missing, at what others have, and build greedy resentment in our hearts? Diving Bell reminds us that we should be thankful for what we have. Whether it is our children, our spouse, our friends, we must not take them from granted. Let's not wait for a tragic accident to make us realize what we have. As I celebrate the birthday of my beautiful Becca today, I can see my children and my family as gifts from a wonderful God. We can and should count our blessings.

Copyright 2008, Martin Baggs

Set in the late 1950s, Indy is still teaching and pursuing adventures as an archaeologist. This time, though, his enemy is not the Nazis, but the Russian commies, and they don't carry quite the same punch. The leader of this bad band is Col. Dr. Irina Spalko. Cate Blanchett plays her with relish as a wicked cartoonish figure, like Cruella DaVille with a Russian accent. The goal in this chapter is the crystal skull, legendary pointer to El Dorado, city of gold, hidden somewhere in South America.

Set in the late 1950s, Indy is still teaching and pursuing adventures as an archaeologist. This time, though, his enemy is not the Nazis, but the Russian commies, and they don't carry quite the same punch. The leader of this bad band is Col. Dr. Irina Spalko. Cate Blanchett plays her with relish as a wicked cartoonish figure, like Cruella DaVille with a Russian accent. The goal in this chapter is the crystal skull, legendary pointer to El Dorado, city of gold, hidden somewhere in South America. Crystal Skull is shot in the same comic book style, with the same types of action sequences as the previous three episodes. So much so, in fact, that this could have come out in the 1990s. It is filled with obvious references to the earlier movies: truck chases, fist fights, poison-tipped dart-blowing natives, booby-trapped tombs. The most exciting chase occurs early in the movie, when Williams meets Jones, and they flee the Russians on Mutt's motorcycle. This had all the thrills of the earlier movies.

Crystal Skull is shot in the same comic book style, with the same types of action sequences as the previous three episodes. So much so, in fact, that this could have come out in the 1990s. It is filled with obvious references to the earlier movies: truck chases, fist fights, poison-tipped dart-blowing natives, booby-trapped tombs. The most exciting chase occurs early in the movie, when Williams meets Jones, and they flee the Russians on Mutt's motorcycle. This had all the thrills of the earlier movies. The first act is strong, showing us an older and more worldly-wise Jones, and introducing us to a young Mutt Williams. The second act is more predictable. The third act, where Karen Allen reappears as Marion Ravenwood pits the two ex-lovers, Marion and Indiana, once again verbally at each other's throats. And they pick up where they left off in Raiders. Indeed, a big part of the fun of Crystal Skull is seeing these two love-birds fighting and squabbling again.

The first act is strong, showing us an older and more worldly-wise Jones, and introducing us to a young Mutt Williams. The second act is more predictable. The third act, where Karen Allen reappears as Marion Ravenwood pits the two ex-lovers, Marion and Indiana, once again verbally at each other's throats. And they pick up where they left off in Raiders. Indeed, a big part of the fun of Crystal Skull is seeing these two love-birds fighting and squabbling again.

f sand for the head, but despite this trick still triggers the final trap: a large boulder the size of a truck rolling down to crush him. When he finally gets out, with the help of his trusty bullwhip, he finds his arch-enemy, the French Belloq (Paul Freeman), waiting with a hostile tribe of headhunters, and has to relinquish the relic. The classic shot, foreshortened via long telephoto lens, of Indy running in front of these native Indians before diving into the river is one seared into the American movie-goers memory.

f sand for the head, but despite this trick still triggers the final trap: a large boulder the size of a truck rolling down to crush him. When he finally gets out, with the help of his trusty bullwhip, he finds his arch-enemy, the French Belloq (Paul Freeman), waiting with a hostile tribe of headhunters, and has to relinquish the relic. The classic shot, foreshortened via long telephoto lens, of Indy running in front of these native Indians before diving into the river is one seared into the American movie-goers memory.  From America to Nepal, where he teams up with old flame Marion Ravenwood (Karen Allen), to Cairo Indy paves a trail that is anything but silent. As Raiders progresses, the action comes thick and fast. The world of the late 1930s is changing, and the Germans want the ark because of the power of God that it is supposed to provide to its bearer. But Indiana Jones symbolizes all that is good about America in contrast to the highly organized and efficient but evil Germans. With such memorable scenes as the marketplace fight and standoff with the giant scimitar-bearing thug, and the truck chase culminating in Indy being dragged on his belly, Raiders of the Lost Ark is a modern-day classic, yet another winner from the Spielberg-Lucas stable.

From America to Nepal, where he teams up with old flame Marion Ravenwood (Karen Allen), to Cairo Indy paves a trail that is anything but silent. As Raiders progresses, the action comes thick and fast. The world of the late 1930s is changing, and the Germans want the ark because of the power of God that it is supposed to provide to its bearer. But Indiana Jones symbolizes all that is good about America in contrast to the highly organized and efficient but evil Germans. With such memorable scenes as the marketplace fight and standoff with the giant scimitar-bearing thug, and the truck chase culminating in Indy being dragged on his belly, Raiders of the Lost Ark is a modern-day classic, yet another winner from the Spielberg-Lucas stable.

This was a contrast to the extended scenes and interactions around Battlecry, a Christian movement in San Francisco aimed at teens. When the organizers appeared on the steps of City Hall, the same steps where gay married couples appeared earlier, they were met with an anti-Christian gay rally. This, in turn, caused Christians to decry the gays for their lifestyle. It was a classic polarizing and dividing event. Merchant, meanwhile took time to talk to some of the ralliers on both sides. One in particular, Sister Mary Timothy of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, a drag-queen nun, shared her/his views to Merchant as he was actually heard. Respectful listening created space for views to be shared.

This was a contrast to the extended scenes and interactions around Battlecry, a Christian movement in San Francisco aimed at teens. When the organizers appeared on the steps of City Hall, the same steps where gay married couples appeared earlier, they were met with an anti-Christian gay rally. This, in turn, caused Christians to decry the gays for their lifestyle. It was a classic polarizing and dividing event. Merchant, meanwhile took time to talk to some of the ralliers on both sides. One in particular, Sister Mary Timothy of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, a drag-queen nun, shared her/his views to Merchant as he was actually heard. Respectful listening created space for views to be shared.

Wilson gives Francis the innate characteristics that define first-borns: order and control. Those of you who know or live with first-borns (and I am a first-born) understand first-hand the tensions that these bring. At one point, when an Indian waiter asks the three for their dinner orders, Francis orders for them all, not giving Jack or Peter (Adrian Brody) a chance to decide for themselves. This is a source of tension for them.

Wilson gives Francis the innate characteristics that define first-borns: order and control. Those of you who know or live with first-borns (and I am a first-born) understand first-hand the tensions that these bring. At one point, when an Indian waiter asks the three for their dinner orders, Francis orders for them all, not giving Jack or Peter (Adrian Brody) a chance to decide for themselves. This is a source of tension for them.  As they journey through India, the home of a million deities, experiencing different religions, praying to different gods, it is interesting that they end up in a Christian church praying to the one, true God. This may be unintentional, but is a metaphor for real life. Many of us seek spiritual awakening and enlightenment, looking into many religions. But the truth that can set us free can only be found in the person of Jesus Christ.

As they journey through India, the home of a million deities, experiencing different religions, praying to different gods, it is interesting that they end up in a Christian church praying to the one, true God. This may be unintentional, but is a metaphor for real life. Many of us seek spiritual awakening and enlightenment, looking into many religions. But the truth that can set us free can only be found in the person of Jesus Christ. Symbolically, in running to catch the train to the airport at the end, a matching book-end to Bill Murray's cameo scene at the beginning, they let go of the baggage they have been carrying all movie-long. They have arrived at a level of self-understanding and sibling-reconciliation. Their emotional baggage has been released. What about us? Are we holding on to the baggage of our childhood? Are we carrying around a weight of unnecessary issues that is hindering our relational growth? Are we remaining unreconciled to family members? The Darjeeeling Limited challenges us to come to our personal catharsis, to take the journey to rebond with brothers or sisters, and become true friends.

Symbolically, in running to catch the train to the airport at the end, a matching book-end to Bill Murray's cameo scene at the beginning, they let go of the baggage they have been carrying all movie-long. They have arrived at a level of self-understanding and sibling-reconciliation. Their emotional baggage has been released. What about us? Are we holding on to the baggage of our childhood? Are we carrying around a weight of unnecessary issues that is hindering our relational growth? Are we remaining unreconciled to family members? The Darjeeeling Limited challenges us to come to our personal catharsis, to take the journey to rebond with brothers or sisters, and become true friends.

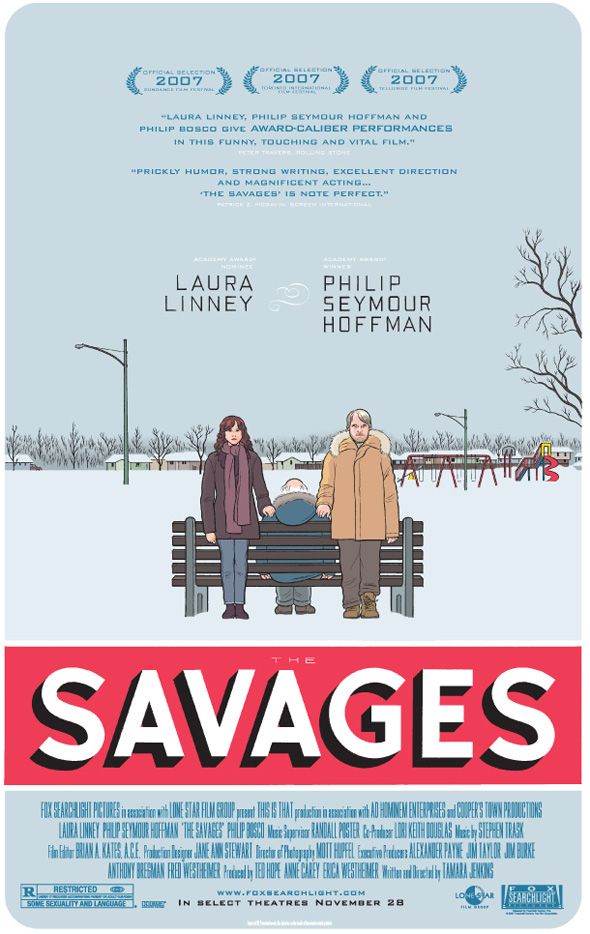

Wendy and Jon come to find Lenny in restraints in the hospital -- for his own safety. It is clear he cannot live in his dead girlfriend's house: her kids want to sell it. It is also clear he cannot live on his own. It falls on his kids, no longer part of his life, to become involved. It is their obligation, their responsibility.

Wendy and Jon come to find Lenny in restraints in the hospital -- for his own safety. It is clear he cannot live in his dead girlfriend's house: her kids want to sell it. It is also clear he cannot live on his own. It falls on his kids, no longer part of his life, to become involved. It is their obligation, their responsibility.  Jon, being the older and employed child, takes the responsibility of finding a nursing home. But it is not picture perfect. Wendy is the guilt-ridden child, who cannot bear that her dad will be in a place that smells, that reeks of decaying life and imminent death. She wants him to be in a "retirement home" where there is classical music and sweet smelling flowers -- at least that's what the DVD promo materials from these make them look like. And burdened by guilt, Wendy moves in with slobbish Jon, a sort of siblings Odd Couple.

Jon, being the older and employed child, takes the responsibility of finding a nursing home. But it is not picture perfect. Wendy is the guilt-ridden child, who cannot bear that her dad will be in a place that smells, that reeks of decaying life and imminent death. She wants him to be in a "retirement home" where there is classical music and sweet smelling flowers -- at least that's what the DVD promo materials from these make them look like. And burdened by guilt, Wendy moves in with slobbish Jon, a sort of siblings Odd Couple.

from Zia and his generals for the lack of support by the CIA. Taking it in stride, he is ready to leave with political platitudes preached, when Zia makes him promise to visit a refugee camp that very day. Flying there in a waiting helicoptor, Wilson tells lapdog aid Bonnie Bach (Amy Adams), "You know you've reached rock bottom when you're told you have character flaws by a man who hanged his predecessor in a military coup."

from Zia and his generals for the lack of support by the CIA. Taking it in stride, he is ready to leave with political platitudes preached, when Zia makes him promise to visit a refugee camp that very day. Flying there in a waiting helicoptor, Wilson tells lapdog aid Bonnie Bach (Amy Adams), "You know you've reached rock bottom when you're told you have character flaws by a man who hanged his predecessor in a military coup." But this trip proves life-changing for Wilson. He sees widows fighting for a few grains of rice, children without arms and legs due to booby-trapped candies and toys, and tents housing families as far as the eye could see. Seeing first-hand the results of bombs, mines and war, he returns prepared to make a difference.

But this trip proves life-changing for Wilson. He sees widows fighting for a few grains of rice, children without arms and legs due to booby-trapped candies and toys, and tents housing families as far as the eye could see. Seeing first-hand the results of bombs, mines and war, he returns prepared to make a difference. With the help of CIA agent Gust Avrakotos (Philip Seymour Hoffman), an undiplomatic forthright agent who gets things done, Wilson, Avrakotos and Herring prove an unlikely trio who changed things forever while the world slept. Slowly, Wilson raises the budget to $40M and then $500M and then over a billion. Sending modern weapons to combat the Russian Hind helicopter gunships, Wilson gets an education and a victory in this covert war, a war that the US never wanted, but a war that they won . . . and lost.

With the help of CIA agent Gust Avrakotos (Philip Seymour Hoffman), an undiplomatic forthright agent who gets things done, Wilson, Avrakotos and Herring prove an unlikely trio who changed things forever while the world slept. Slowly, Wilson raises the budget to $40M and then $500M and then over a billion. Sending modern weapons to combat the Russian Hind helicopter gunships, Wilson gets an education and a victory in this covert war, a war that the US never wanted, but a war that they won . . . and lost.

g firm. And mom is an overprotective mother, who does everything for her sons. When she walks in on Jim taking a bath to give him a towel and a hug, we realize she has not let her sons grow up.

g firm. And mom is an overprotective mother, who does everything for her sons. When she walks in on Jim taking a bath to give him a towel and a hug, we realize she has not let her sons grow up. which Anika replies, "You think I'm fun and cheery?" She makes lemonade out of the lemon that Jim is.

which Anika replies, "You think I'm fun and cheery?" She makes lemonade out of the lemon that Jim is.

conspirator in the assassination of the man that brought this nation together. "

conspirator in the assassination of the man that brought this nation together. " As in other movies in this genre, one must suspend disbelief to enjoy the ride. It is totally implausible that a treasure-hunter, even with a techno-geek foil like Riley, could break into the office of the queen in Buckingham Palace escape the country and then kidnap the President of the United States of America and get away with it. If the secret service was as poor as they appear here, we would be seeing a new president every other week. But that aside, to decipher the code and find the treasure Gates and crew have to go these cinematic locations and solve the clues without getting caught, else there is no story.

As in other movies in this genre, one must suspend disbelief to enjoy the ride. It is totally implausible that a treasure-hunter, even with a techno-geek foil like Riley, could break into the office of the queen in Buckingham Palace escape the country and then kidnap the President of the United States of America and get away with it. If the secret service was as poor as they appear here, we would be seeing a new president every other week. But that aside, to decipher the code and find the treasure Gates and crew have to go these cinematic locations and solve the clues without getting caught, else there is no story. Book of Secrets is a thrill ride, for sure. Not in the same realm as the Indiana Jones trilogy (and I can't wait to see and review the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull in June), yet it is an exciting movie that you can watch with your children. It is a perfect example of the scriptural injunction: "Honor your father and your mother" (Exod. 20:12). One of the ten commandments given to Moses, we are commanded to honor the names of our parents, and presumably those of our ancestors. As Gates sees a clear need to give 100% to the cause of clearing his ancestor's name, so we need to be committed to honoring those of our lineage. And hopefully, we will not be called on to break into the oval office to do so!

Book of Secrets is a thrill ride, for sure. Not in the same realm as the Indiana Jones trilogy (and I can't wait to see and review the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull in June), yet it is an exciting movie that you can watch with your children. It is a perfect example of the scriptural injunction: "Honor your father and your mother" (Exod. 20:12). One of the ten commandments given to Moses, we are commanded to honor the names of our parents, and presumably those of our ancestors. As Gates sees a clear need to give 100% to the cause of clearing his ancestor's name, so we need to be committed to honoring those of our lineage. And hopefully, we will not be called on to break into the oval office to do so!

When the Clutter family is brutally murdered in their Kansas home, Capote is drawn to the story like a moth to a flame. And like that same moth, this flame will change Capote forever. Capote senses a huge story and asks Harper Lee, the author of "To Kill a Mocking Bird," to accompany him to visit the Kansas town as his research assistant. She is the perfect foil to Capote, grounded and calm.

When the Clutter family is brutally murdered in their Kansas home, Capote is drawn to the story like a moth to a flame. And like that same moth, this flame will change Capote forever. Capote senses a huge story and asks Harper Lee, the author of "To Kill a Mocking Bird," to accompany him to visit the Kansas town as his research assistant. She is the perfect foil to Capote, grounded and calm. Along the way, Capote's relationship to Smith turns somewhat personal, he becomes involved. Truman Capote becomes conflicted, wanting his book to end but knowing that it would only do so with an execution or a pardon. Through it all, though, seeing them dance a verbal tango, or watching Capote tap the keys of his manual typewriter is simply not enthralling cinema.

Along the way, Capote's relationship to Smith turns somewhat personal, he becomes involved. Truman Capote becomes conflicted, wanting his book to end but knowing that it would only do so with an execution or a pardon. Through it all, though, seeing them dance a verbal tango, or watching Capote tap the keys of his manual typewriter is simply not enthralling cinema.

When Jean shows up on Einar's doorstep with her daughter, he learns that Griff is his granddaughter, the child of his late son, Griff. A shock indeed! His first interaction with the young Griff is less than polite, but he allows them both to stay, if just for a couple of weeks. But that is long enough for her to get a job at local diner, hook up with town sheriff Crane Curtis (Josh Lucas), and for her abusive boyfriend Gary (Damian Lewis) to find her and show up in town.

When Jean shows up on Einar's doorstep with her daughter, he learns that Griff is his granddaughter, the child of his late son, Griff. A shock indeed! His first interaction with the young Griff is less than polite, but he allows them both to stay, if just for a couple of weeks. But that is long enough for her to get a job at local diner, hook up with town sheriff Crane Curtis (Josh Lucas), and for her abusive boyfriend Gary (Damian Lewis) to find her and show up in town.  But An Unfinished Life is a movie of redemption and forgiveness. During the few weeks that Jean and Griff are living in town, Einar learns what it means to have a relative, a granddaughter, to love. And amidst such great actors, Becca Gardner, in her second movie role, steals the show. She wins Einar's heart and softens him until he is ready to confront Jean.

But An Unfinished Life is a movie of redemption and forgiveness. During the few weeks that Jean and Griff are living in town, Einar learns what it means to have a relative, a granddaughter, to love. And amidst such great actors, Becca Gardner, in her second movie role, steals the show. She wins Einar's heart and softens him until he is ready to confront Jean.  Early on, learning that the bear is back in town, Einar takes his rifle to go kill it, only to be prevented by Sheriff Curtis. The fish and wildlife folks sedate and capture it instead. This is how Einar deals with his problems -- a quick kill to put it behind him, a permanent solution, out of his immediate attention. But the effects of the bear are apparent and face him every day in Mitch's scars. Mitch, on the other hand, wants Einar to visit the bear, now in the town zoo, and even to feed it. Mitch has faced his foe, placed no blame, and held no bitterness. He is willing to move on, despite the consequences, and live his life, difficult though it is, to the finish. Mitch sees beyond to a future that embraces all that life has thrown at him. Even when the bear escapes and somehow returns to Mitch, and runs at him, Mitch will not (cannot) run. Instead, he stands his ground. He will face life, the good and the bad, but refuses to play the blame game or wallow in pity parties.

Early on, learning that the bear is back in town, Einar takes his rifle to go kill it, only to be prevented by Sheriff Curtis. The fish and wildlife folks sedate and capture it instead. This is how Einar deals with his problems -- a quick kill to put it behind him, a permanent solution, out of his immediate attention. But the effects of the bear are apparent and face him every day in Mitch's scars. Mitch, on the other hand, wants Einar to visit the bear, now in the town zoo, and even to feed it. Mitch has faced his foe, placed no blame, and held no bitterness. He is willing to move on, despite the consequences, and live his life, difficult though it is, to the finish. Mitch sees beyond to a future that embraces all that life has thrown at him. Even when the bear escapes and somehow returns to Mitch, and runs at him, Mitch will not (cannot) run. Instead, he stands his ground. He will face life, the good and the bad, but refuses to play the blame game or wallow in pity parties.