Director: Mike Newell, 2005.

With the series' first British director (Newell, Love in the Time of Cholera) at the helm, Goblet of Fire carries us into the fourth year of Harry Potter's education at Hogwarts. With the series fully developed, there is no need for introductions or recaps. Indeed, there is no mention of the Dursleys, so prominent in the early parts of the first two films. This is a movie focused on wizards and the darkening gloom descending on the wizarding world. Even the opening scene is dark, showing a secret meeting between Voldemort and his closest followers. The tone is set.

After this pre-credit sequence, Harry (Daniel Radcliffe), Ron (Rupert Grint) and Hermione (Emma Watson) join the Weasley family at the Quidditch World Cup Final, arriving by portkey, a new plot device that has two key roles here. This is the only portrayal of quidditch in this movie, another sign that Harry's days of fun are starting to wind down. And we don't actually see any quidditch. It does, however, introduce Viktor Krum (Stanislav Ianevski), the world-famous Hungarian seeker.

After the match, and while wizards are reliving the exploits of the players, Death Eaters descend on the scene and set ablaze the host of tents where the visitors are camped. With flaming fields and chaos as people are running scared, the "Dark Mark" is seen in the sky. This is Voldemort's symbol and a sign that his power is returning, a sign the Ministry of Magic wants to ignore, even forget.

After the match, and while wizards are reliving the exploits of the players, Death Eaters descend on the scene and set ablaze the host of tents where the visitors are camped. With flaming fields and chaos as people are running scared, the "Dark Mark" is seen in the sky. This is Voldemort's symbol and a sign that his power is returning, a sign the Ministry of Magic wants to ignore, even forget.With this as an introduction and dire backdrop, the new year at Hogwarts is enhanced by the presence of pupils from two other schools: the beautiful young woman of Beauxbatons and the strong young men, including Krum, of Durmstrang. They are staying the year at Hogwarts since the school is hosting the famous Triwizard Tournament.

"Eternal glory! That's what awaits the student who wins The Triwizard Tournament, but to accomplish this that student must survive three tasks. Three EXTREMELY DANGEROUS tasks," says Professor Dumbledore (Michael Gambon). It is assumed that the reward of eternal glory is a huge motivation for these adolescents and almost-adults. Transient glory often accompanies victory at events, such as sporting competitions. But that glory fades as quickly as the morning mist, so that we can barely remember who won a year later, let alone decades or centuries after the fact. Eternal glory would remain, extending past death. But eternal glory is due to God alone: "To him who sits on the throne and to the Lamb be praise and honor and glory and power for ever and ever!" (Rev. 5:13) Such eternal glory is not ours to strive for nor to receive. We are not worthy and will never merit such honor. We are, instead, to offer such praise to Jesus and the Father who alone are worthy.

"Eternal glory! That's what awaits the student who wins The Triwizard Tournament, but to accomplish this that student must survive three tasks. Three EXTREMELY DANGEROUS tasks," says Professor Dumbledore (Michael Gambon). It is assumed that the reward of eternal glory is a huge motivation for these adolescents and almost-adults. Transient glory often accompanies victory at events, such as sporting competitions. But that glory fades as quickly as the morning mist, so that we can barely remember who won a year later, let alone decades or centuries after the fact. Eternal glory would remain, extending past death. But eternal glory is due to God alone: "To him who sits on the throne and to the Lamb be praise and honor and glory and power for ever and ever!" (Rev. 5:13) Such eternal glory is not ours to strive for nor to receive. We are not worthy and will never merit such honor. We are, instead, to offer such praise to Jesus and the Father who alone are worthy.The Triwizard tournament is open to three wizards, one from each school, who are over the age of 17. But when the goblet of fire kicks out a fourth name, that of underage Harry Potter, something wicked is afoot. Harry claims his innocence, "I didn't put my name in that cup! I don't want eternal glory, just wanna be . . . " normal. Harry has already had his fill of notoriety and the visibility and responsibility that ensue. Against his wishes he must take part in the tournament. However, he is suspected by almost everyone of magically cheating to make this happen.

This brings up one of the early issues in the Goblet of Fire -- loneliness. Virtually the whole school turns away from Harry. Even his closest friends Ron and Hermione disbelieve him and abandon him. He is isolated. And he cannot forget it since most of the students sport "Potter Stinks" badges. Knowing he is innocent, Harry still has to endure almost a third of the year friendless. Only Dumbledore and Sirius Black, his godfather, believe him but they are not in positions to overtly do much. This is a difficult situation for a teenager, who feeds off peers. It can be so for us, if we are abandoned unfairly. It was infinitely so for Jesus, the Lord of all. Isaiah prophetically describes Jesus, the suffering servant: "He was despised and rejected by men." (Isa. 53:3). Loneliness can be traumatic, leaving a hole in the heart.

The Triwizard tournament becomes the stage for the rest of the film. The three challenges, involving dragons, lake-creatures and mazes, focus the narrative. Brendan Gleason plays Mad Eye Moody, the new Defense Against the Dark Arts teacher, who is pivotal in helping Harry. Mysterious and reckless, Moody appears more related to the students than the faculty.

The Triwizard tournament becomes the stage for the rest of the film. The three challenges, involving dragons, lake-creatures and mazes, focus the narrative. Brendan Gleason plays Mad Eye Moody, the new Defense Against the Dark Arts teacher, who is pivotal in helping Harry. Mysterious and reckless, Moody appears more related to the students than the faculty.In one of his lessons, he gives demonstrations of the three unforgivable curses. These are curses that are never to be used, but were employed by Voldemort and his henchmen in his earlier drive for power. Against the students' wishes, and probably violating school regulations and even ministry law (that's the whole point of being unforgivable), he does them.

Unforgivable actions is another ethical issue. Jesus tells us there is an unforgivable sin. "I tell you, every sin and blasphemy will be forgiven men, but the blasphemy against the Spirit will not be forgiven." (Matt. 12:31). The generally accepted interpretation in Christan thought is that this is focusing on apostasy. According to the Evangelical Dictionary of Theology, this "is best viewed as a total and persistent denial of the presence of God in Christ. It reflects a complete recalcitrance of the heart. Rather than a particular act, it is a disposition of the will." Defying and resisting the work of the Holy Spirit in the mission of Jesus over time causes a hardening of heart, and this resultant hardness leads to the unforgiveable sin.

The climax is powerful and thrilling. Bringing closure to the earlier graveyard scene, Harry witnesses the rise of Voldemort (Ralph Fiennes). "He-Who-Shall-Not-be-Named" becomes "He-Who-Has-Now-Been-Seen" with a new body and a snake-like face. With the re-embodiment of evil, everything is likely to change. This is a portent of things to come in future installments. But, even in reality, the introduction of evil and sin into the world in the Garden of Eden caused everything to change (Gen. 3). Innocence was eradicated, paradise lost. The quiet shameless walks with God was replaced with guilty hiding from him. Sin found its place in the human heart and has not been removed since. The human story changed, although there is a future hope of victory (Rev. 19-21).

The climax is powerful and thrilling. Bringing closure to the earlier graveyard scene, Harry witnesses the rise of Voldemort (Ralph Fiennes). "He-Who-Shall-Not-be-Named" becomes "He-Who-Has-Now-Been-Seen" with a new body and a snake-like face. With the re-embodiment of evil, everything is likely to change. This is a portent of things to come in future installments. But, even in reality, the introduction of evil and sin into the world in the Garden of Eden caused everything to change (Gen. 3). Innocence was eradicated, paradise lost. The quiet shameless walks with God was replaced with guilty hiding from him. Sin found its place in the human heart and has not been removed since. The human story changed, although there is a future hope of victory (Rev. 19-21).Afterwards, in the denouement, Dumbledore tells Harry, "Dark and difficult times lie ahead. Soon we must all face the choice between what is right and what is easy." Choice, an overarching theme in this film series, shows up once again. As the Sorting Hat chose Harry for Gryfindor in The Sorcerer's Stone, so the Goblet of Fire chose Harry as a Triwizard champion here. And as Harry had to make choices, of friends and of actions, in the first two movies, so the scene is set for future choices: right or easy. Life is full of such choices, even for us. To take the easy road or the path less traveled which harbors snares and dangers. It may not be easy but it is the right path, the moral choice. As Jesus said, "narrow the road that leads to life, and only a few find it." (Matt. 7:14)

Copyright ©2009, Martin Baggs

Sent to a concentration camp rather than a prison, his artistic skills draw attention to him and soon Sally is given better treatment than the other prisoners. Of course, better treatment means no forced labor and a little food. But even the Germans in their vanity want someone to paint portraits of themselves. Ultimately, his skills cause him to be moved to Sachsenhausen, another concentration camp.

Sent to a concentration camp rather than a prison, his artistic skills draw attention to him and soon Sally is given better treatment than the other prisoners. Of course, better treatment means no forced labor and a little food. But even the Germans in their vanity want someone to paint portraits of themselves. Ultimately, his skills cause him to be moved to Sachsenhausen, another concentration camp. The Counterfeiters is the true story of this economic warfare strategy of the Germans during WW2. It is the first Austrian movie to win an Oscar for foreign film. Despite the unique narrative premise and attention to period detail, the movie ebbs somewhat. Perhaps there have been too many Holocaust movies and they have cauterized our sensitivities. The main characters are too distant to evoke emotional identification. We watch the film but don't get caught up in a real care for them. Herzog is too nice as a Nazi leader, perhaps trying to motivate these men to quality work. Sally is caught between his criminal character and the moral dilemma he faces.

The Counterfeiters is the true story of this economic warfare strategy of the Germans during WW2. It is the first Austrian movie to win an Oscar for foreign film. Despite the unique narrative premise and attention to period detail, the movie ebbs somewhat. Perhaps there have been too many Holocaust movies and they have cauterized our sensitivities. The main characters are too distant to evoke emotional identification. We watch the film but don't get caught up in a real care for them. Herzog is too nice as a Nazi leader, perhaps trying to motivate these men to quality work. Sally is caught between his criminal character and the moral dilemma he faces. A contrast comes in the person of Adolf Berger (August Diehl), an idealistic prisoner working in the dark room, who has lost his family in other concentration camps. He wants to fight back in any way possible. And the best way he can is to sabotage the negatives of the fake pounds. By stalling these counterfeiting efforts he is fighting the enemy. So while Sally is actively working with the Germans to keep his life, Berger is only ostensibly working with them while actually working against them. When Herzog realizes things are not on track he makes it clear: produce results or targeted men will die. Herein is Sally's specific dilemma: does he force Berger to work and produce or does he let "his" men be executed?

A contrast comes in the person of Adolf Berger (August Diehl), an idealistic prisoner working in the dark room, who has lost his family in other concentration camps. He wants to fight back in any way possible. And the best way he can is to sabotage the negatives of the fake pounds. By stalling these counterfeiting efforts he is fighting the enemy. So while Sally is actively working with the Germans to keep his life, Berger is only ostensibly working with them while actually working against them. When Herzog realizes things are not on track he makes it clear: produce results or targeted men will die. Herein is Sally's specific dilemma: does he force Berger to work and produce or does he let "his" men be executed?

McDormand (Fargo, The Man Who Wasn't There, Miller's Crossing), has a central role as Linda Litzke, a supervisor at the gym. She is a lonely woman, searching the on-line dating agencies for a date or a mate. Then there's John Malkovich playing foul-mouthed CIA analyst Osbourne Cox. Tilda Swinton is his wife, Katie Cox, a cold-hearted self-centered pediatrician with the bedside manner of a witch. Come to think of it, she played this role in The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe, although not married there. But the creme-de-la-creme is Brad Pitt, in an outrageous hairdo, as Chad Feldheimer, a personal trainer at the gym and friend to Linda. He is fabulously funny as a person who simply does not know how stupid he is. With the exception of Swinton, the writer-directors had all these particular actors in mind for the lead characters as they were developing their script. And it shows, in how well they work together.

McDormand (Fargo, The Man Who Wasn't There, Miller's Crossing), has a central role as Linda Litzke, a supervisor at the gym. She is a lonely woman, searching the on-line dating agencies for a date or a mate. Then there's John Malkovich playing foul-mouthed CIA analyst Osbourne Cox. Tilda Swinton is his wife, Katie Cox, a cold-hearted self-centered pediatrician with the bedside manner of a witch. Come to think of it, she played this role in The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe, although not married there. But the creme-de-la-creme is Brad Pitt, in an outrageous hairdo, as Chad Feldheimer, a personal trainer at the gym and friend to Linda. He is fabulously funny as a person who simply does not know how stupid he is. With the exception of Swinton, the writer-directors had all these particular actors in mind for the lead characters as they were developing their script. And it shows, in how well they work together. Katie inadvertently copies parts of this memoir, along with Osbourne's financial portfolio, onto a CD, and this enigmatic CD is found in the locker room at Hardbodies. Chad sees it as "sigint," signals intelligence, the kind of espionage material that you must "burn after reading." He and Linda see it as their meal ticket.

Katie inadvertently copies parts of this memoir, along with Osbourne's financial portfolio, onto a CD, and this enigmatic CD is found in the locker room at Hardbodies. Chad sees it as "sigint," signals intelligence, the kind of espionage material that you must "burn after reading." He and Linda see it as their meal ticket. One of the plot motifs is idiocy. (The tag-line is: Intelligence is relative.) The two main "heroes," Chad and Linda, are morons. Their minds are simply too small to comprehend what they are doing and getting themselves into. Yet, the "intelligence officers" of the CIA, along with Harry, the State Department Marshall, are dimwitted. They do not know what is going on. These are the people we rely on to provide intelligence to the President and they are unknowing fools. The only two characters with any form of intelligence are Osbourne and Ted. Yet, Osbourne, catching Ted in an unwise act, tells him, "You represent the idiocy of today . . . You are part of a league of morons. Oh, yes. You see you're one of the morons I've been fighting my whole life." He mistakes an act of love for an act of lunacy.

One of the plot motifs is idiocy. (The tag-line is: Intelligence is relative.) The two main "heroes," Chad and Linda, are morons. Their minds are simply too small to comprehend what they are doing and getting themselves into. Yet, the "intelligence officers" of the CIA, along with Harry, the State Department Marshall, are dimwitted. They do not know what is going on. These are the people we rely on to provide intelligence to the President and they are unknowing fools. The only two characters with any form of intelligence are Osbourne and Ted. Yet, Osbourne, catching Ted in an unwise act, tells him, "You represent the idiocy of today . . . You are part of a league of morons. Oh, yes. You see you're one of the morons I've been fighting my whole life." He mistakes an act of love for an act of lunacy.

Back are the whole gang, Eric Idle, John Cleese, Michael Palin, Terry Jones and Graham Chapman. Each plays multiple roles, including female characters. In particular, Chapman stars as Brian Cohen and Jones plays his mom, the non-virgin Mandy.

Back are the whole gang, Eric Idle, John Cleese, Michael Palin, Terry Jones and Graham Chapman. Each plays multiple roles, including female characters. In particular, Chapman stars as Brian Cohen and Jones plays his mom, the non-virgin Mandy. Life of Brian, shot on the some of the same sets as Zeferelli's Jesus of Nazareth, does give a picture of what life might have been like for followers of Jesus. As Brian inadvertently was seen as the Savior, people flocked to him. "I'm not the Messiah! Will you please listen to me? I am not the Messiah, do you understand? Honestly!" But even against his wishes, they said, "Only the true Messiah denies His divinity." And Brian is put into a quandary. Even his mother says, "He's not the Messiah! He's a very naughty boy!" The film makes it clear that Brian is not the Savior. He does not want to be followed by these folks. Even when he accidentally loses a sandal, they think he has given them a sign, like foot-washing (John 13:17).

Life of Brian, shot on the some of the same sets as Zeferelli's Jesus of Nazareth, does give a picture of what life might have been like for followers of Jesus. As Brian inadvertently was seen as the Savior, people flocked to him. "I'm not the Messiah! Will you please listen to me? I am not the Messiah, do you understand? Honestly!" But even against his wishes, they said, "Only the true Messiah denies His divinity." And Brian is put into a quandary. Even his mother says, "He's not the Messiah! He's a very naughty boy!" The film makes it clear that Brian is not the Savior. He does not want to be followed by these folks. Even when he accidentally loses a sandal, they think he has given them a sign, like foot-washing (John 13:17). Life of Brian falters a little toward the end, with some extended skits. But it closes with a bang. With over 100 criminals crucified on Passover, one (Eric Idle) leads them in a song, encouraging the dying to "always look on the bright side of life." Whistling while dying, they all join in on this finale. And it is good advice, even biblical advice (Phil. 4:8). As followers of Jesus, we are to be optimistic, even in the face of death. Death can kill our physical bodies but not our souls. Whether on the cross or on our life's course, our attitude will determine our response to circumstances. Maintaining a good attitude, focusing on what is good and right, and looking on the bright side of life will help us stay the course.

Life of Brian falters a little toward the end, with some extended skits. But it closes with a bang. With over 100 criminals crucified on Passover, one (Eric Idle) leads them in a song, encouraging the dying to "always look on the bright side of life." Whistling while dying, they all join in on this finale. And it is good advice, even biblical advice (Phil. 4:8). As followers of Jesus, we are to be optimistic, even in the face of death. Death can kill our physical bodies but not our souls. Whether on the cross or on our life's course, our attitude will determine our response to circumstances. Maintaining a good attitude, focusing on what is good and right, and looking on the bright side of life will help us stay the course.

Cut to Constable McGahan. Disoriented, he collapses at the foot of an escalator, dizzy from a hearing problem. Diagnosed to be tinnitus, he is given a doctor's note and expects to be put on medical leave. But he is sorely disappointed. His superior ignores the note and instead of sick leave McGahan is sent to serve caravan duty.

Cut to Constable McGahan. Disoriented, he collapses at the foot of an escalator, dizzy from a hearing problem. Diagnosed to be tinnitus, he is given a doctor's note and expects to be put on medical leave. But he is sorely disappointed. His superior ignores the note and instead of sick leave McGahan is sent to serve caravan duty. When Lavinia's photo turns up with a slogan spray-painted on it, the detectives won't tell her what it says. They are simply focused on the case, not worrying about the impacts on the victim. As the two narrative stories reach confluence, she asks McGahan to tell her what it says. She wants the truth, not some cockamamie platitude. Sensing her pain, he goes against police protocol and tells her.

When Lavinia's photo turns up with a slogan spray-painted on it, the detectives won't tell her what it says. They are simply focused on the case, not worrying about the impacts on the victim. As the two narrative stories reach confluence, she asks McGahan to tell her what it says. She wants the truth, not some cockamamie platitude. Sensing her pain, he goes against police protocol and tells her.

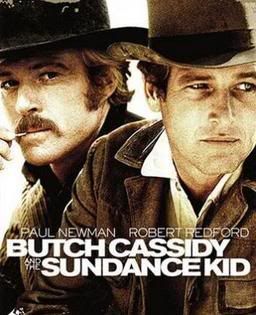

Butch Cassidy is not as much fun as I remembered, when I saw it decades ago for the first time. It certainly has great chemistry between the two stars. Indeed, this was the first of only two films featuring Newman and Redford. (The second, The Sting, was a better film with a superior screenplay and plot.) But it is drawn out and gets slow and tedious towards the end. Even the banter between Butch and Sundance, along with their female friend, Etta Place (Katherine Ross), gets tiresome.

Butch Cassidy is not as much fun as I remembered, when I saw it decades ago for the first time. It certainly has great chemistry between the two stars. Indeed, this was the first of only two films featuring Newman and Redford. (The second, The Sting, was a better film with a superior screenplay and plot.) But it is drawn out and gets slow and tedious towards the end. Even the banter between Butch and Sundance, along with their female friend, Etta Place (Katherine Ross), gets tiresome. When Butch, Sundance and Etts sail for Bolivia in South America, they think they are leaving behind all their problems. But new ones emerge and old ones pursue. The langauage is a barrier and it is fun to see Etta teach the two scoundrels "robbing-bank" phrases in Spanish. As they return to their old ways, they start to build up a notorious reputation as the "Yanqui Bandidos". The leader of the posse, too, shows up, still looking for Butch and Sundance.

When Butch, Sundance and Etts sail for Bolivia in South America, they think they are leaving behind all their problems. But new ones emerge and old ones pursue. The langauage is a barrier and it is fun to see Etta teach the two scoundrels "robbing-bank" phrases in Spanish. As they return to their old ways, they start to build up a notorious reputation as the "Yanqui Bandidos". The leader of the posse, too, shows up, still looking for Butch and Sundance. Whatever they thought of themselves, they were anachronistic law-breakers. Their crimes would catch up with them. They would pay with their lives.

Whatever they thought of themselves, they were anachronistic law-breakers. Their crimes would catch up with them. They would pay with their lives.

Keeping to himself, he quickly runs up against Dragline (George Kennedy), the unofficial leader of the chain gang. Determined to teach him a lesson, Dragline takes him on in the Saturday boxing fight. Beaten senseless, Luke keeps on getting up. What started as entertainment for the men and a form of humiliation for Luke, winds up being painful for everyone. They all want the beating to end. Even Dragline tells Luke, "Stay down. You're beat." But Luke responds, "You're gonna hafta kill me." Dragline leaves him punch-drunk, wandering on legs of jelly. Yet, this kind of determination earns a prisoner respect. And in a poker game later, Luke earns the friendship of Dragline and his prison moniker: "Cool Hand Luke."

Keeping to himself, he quickly runs up against Dragline (George Kennedy), the unofficial leader of the chain gang. Determined to teach him a lesson, Dragline takes him on in the Saturday boxing fight. Beaten senseless, Luke keeps on getting up. What started as entertainment for the men and a form of humiliation for Luke, winds up being painful for everyone. They all want the beating to end. Even Dragline tells Luke, "Stay down. You're beat." But Luke responds, "You're gonna hafta kill me." Dragline leaves him punch-drunk, wandering on legs of jelly. Yet, this kind of determination earns a prisoner respect. And in a poker game later, Luke earns the friendship of Dragline and his prison moniker: "Cool Hand Luke." To the men of the prison camp Luke is a leader, "a natural-born world shaker." But he does not want to be a leader. He has no plans, he lives moment to moment. He just wants to serve his time. He brings the unconventional to these men and gains their respect. But he also earns the eye of the bosses, the prison wardens, to whom he is a trouble-maker.

To the men of the prison camp Luke is a leader, "a natural-born world shaker." But he does not want to be a leader. He has no plans, he lives moment to moment. He just wants to serve his time. He brings the unconventional to these men and gains their respect. But he also earns the eye of the bosses, the prison wardens, to whom he is a trouble-maker. But Luke was an antihero. His was a life of breaking the rules, of doing what he felt like doing regardless of the cost. And this cost him his freedom. Jesus, on the other hand, is our true hero. He has given us some rules to follow. The two greatest commandments, he tells us, are to love our God and to love others as ourselves (Matt. 22:37-39). The rest of the Law, the Old Testament, can be summed up in these two (Matt. 22:40). He also gives us a new commandment, to love one another (John 13:34). The life Jesus wants us to live is not one that is overly constrained by a list of dos and don'ts. He wants us to be free, but within the constraints of love. We still need to live within society's rules. We cannot become anarchists or even iconoclasts like Luke. Instead, to live like Jesus is to experience real life, life to the full (John 10:10).

But Luke was an antihero. His was a life of breaking the rules, of doing what he felt like doing regardless of the cost. And this cost him his freedom. Jesus, on the other hand, is our true hero. He has given us some rules to follow. The two greatest commandments, he tells us, are to love our God and to love others as ourselves (Matt. 22:37-39). The rest of the Law, the Old Testament, can be summed up in these two (Matt. 22:40). He also gives us a new commandment, to love one another (John 13:34). The life Jesus wants us to live is not one that is overly constrained by a list of dos and don'ts. He wants us to be free, but within the constraints of love. We still need to live within society's rules. We cannot become anarchists or even iconoclasts like Luke. Instead, to live like Jesus is to experience real life, life to the full (John 10:10).

Anderson carefully builds the tension slowly. The first act introduces the main characters. When Roy goes off with Carlos and never reboards the train there is an air of mystery; something sinister is afoot. This continues as Grinko embarks on the lookout for students or young people who are mules, running drugs for the Russian mob. When Carlos and Abby fail to get back on the train, Grinko becomes their new compartment occupant. He is the last person Jessie wants in her cabin. This deepens the plot and adds a further threatening element to her demons.

Anderson carefully builds the tension slowly. The first act introduces the main characters. When Roy goes off with Carlos and never reboards the train there is an air of mystery; something sinister is afoot. This continues as Grinko embarks on the lookout for students or young people who are mules, running drugs for the Russian mob. When Carlos and Abby fail to get back on the train, Grinko becomes their new compartment occupant. He is the last person Jessie wants in her cabin. This deepens the plot and adds a further threatening element to her demons. One problem with Transsiberian is that it becomes contrived, even preposterous, as it moves towards its climax. And Jessie's character crumbles under pressure. Yet, the tension keeps us engaged. There is a scene of gruesome torture that is hard to watch, but conveys the seriousness of the situation that Jessie finds herself in. And it is her camera that plays a key role in bringing resolution to the film. As she hid behind her camera, seeing the world through its lens, so the world can see what she sees. And captured on digital film, it provides evidence for and against her.

One problem with Transsiberian is that it becomes contrived, even preposterous, as it moves towards its climax. And Jessie's character crumbles under pressure. Yet, the tension keeps us engaged. There is a scene of gruesome torture that is hard to watch, but conveys the seriousness of the situation that Jessie finds herself in. And it is her camera that plays a key role in bringing resolution to the film. As she hid behind her camera, seeing the world through its lens, so the world can see what she sees. And captured on digital film, it provides evidence for and against her.

At the start of the film, Banner is working in Brazil. When Gen. Ross finds evidence of him there, he sends a team of soldiers to capture him led by Emil Blonsky (Tim Roth). Of course, things go awry in the carefully planned take-down. The night-time chase sequence across the roof-tops and into the deserted bottling plant is a action-packed opening. But when Banner is trapped his pulse rises and the Hulk comes alive.

At the start of the film, Banner is working in Brazil. When Gen. Ross finds evidence of him there, he sends a team of soldiers to capture him led by Emil Blonsky (Tim Roth). Of course, things go awry in the carefully planned take-down. The night-time chase sequence across the roof-tops and into the deserted bottling plant is a action-packed opening. But when Banner is trapped his pulse rises and the Hulk comes alive. When Banner returns to the US to seek out a cure he returns to the university where Betty works. Of course, he is reunited to her, his one true love. But this sets the scene for the second Hulk sequence, when Gen. Ross once again sends in Blonsky and men to capture him. This time, Blonsky has had some modifications of his own to become stronger. But he is still not strong enough. Again, the Hulk escapes, this time with Betty who sees Banner's alter ego up close and personal.

When Banner returns to the US to seek out a cure he returns to the university where Betty works. Of course, he is reunited to her, his one true love. But this sets the scene for the second Hulk sequence, when Gen. Ross once again sends in Blonsky and men to capture him. This time, Blonsky has had some modifications of his own to become stronger. But he is still not strong enough. Again, the Hulk escapes, this time with Betty who sees Banner's alter ego up close and personal. The scenes of Banner changing into the Hulk are clever, particularly showing the painful inner metamorphosis. Norton communicates the pain, both physical and emotional, in this transformation, but the resultant character is disappointing. He just looks too fake.

The scenes of Banner changing into the Hulk are clever, particularly showing the painful inner metamorphosis. Norton communicates the pain, both physical and emotional, in this transformation, but the resultant character is disappointing. He just looks too fake. Banner finally meets up with a scientist helping him find a cure, Dr Stearns (Tim Blake Nelson) in New York. When Banner is captured, Blonsky tells Stearns: "I want more. You've seen what he becomes, right?" Stearns replies, "I have. And it's beautiful. Godlike." The aggressive Blonsky comes back, "Well, I want that. I need that. Make me that." And Stearns does. But what he creates is not another Hulk, but The Abomination, a larger, meaner, more aggressive creature. The finale sets up an extended fight sequence between The Abomination and The Hulk.

Banner finally meets up with a scientist helping him find a cure, Dr Stearns (Tim Blake Nelson) in New York. When Banner is captured, Blonsky tells Stearns: "I want more. You've seen what he becomes, right?" Stearns replies, "I have. And it's beautiful. Godlike." The aggressive Blonsky comes back, "Well, I want that. I need that. Make me that." And Stearns does. But what he creates is not another Hulk, but The Abomination, a larger, meaner, more aggressive creature. The finale sets up an extended fight sequence between The Abomination and The Hulk. Like the climax to Iron Man, we see two larger than life characters duking it out while a frightened populace runs and hides. However, in Iron Man Stark is fighting Stane in a conscious battle of good versus evil. Here, the Hulk has very limited mental ability. Banner's thoughts and memories are clouded by the anger and fury. So in this final fight, it is more one of might vs more might than good vs evil.

Like the climax to Iron Man, we see two larger than life characters duking it out while a frightened populace runs and hides. However, in Iron Man Stark is fighting Stane in a conscious battle of good versus evil. Here, the Hulk has very limited mental ability. Banner's thoughts and memories are clouded by the anger and fury. So in this final fight, it is more one of might vs more might than good vs evil.

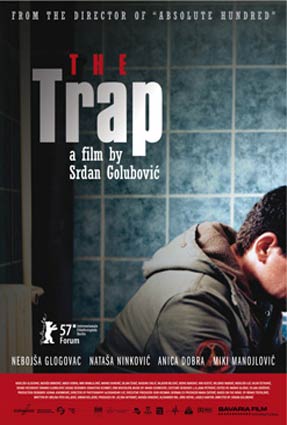

The Trap shows the huge divide between the wealthy and the workers in Serbia, a country in transition, struggling to find itself. Mladen is one of the workers. When Marija, a teacher, agrees to privately tutor one of her students, she sees the divide first-hand. The student's home has a picture frame that costs more than the surgery her son needs. Literally, this frame is worth more than his life. Post-war Belgrade is filled with such paradoxes.

The Trap shows the huge divide between the wealthy and the workers in Serbia, a country in transition, struggling to find itself. Mladen is one of the workers. When Marija, a teacher, agrees to privately tutor one of her students, she sees the divide first-hand. The student's home has a picture frame that costs more than the surgery her son needs. Literally, this frame is worth more than his life. Post-war Belgrade is filled with such paradoxes. The second scene has Mladen and Marija sitting in their old Renault at a red light in the pouring rain. As the wipers swish back and forth, the couple sit there silently. The traffic light, reflected in the surface water on the road, slowly turns from red to yellow to green and back to red. They are in no hurry. There is nowhere for them to go or to turn. They are in a sea of despair, alone yet together.

The second scene has Mladen and Marija sitting in their old Renault at a red light in the pouring rain. As the wipers swish back and forth, the couple sit there silently. The traffic light, reflected in the surface water on the road, slowly turns from red to yellow to green and back to red. They are in no hurry. There is nowhere for them to go or to turn. They are in a sea of despair, alone yet together. The Trap has some intriguing twists and turns along the way, especially as the victim's wife Jelena (Anica Dobra) comes onto the scene. Murdering a businessman is one thing. But he also has a wife and a child. Killing him leaves a widow and an orphan. Mladen can see the devastation that one bullet could cause.

The Trap has some intriguing twists and turns along the way, especially as the victim's wife Jelena (Anica Dobra) comes onto the scene. Murdering a businessman is one thing. But he also has a wife and a child. Killing him leaves a widow and an orphan. Mladen can see the devastation that one bullet could cause.