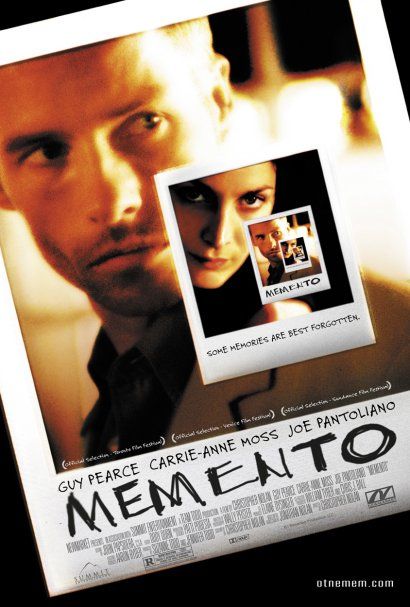

Director: Christopher Nolan, 2000.

Memento started out as an idea for a short story that Jonathan Nolan, Christopher's brother, was developing. When they discussed it on a road trip together, Christopher decided to create a screenplay for the film at the same time as his brother was writing his story, a story originally called "Memento Mori" -- which means remember death. That is perhaps a better title, as the story is about a man's attempt to remember his wife's death and then seek vengeance on the killer.

Nolan (Batman Begins, The Dark Knight) has created a complicated but highly intelligent and original brain teaser that keeps the viewer wondering what happened even as it ends. To do this, he interweaves two plotlines. The first is in color working backwards from the end. The other is in black and white in the present moving forwards .

The film opens with a scene of a man being killed at point blank range in an abandoned building. Leonard (Guy Pierce) is the killer but who has he killed and why? The opening tracks backward as the Polaroid photo he takes of his victim slowly fades and disappears. This is symbolic of Leonard's memories.

Leonard was an insurance investigator whose wife was raped and murdered during a burglary. He himself sustained a head injury that left him unable to make new memories. This is a real condition called anterograde amnesia occurring when the brain's hippocampus is damaged. Without short-term memory the sense of time disappears and the timing of events become indeterminate.

As he acts as his own private investigator, knowing little and remembering nothing, he comments: "Facts, not memories. That's how you investigate." He cannot rely on his memories as these are gone within minutes. Instead, he must rely on the "facts" and captures them with Polaroid photographs that he annotates or phrases he tatoos on his body.

As he acts as his own private investigator, knowing little and remembering nothing, he comments: "Facts, not memories. That's how you investigate." He cannot rely on his memories as these are gone within minutes. Instead, he must rely on the "facts" and captures them with Polaroid photographs that he annotates or phrases he tatoos on his body.So how do memories differ from facts? Leonard himself tells us, "Memory can change the shape of a room; it can change the color of a car. And memories can be distorted. They're just an interpretation. They're not a record, and they're irrelevant if you have the facts." It certainly is true that memory can alter perception. Take any two witnesses of an event and their account will not agree with each other 100%. Indeed, eye witness accounts are often the least reliable in a court of law due to this fact. Yet, in questioning the reliability of memory Nolan raises the topic of hermeneutics, or interpretation.

We try to remain objective in interpreting events (or books, even films). But subjectivity creeps in. We cannot keep it out. The worse our memory the more questionable our account of the event and hence our interpretation of it. This is clear in Memento. Even though Leonard records facts to help him remember, are these facts true or twisted? How much self-deception is there? This is a key theme in Memento and we will return to it later.

Nolan builds a sense of desperation into this psychological thriller. The viewer sees everything from Leonard's perspective. He puts us in his head and in so doing gives us a subjective and distorted point of view. He is trying to make the audience question their own process of memory. This becomes as confusing for us as it is for Leonard. Yet, all the true facts are there for all to see.

Memento includes the classic tropes of film noir: voice-over narration from the protagonist; a seductive and dangerous femme fatale Natalie (Carrie-Anne Moss, Trinity in The Matrix); a mysterious low-life/underworld character Teddy (Joe Pantoliano); several villains; and run-down locations. Yet this is clearly a postmodern film, one that could not have been made in the heyday of film noir. It has been described as nonlinear for its forward-backward scene interchanges, but Nolan argues that it is very linear, since each scene depends implicitly on its predecessor for the narrative to make sense. But for the plot to be understood, the whole must be seen and not just the parts. Memories and facts, seen out of context and disconnected, can lead to incorrect and deceptive conclusions.

Memento includes the classic tropes of film noir: voice-over narration from the protagonist; a seductive and dangerous femme fatale Natalie (Carrie-Anne Moss, Trinity in The Matrix); a mysterious low-life/underworld character Teddy (Joe Pantoliano); several villains; and run-down locations. Yet this is clearly a postmodern film, one that could not have been made in the heyday of film noir. It has been described as nonlinear for its forward-backward scene interchanges, but Nolan argues that it is very linear, since each scene depends implicitly on its predecessor for the narrative to make sense. But for the plot to be understood, the whole must be seen and not just the parts. Memories and facts, seen out of context and disconnected, can lead to incorrect and deceptive conclusions. And that brings us back to self-deception. Talking to Teddy, he says, "Will I lie to myself to be happy? . . . Yes, I will." Leonard knows his memory will fade and he will only remember the "facts" that he tatoos or photographs. He can easily deceive himself. Teddy retorts, "There's nothing wrong with that. We all do it." How true this is! We all do it to some degree or another. We deceive ourselves so we might ignore the truth. We pull the blinders over the eyes of our alleged objectivity and live in specious subjectivity.

And that brings us back to self-deception. Talking to Teddy, he says, "Will I lie to myself to be happy? . . . Yes, I will." Leonard knows his memory will fade and he will only remember the "facts" that he tatoos or photographs. He can easily deceive himself. Teddy retorts, "There's nothing wrong with that. We all do it." How true this is! We all do it to some degree or another. We deceive ourselves so we might ignore the truth. We pull the blinders over the eyes of our alleged objectivity and live in specious subjectivity.Craig Detweiler, in his book "Into the Dark," devotes the bulk of a chapter to analyzing this movie. In an honest and self-revealing comment, he agrees, "Don't I filter out selective memories in creating my own personal history? Don't I choose which facts to inscribe on my heart and mind (if not my body)?"

This self-deception is an attempt to recreate identity. Teddy tells Leonard, "You don't know who you are anymore," to which Leonard replies, "Of course I do." "No, that's who you were. Maybe it's time you started investigating yourself." There is a gap between who Leonard was and who he is. His identity has undergone a transformation. His self definition is dependent on his memory.

Like Leonard we use our memories to define ourselves. When we alter our memories in self-deception we are seeking to redefine who we are. But this does not change the essence of our being. So, who can we trust, if not ourselves? Friends like Teddy or Natalie? We need a community of close friends to reflect our personas to our eyes. Yet, even such a community can only offer us a clouded mirror (1 Cor. 13:12).

Like Leonard we use our memories to define ourselves. When we alter our memories in self-deception we are seeking to redefine who we are. But this does not change the essence of our being. So, who can we trust, if not ourselves? Friends like Teddy or Natalie? We need a community of close friends to reflect our personas to our eyes. Yet, even such a community can only offer us a clouded mirror (1 Cor. 13:12).What we really need is a totally trustworthy and reliable narrator who can speak truth to us. Where can we find such a person, an objective source? In Jesus. The Bible speaks to us honestly and bluntly. It is sharper than a sword (Heb. 4:12) and able to penetrate into the deepest recesses of our hearts. We are made in God's image (Gen. 1:26). Even if our memory fails, we still possess inherent dignity from this imago dei. Marred by the fall, we are remade by the sacrifice of Christ, who will help uncloud the darkness of our minds. Following him, we can begin to see clearly and avoid the dangers of self-deception.

Copyright ©2009, Martin Baggs

No comments:

Post a Comment