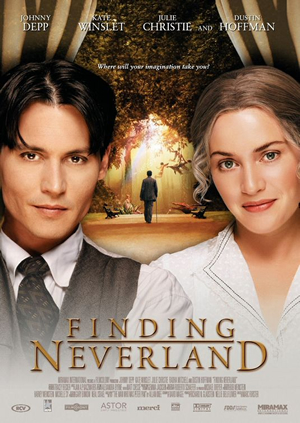

Director: Marc Forster, 2004.

"Grow up." "Act your age." "Quit being a kid." "Be a man." How many times have we heard people tell us one of these? Or maybe we have used them on our kids. They sound so mature and logical. But they fly in the face of the premise of this movie.

Finding Neverland takes us behind the scenes of "Peter Pan," telling the story that led to that play's creation. Though it is based on real life, some of the events are more imaginative or modified, such as the conflating of five Llewelyn Davies children into four. But surely a movie that extols imagination can be cut some inventive slack.

Johnny Depp (Chocolat) plays James M. Barrie, the Scottish playwright, with a marvelous brogue and a genuine sense of wonder. Coming off an opening night flop, Barrie is keen to create a play that will be a hit. But he has writer's block. His beautiful but distant wife Mary (Radha Mitchell) is no help. There is little love shared between the two. For them, appearance and proper behavior is paramount. After all, this is 1903 London, barely post-Victorian.

Enter Sylvia Llewelyn Davies (Kate Winslet) and her brood of kids. When Barrie is walking his dog in a London park, he meets Peter (Freddie Highmore), one of her sons. Peter and Barrie are foils to one another, at the very heart of the film. When Barrie invites Sylvia and her sons to sit and watch him put on a show, he entreats them to activate their childlike imaginations and turn his dog, Porthos, into a dancing bear. The initial interchange between Peter and Barrie set the tone for the film and defines a key theme.

Enter Sylvia Llewelyn Davies (Kate Winslet) and her brood of kids. When Barrie is walking his dog in a London park, he meets Peter (Freddie Highmore), one of her sons. Peter and Barrie are foils to one another, at the very heart of the film. When Barrie invites Sylvia and her sons to sit and watch him put on a show, he entreats them to activate their childlike imaginations and turn his dog, Porthos, into a dancing bear. The initial interchange between Peter and Barrie set the tone for the film and defines a key theme.When Peter says cynically, reclining on the green grass, "This is absurd. It's just a dog," Barrie retorts,"Just a dog? Just?" Offended, Barrie addresses his dog first and then Peter:

Porthos, don't listen! Porthos dreams of being a bear, and you want to shatter those dreams by saying he's just a dog? What a horrible candle-snuffing word. That's like saying, 'He can't climb that mountain, he's just a man,' or 'That's not a diamond, it's just a rock.' Just.Peter has suffered the loss of his father. (In real life, his father was alive when Barrie met them, but his death makes for a better narrative.) He has not processed his grief, and is not ready to embrace dreams that are fragile. He does not want them dashed, as were all his dreams for enjoying time with his dad.

How often do we quash other's dreams with this little word "just." We may put down our kids' goals and aspirations, suggesting they "be real" yet in the process put to death their imagination. Death by little words. Maybe we do this to ourselves with negative self-talk. "I am just a blog-writer," I might say. What I really want is to be an author, writing books that people enjoy and are transformed by. Yet that little word "just" diminishes my hopes and dreams until I settle for what is, instead of aspiring for what could be. Just. Jesus said with faith even as tiny as a mustard seed, as small as could be imagined, nothing would be impossible (Matt. 17:20).

Craig Detweiler, in his excellent book "Into the Dark," quotes another of Barrie's line from this early scene which lays out the film's central thesis: " 'With those eyes, my bonnie lad, I'm afraid you'll never see it. However, with a wee bit of imagination, I can turn around right now and see the great bear, Porthos.' Producer Richard Gladstein says, 'That line is really the quintessential part of the movie. . . . It's really about giving a child back his childhood." Imagining vs settling, growing up vs staying childlike, believing vs disbelieving, these are the antithetical pairs that focus the movie.

As Barrie develops a friendship with the Llewelyn Davies family, he grows more child-like even as Peter stoically remains adult-like. To almost each scene with the boys Barrie brings toys for his imaginative games. Sometimes he is a pirate taking captives, other times he is an Indian shooting cowboys. Yet as he grows closer to them, he grows more distant from his wife. And he draws the ire of Sylvia's pragmatic mother (Julie Christie). She is worried about how the appearance of a grown man acting like a child around a widow can impact the social and marital prospects, rather than being concerned for the boys' well-being. Straitlaced, she is great at social conformity and adept at quashing many dreams.

The whole concept of believing is highlighted in two other scenes. First, we see Barrie trying to show the boys how to fly a kite. When Michael, the youngest, tries the first time he fails and the other boys offer dream-quashing comments, "Oh, I told you this wasn't going to work!" and "I don't think he's fast enough." But the child-like Barrie speaks words of encouragement, calling for faith, "It's not going to work if no one believes in him!" Faith is what they needed.

The whole concept of believing is highlighted in two other scenes. First, we see Barrie trying to show the boys how to fly a kite. When Michael, the youngest, tries the first time he fails and the other boys offer dream-quashing comments, "Oh, I told you this wasn't going to work!" and "I don't think he's fast enough." But the child-like Barrie speaks words of encouragement, calling for faith, "It's not going to work if no one believes in him!" Faith is what they needed.Then, toward the end of the film, when Sylvia lies ill in bed, Barrie uncharacteristically tells her, "They can see it, you know. You can't go on just pretending." (There's that just word again.) But she refutes this with passion: "Just pretending? You brought pretending into this family, James. You showed us we can change things by simply believing them to be different." And in a closing scene with Peter, Barrie pleads with the boy, "Just believe." And in a moment of magic that will cut through the most hardened heart, Peter finally believes, and lets his grief emerge with a single tear. The man has accepted responsibility and the boy has become a child.

Jesus has called us to become like little children if we wish to enter into his kingdom (Matt. 18:3). As we give up our own maturity and wisdom and once more look at life with eyes that can see the wonder of the dew drop on the rose petal or the beauty of the sunset over the Pacific, we learn to play again. We learn to laugh again. We can dream big dreams again. We can become a writer or an astronaut, a pro sports player or an actor.

Barrie's playing with the boys releases his own imagination. And from this emerges the ground-breaking concept of a playful play. At the time, plays were serious, not fantastic. But, drawing heavily from his times with the Llewelyn Davis family, he creates "Peter Pan," the story of a boy who would not grow up, and who goes to Neverland, the mythical place where we never grow old. And this would be his magnum opus.

Barrie's playing with the boys releases his own imagination. And from this emerges the ground-breaking concept of a playful play. At the time, plays were serious, not fantastic. But, drawing heavily from his times with the Llewelyn Davis family, he creates "Peter Pan," the story of a boy who would not grow up, and who goes to Neverland, the mythical place where we never grow old. And this would be his magnum opus.The contrast between growing up and staying childlike is captured in two crucial scenes. In one, George, another of the boys, realizes his mother is seriously ill. Watching his reaction, Barrie comments, "Magnificent. The boy is gone. In the last 30 seconds . . . you became a grown-up." Is this a compliment or a put-down? In perhaps the most poignant scene, Barrie finally opens up about Neverland. He has never told this to anyone, but he recounts to Sylvia how the death of his younger brother, when he himself was a child, traumatized his mother and left him in a perpetual child-like state. Evan as an adult, he has retreated from his responsibilities. He has continued to be a child. What a contrast to Peter, and even to George, two young boys who behave like middle-aged men.

Jesus once said if we have faith we can move mountains (Matt. 21:21). We have limited our faith with our adult reasoning. But if faith can save a man destined for hell (Eph. 2:8), if that faith can provide forgiveness of sins (Col. 1:14), all our sins past, present and future (Col. 2:13), that same faith can make us realize dreams we were too afraid even to tell our friends. It's time to give up growing up. It's time to play like a child. It's time to look at life through the eyes of our imaginations.

As nostalgic and mushy as it seems, Finding Neverland is a beautiful film, giving testament to the wonder of a child's imagination. And it points us to faith in a God who can change things.

Copyright ©2009, Martin Baggs

No comments:

Post a Comment