Director: Wes Anderson, 1996. (R)

What is the great American dream? And how do we attain it? Bottle Rocket explores these questions and more. But not in the ways we normally think of when we contemplate such concepts.

Most cult classics are the early work of a director or actor (think Blade Runner, Ridley Scott's third film, or The Rocky Horror Picture Show with Tim Curry in his first role). These films were often bombs when they came out but emerge over time as critical or even foundational in the auteur's philosophy. Bottle Rocket is one such classic and introduced the world to three Texans: Wes Anderson, and brothers Luke and Owen Wilson.

Originally made as a 13 minute black and white short, it was shown at the 1994 Sundance Festival and garnered attention, but more importantly money ($7M). This allowed Anderson and Owen Wilson, friends from the University of Texas, to write the longer script. But their longer film tanked at a screening causing them to be snubbed by Sundance and forcing them to rewrite the script, particularly the opening segment,.The final version is this quirky and off-beat comedy that some critics consider Anderson's best film, even though it was his debut.

We meet Anthony (Luke Wilson) in a mental institution. He is leaving, having spent time there voluntarily following exhaustion or a nervous breakdown. But instead of walking out the front door, he climbs down a rope-ladder made of bed-linens because his friend Dignan (Owen Wilson) believes he is helping to bust him out. Anthony does not want to burst Dignan's bubble!

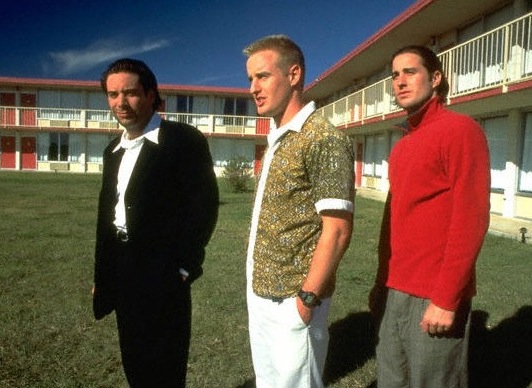

Dignan and Anthony are joined by their friend Bob (Robert Musgrave) as a trio of would-be criminals bent on a life of crime. Dignan is the "mastermind" and has plotted a crime spree that will put them on the map; or at least make them visible to local crime boss Mr. Henry (James Caan). If Dignan is the brains and Anthony is the brawn, Bob's main qualification is that he has a car and hence can be the getaway driver. These three low-life losers are striving to be gangsters; some might describe them as misfit mobsters.

Dignan and Anthony are joined by their friend Bob (Robert Musgrave) as a trio of would-be criminals bent on a life of crime. Dignan is the "mastermind" and has plotted a crime spree that will put them on the map; or at least make them visible to local crime boss Mr. Henry (James Caan). If Dignan is the brains and Anthony is the brawn, Bob's main qualification is that he has a car and hence can be the getaway driver. These three low-life losers are striving to be gangsters; some might describe them as misfit mobsters.The tagline says it all: they're not really criminals, but everybody's got to have a dream. Dignan is the only one who has a dream. And his great American dream is to become somebody, a criminal somebody. Unlike many who have supersized dreams, hopelessly unrealistic, his is small-sized, easily attainable. A poignant picture of the smallness of his dreams comes when he arrives on a motorcycle to persuade Dignan to join him in a final caper. This motorcycle is a mini-bike, barely big enough for him to ride on.

Yet Anderson offers a celebration of dreaming. Too often we lose our dreams in the cynical world of reality and adulthood. But this is not necessary. We can dream, big dreams as well as little dreams. We can venture after things that are within reach. These give us hope. And hope does not disappoint, it keeps us alive (Rom. 5:5).

To accomplish our dreams we need to plan. That is so true. An early scene makes this clear. As they "escape" the mental institution on a bus, Dignan shows Anthony his notebook full of plans. There are short-term plans and long-term plans. Then there are 50-year plans, and 75-year plans! He is totally confident in his capabilities. In actuality, though, he is a bumbling idiot, unable to execute a plan if his life depended on it. And his plans go wrong even from the start.

Planning and organization is critical to achieving our dreams. Jesus talked about making plans (Lk. 14:28). Yet plans must be flexible, quickly changed as the realities of life assail them. When we fail to plan, we plan to fail. But when we plan and hold rigidly to that plan, despite changing circumstances, we are also prone to fail. Both short and long-term plans are important, but we cannot predict what will happen from day to day. James, the biblical writer, addresses this, when he said: "Now listen, you who say, 'Today or tomorrow we will go to this or that city, spend a year there, carry on business and make money.' Why, you do not even know what will happen tomorrow" (Jas. 4:13-14). We must be willing to give up or modify our plans constantly.

The trio's crime-spree culminates, initially, in the robbery of a bookstore, always known to be a storehouse of treasures (though not necessarily monetary). As they go on the lam, they stop at a Texan roadside trailer to buy fireworks and bottle rockets. Fleeing quietly to avoid capture, they noisily set off these rockets from their car while they are driving!

The Bottle Rocket of the title is used as an effective double metaphor. First, it describes the kinetic energy of life. Like the rockets that explode in an instant of energetic excitement, showering the viewer with a colorful display that dissolves away, life is short yet filled with wonder. Life is viewed as a temporary, but colorful, attraction. Shakespeare put it this way, in Macbeth: "Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player that struts and frets his hour upon the stage and then is heard no more: it is a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing." The apostle James, continuing his thought mentioned above, said, "What is your life? You are a mist that appears for a little while and then vanishes" (Jas. 4:14). If this is true, then we need to make the most of the short span of time we have on this earth. In particular, we need to make sure we connect to the author of Life, so that our lives have meaning and purpose.

The second metaphoric use of the bottle rocket is the misfit's unwillingness to embrace adulthood. Fireworks are for kids. The heroes' desire to buy these rockets and let them off from their vehicle demonstrates their lack of responsibility and avoidance of growing up. They are still just boys in men's clothes. Their dangerous adventures belie their naiveté.

The second metaphoric use of the bottle rocket is the misfit's unwillingness to embrace adulthood. Fireworks are for kids. The heroes' desire to buy these rockets and let them off from their vehicle demonstrates their lack of responsibility and avoidance of growing up. They are still just boys in men's clothes. Their dangerous adventures belie their naiveté.

Indeed, both main characters are still locked up in childish or idiotic logic. During one theft, as the cops are on the way, Dignan points out, "They'll never catch me . . . because I'm @*#! innocent." Naive he is; morally innocent he is not. In the bookstore theft Dignan says to the store manager in a fit of bravado, "A bigger bag you idiot!" But the manager recognizes the kid inside, and says, "Don't call me an idiot, you punk" and Dignan sheepishly retorts, "Do you have a bigger bag for maps and atlases . . . sir?" His macho exterior is a front for his childlike nature within. And Anthony is bedeviled by the fear of failure, "Grace [his sister] thinks I'm a failure." Neither have yet grown up; both are clinging to the freedom of youthful irresponsibility.

Anderson's films (e.g., The Darjeeling Limited) are all about characters and their journey, and this first one is no different. The improbability of the crime spree and the consequent escapades all function to show off these three lovable characters. They are all searching for something, and they succeed in finding it. Yet for all of them, success comes in small sizes. Dignan finds direction and accomplishes his goal, although little and ludicrous. At the end he is satisfied with his lot, relishing his moment of glory, even forgiving the one who caused him grief (confer Jesus forgiving his crucifiers from the cross, Lk. 23:34). Anthony finds a woman to love. The motel-maid from Paraguay Inez (Lumi Cavazos, Like Water for Chocolate) not only brings joy to his life, she causes him to want to grow up and accept responsibility. And Bob gains respect from his brother (Andrew Wilson, yet another Wilson brother), who has bullied him for far too long.

Anderson's films (e.g., The Darjeeling Limited) are all about characters and their journey, and this first one is no different. The improbability of the crime spree and the consequent escapades all function to show off these three lovable characters. They are all searching for something, and they succeed in finding it. Yet for all of them, success comes in small sizes. Dignan finds direction and accomplishes his goal, although little and ludicrous. At the end he is satisfied with his lot, relishing his moment of glory, even forgiving the one who caused him grief (confer Jesus forgiving his crucifiers from the cross, Lk. 23:34). Anthony finds a woman to love. The motel-maid from Paraguay Inez (Lumi Cavazos, Like Water for Chocolate) not only brings joy to his life, she causes him to want to grow up and accept responsibility. And Bob gains respect from his brother (Andrew Wilson, yet another Wilson brother), who has bullied him for far too long.

Martin Scorsese was quoted in Esquire magazine, saying that this film is a "picture without a trace of cynicism that obviously grew out of its director's affection for his characters in particular and for people in general." We can appreciate this affection and laugh at these endearing small time hoods, yet at the same time cull lessons from their journey. Bottle rockets, anyone?

Copyright ©2010, Martin Baggs

Planning and organization is critical to achieving our dreams. Jesus talked about making plans (Lk. 14:28). Yet plans must be flexible, quickly changed as the realities of life assail them. When we fail to plan, we plan to fail. But when we plan and hold rigidly to that plan, despite changing circumstances, we are also prone to fail. Both short and long-term plans are important, but we cannot predict what will happen from day to day. James, the biblical writer, addresses this, when he said: "Now listen, you who say, 'Today or tomorrow we will go to this or that city, spend a year there, carry on business and make money.' Why, you do not even know what will happen tomorrow" (Jas. 4:13-14). We must be willing to give up or modify our plans constantly.

The trio's crime-spree culminates, initially, in the robbery of a bookstore, always known to be a storehouse of treasures (though not necessarily monetary). As they go on the lam, they stop at a Texan roadside trailer to buy fireworks and bottle rockets. Fleeing quietly to avoid capture, they noisily set off these rockets from their car while they are driving!

The Bottle Rocket of the title is used as an effective double metaphor. First, it describes the kinetic energy of life. Like the rockets that explode in an instant of energetic excitement, showering the viewer with a colorful display that dissolves away, life is short yet filled with wonder. Life is viewed as a temporary, but colorful, attraction. Shakespeare put it this way, in Macbeth: "Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player that struts and frets his hour upon the stage and then is heard no more: it is a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing." The apostle James, continuing his thought mentioned above, said, "What is your life? You are a mist that appears for a little while and then vanishes" (Jas. 4:14). If this is true, then we need to make the most of the short span of time we have on this earth. In particular, we need to make sure we connect to the author of Life, so that our lives have meaning and purpose.

The second metaphoric use of the bottle rocket is the misfit's unwillingness to embrace adulthood. Fireworks are for kids. The heroes' desire to buy these rockets and let them off from their vehicle demonstrates their lack of responsibility and avoidance of growing up. They are still just boys in men's clothes. Their dangerous adventures belie their naiveté.

The second metaphoric use of the bottle rocket is the misfit's unwillingness to embrace adulthood. Fireworks are for kids. The heroes' desire to buy these rockets and let them off from their vehicle demonstrates their lack of responsibility and avoidance of growing up. They are still just boys in men's clothes. Their dangerous adventures belie their naiveté.Indeed, both main characters are still locked up in childish or idiotic logic. During one theft, as the cops are on the way, Dignan points out, "They'll never catch me . . . because I'm @*#! innocent." Naive he is; morally innocent he is not. In the bookstore theft Dignan says to the store manager in a fit of bravado, "A bigger bag you idiot!" But the manager recognizes the kid inside, and says, "Don't call me an idiot, you punk" and Dignan sheepishly retorts, "Do you have a bigger bag for maps and atlases . . . sir?" His macho exterior is a front for his childlike nature within. And Anthony is bedeviled by the fear of failure, "Grace [his sister] thinks I'm a failure." Neither have yet grown up; both are clinging to the freedom of youthful irresponsibility.

Anderson's films (e.g., The Darjeeling Limited) are all about characters and their journey, and this first one is no different. The improbability of the crime spree and the consequent escapades all function to show off these three lovable characters. They are all searching for something, and they succeed in finding it. Yet for all of them, success comes in small sizes. Dignan finds direction and accomplishes his goal, although little and ludicrous. At the end he is satisfied with his lot, relishing his moment of glory, even forgiving the one who caused him grief (confer Jesus forgiving his crucifiers from the cross, Lk. 23:34). Anthony finds a woman to love. The motel-maid from Paraguay Inez (Lumi Cavazos, Like Water for Chocolate) not only brings joy to his life, she causes him to want to grow up and accept responsibility. And Bob gains respect from his brother (Andrew Wilson, yet another Wilson brother), who has bullied him for far too long.

Anderson's films (e.g., The Darjeeling Limited) are all about characters and their journey, and this first one is no different. The improbability of the crime spree and the consequent escapades all function to show off these three lovable characters. They are all searching for something, and they succeed in finding it. Yet for all of them, success comes in small sizes. Dignan finds direction and accomplishes his goal, although little and ludicrous. At the end he is satisfied with his lot, relishing his moment of glory, even forgiving the one who caused him grief (confer Jesus forgiving his crucifiers from the cross, Lk. 23:34). Anthony finds a woman to love. The motel-maid from Paraguay Inez (Lumi Cavazos, Like Water for Chocolate) not only brings joy to his life, she causes him to want to grow up and accept responsibility. And Bob gains respect from his brother (Andrew Wilson, yet another Wilson brother), who has bullied him for far too long.Martin Scorsese was quoted in Esquire magazine, saying that this film is a "picture without a trace of cynicism that obviously grew out of its director's affection for his characters in particular and for people in general." We can appreciate this affection and laugh at these endearing small time hoods, yet at the same time cull lessons from their journey. Bottle rockets, anyone?

Copyright ©2010, Martin Baggs

No comments:

Post a Comment