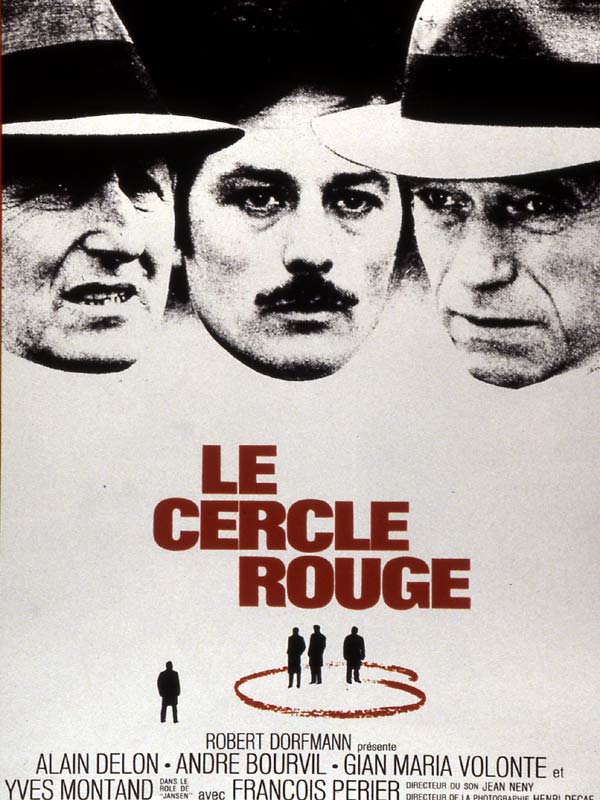

Director: Jean-Pierre Melville, 1970. (NR)

If you were asked to name the greatest heists movies of all time, what films would come to mind? Maybe Heat or The Italian Job. Probably Oceans 11. You’d likely not include Le Cercle Rouge; you’ve probably not even seen it. But it is quite possibly the greatest French heist film.

As French films go, this is long and languid. The first hour is spent developing character, tone and atmosphere, without especially advancing the plot. It is only in the second hour of this 140 minute movie, that the heist is planned and executed.

There are four key characters, three introduced in the first act. Noteworthy is the absence of any female roles. This is a masculine movie set in a man’s world.

Corey (Alain Delon) is the first character. A suave, mustachioed criminal, he is about to be released from prison after five years. Before gaining his freedom, a crooked guard presses him to commit the perfect crime: robbing a Parisian jewelry store. On the day he is released, he confronts and robs a former friend and criminal, then buys a car.

That same day, criminal suspect Vogel (Gian Maria Volonte) is being transported by train to be indicted and face justice. Handcuffed to his sleeper-cabin bed, he manages to pick the lock, jump through the window and flee into the wintry fields. Inspector Mattei (Andre Bourvil in his final performance), who had been accompanying him, sets a massive manhunt in place, but to no avail. Plodding and patient, he pursues Vogel through the film, being its only positive presence. He is the one who hears and challenges the moral of the movie. But we’ll come back to that.

That same day, criminal suspect Vogel (Gian Maria Volonte) is being transported by train to be indicted and face justice. Handcuffed to his sleeper-cabin bed, he manages to pick the lock, jump through the window and flee into the wintry fields. Inspector Mattei (Andre Bourvil in his final performance), who had been accompanying him, sets a massive manhunt in place, but to no avail. Plodding and patient, he pursues Vogel through the film, being its only positive presence. He is the one who hears and challenges the moral of the movie. But we’ll come back to that.The apparent philosophical meaning of the title, The Red Circle, is that those who are meant to meet will meet in this circle. And Vogel is meant to meet Corey. When he hides in Corey’s trunk, their meeting is destined to happen. Through a lucky break, Corey manages to get through the police roadblock. Chance, then brings these two criminals together. And they agree to commit the heist. Needing a third team member, a marksman, they call on an acquaintance of Vogel’s: Jansen (Yves Montand), an ex-police marksman, who is now an alcoholic. This is the trio that will hit the store.

After the lengthy prelude to the heist, writer-director Melville makes a stunning choice to shoot the robbery in almost real-time. The heist takes up almost half an hour, during which there is no dialog or background music. It is virtually silent, adding to the growing tension. This surely stands as one of the finest robberies in screen history.

Yet for all this, Le Cercle Rouge is like a French film noir sans the femme fatale. It is a world of moral darkness, with little hope. The key theme is stated by the police chief: “All men are guilty. They’re born innocent but it doesn’t last.” As if the viewer might miss this, he later repeats it to Mattei directly, “And don’t forget. All guilty.” The cop responds with a question: “Even policeman?” But the chief is clear: “All men, Mr. Mattei.”

Here, then, are the themes: guilt and innocence. And here are two questions to consider: are all people guilty? And are all people born innocent?

Here, then, are the themes: guilt and innocence. And here are two questions to consider: are all people guilty? And are all people born innocent?With respect to the first question, the Bible is clear: “For we have already made the charge that Jews and Gentiles alike are all under the power of sin. As it is written: ‘There is no one righteous, not even one;’“ (Rom. 3:9-10). We would like to consider ourselves pure and righteous and good. But this is not so. Paul goes on, “all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God” (Rom. 3:23). Our guilt condemns us before the judgment seat of God. None is innocent at this bar.

But were we innocent at birth and since we fallen from this state? Again, the Bible answers this question with clarity and specificity. King David, in one of his most famous psalms says, “Surely I was sinful at birth, sinful from the time my mother conceived me” (Psa. 51:5). Sadly, we have inherited the nature of sin from our original father, Adam (Gen. 3:6). At birth we emerge from the womb with a corrupt nature (Jer. 17:9). Like Melville’s vision, we are desperately dark and depraved. The world is a harsh place.

Unlike Le Cercle Rouge, though, we are destined to meet Jesus in the red circle, the circle of his blood. He shed his blood (Rom. 3:25), giving up his life, to pay the debt of our sin. When we meet him and fall at his feet as followers, he gives us a new nature (2 Cor. 5:17) and a second chance at life. We are not destined to be criminals forever like Corey or Vogel. We can be clothed in the righteousness of Christ (Gal. 3:27). But we must accept and embrace Christ. Only in his red circle will we find hope and life.

Copyright ©2011, Martin Baggs

No comments:

Post a Comment