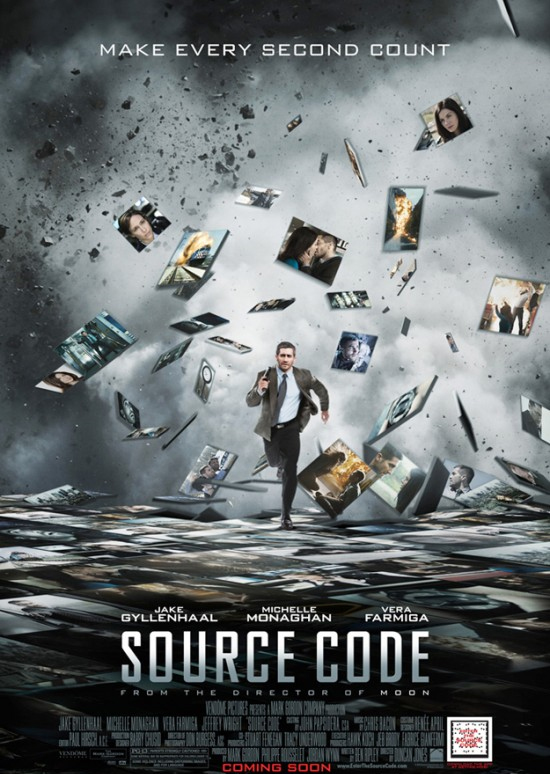

Director: Duncan Jones, 2011. (PG-13)

Source Code is a science fiction film set in an alternate present that crosses Groundhog Day with Memento (or possibly Avatar), resulting in a thriller that is intriguing at times and frustrating at others, especially the end which some love and others hate. Jones’ second movie, like his first (Moon), focuses on an isolated person and delves into themes of identity and memory. Unlike Moon, though, Source Code clearly has a bigger budget and more extensive cast.

The film begins as Captain Colter Stevens (Jake Gyllenhaal, Brothers), a US Air Force helicopter pilot, wakes to find himself on a commuter train bound for Chicago. Opposite him sits Christina (Michelle Monaghan), a pretty woman who is in the middle of a conversation with him. But Stevens doesn’t know her and isn’t who she thinks he is. He has somehow assumed the identity of another man. Confused, Stevens sees the array of passengers and cannot understand what is happening until 8 minutes later a bomb explodes and all aboard are killed.

Instead of dying, Stevens comes awake in a pod-like structure where he is strapped into a chair. With his last memory of a mission in Afghanistan, he is disoriented. His only source of contact is a military officer, Colleen Goodwin (Vera Farmiga, Up in the Air). Speaking to him through a video display, she tells him to focus on his mission, which is to find the bomb and the identity of the bomber on the train. She is single-minded and won’t address his concerns about memory or his desire to speak to his father. Instead she hits a button and sends him back into the train, once more picking up at the beginning. This time, though, he remembers what she has told him and recalls some of what happened in the earlier segment. Knowing that, he can change his approach.

Memory and identity. Is Steven’s identity defined by his memory? If he inhabits someone else’s memory does this change his identity? For Christina, this seems to be true. She sees Stevens as another person and interacts with him as such. But is our identity defined by memory? Or is it broader than that, with memory being just a piece of the puzzle?

Memory and identity. Is Steven’s identity defined by his memory? If he inhabits someone else’s memory does this change his identity? For Christina, this seems to be true. She sees Stevens as another person and interacts with him as such. But is our identity defined by memory? Or is it broader than that, with memory being just a piece of the puzzle?Obviously if identity is synonymous with memory, then amnesiacs and Altzheimer’s patients have lost their identity. But true identity is not displaced quite so easily. If we have chosen to follow Jesus, his promise is to bring us into his kingdom for an eternity of life after death (Jn. 14:2). Such a promise cannot be broken by physical or mental damage in this earthly life. If so, God’s promises would be fragile and faulty, something potentially lost. But that is not what Scripture communicates: “For no matter how many promises God has made, they are “Yes” in Christ” (2 Cor. 1:20). So, even if memory is damaged or lost, God still remembers who we are and in the spiritual realm and the hereafter we will retain our unique identity. Memory will be restored to us in that wonderful place (Rev. 21:4).

Instead, identity is defined by relationship. I am the son of my parents, bearing their name. I carry their genes and have characteristics that come from them. This is the identity we are born with. We also have a new identity, one that comes from a choice to relate positively to God through Jesus Christ. We can become children of God (Jn. 1:12), uniquely defined in this new relationship. Then we find our identity in our new father, and have the image of Jesus progressively manifested in us as we grow more and more into his likeness over time (Rom. 8:29, 2 Cor. 3;18).

Instead, identity is defined by relationship. I am the son of my parents, bearing their name. I carry their genes and have characteristics that come from them. This is the identity we are born with. We also have a new identity, one that comes from a choice to relate positively to God through Jesus Christ. We can become children of God (Jn. 1:12), uniquely defined in this new relationship. Then we find our identity in our new father, and have the image of Jesus progressively manifested in us as we grow more and more into his likeness over time (Rom. 8:29, 2 Cor. 3;18).As in Groundhog Day, Stevens finds himself being sent back to the same 8 minutes of the train journey for the mission described by Goodwin, as well as the mysterious Dr Rutledge (Jeffrey Wright) who stands behind her in the video frame. Each time, the scene plays out differently as Stevens begins to make choices that depart from his instructions.

The second theme that emerges is that of consent. Stevens is ordered to fulfill his mission, but it is not clear that he has given his consent to this. Though he is a military officer, he seems to be imprisoned in this pod without knowledge of the project he is involved with. Is it right, therefore, that he should be subjected to these multiple deaths if he wishes not to be sent back? Does his military enrollment allow his superiors to order him into this strange scenario without giving him any basic briefing?

We tend to assume that as human beings we have right to choice, that we cannot be held against our will and forced to play a part in such a disturbing drama. Even under a “need to know” banner, the military tend to give the troops enough information to enable success in the mission. Stevens, though, is clearly being held without his consent and possibly against his will. Since this is denying freedom of choice, it is ethically wrong. And as the movie plays out, this becomes clear. Unless we commit a crime, we have the right (at least in the United States), to liberty. Consent is indeed a civil liberty.

Jones does a good job of pacing, slowly revealing information with each new 8 minutes of Stevens’ train ride, enabling the viewer to solve the puzzle. Yet he retains a twist or two for the end. He also gets fair performances out of his cast. Gyllenhaal is a sympathetic hero, a man who moves from confused to concerned with a growing interest in Christina. Monaghan does what she can with a character who has no backstory.

The final theme centers on changing the past. Even though Goodwin tells him, “The program wasn’t designed to alter the past. It was designed to affect the future,” Stevens becomes more and more fixated on saving the passengers on the train, especially Christina. He thinks of the past even as Goodwin looks to the future.

This raises an interesting question: if you could change something in the past, would you? And if so, what would it be? To go along with the premise of the film, if you could go back 8 minutes in your life, is there one scene you would return to and make changes that would alter the trajectory of your life and those around you? If you answer yes, you probably carry some regret for mistakes made. Yet, we need to forgive ourselves for these, knowing God has already forgiven us (Eph. 1:7), and move on in the knowledge that we cannot go back and make such changes. Source Code is science fiction so allows for time reassignment; real life is linear. Maybe we should be thankful for that!

Copyright©2011, Martin Baggs