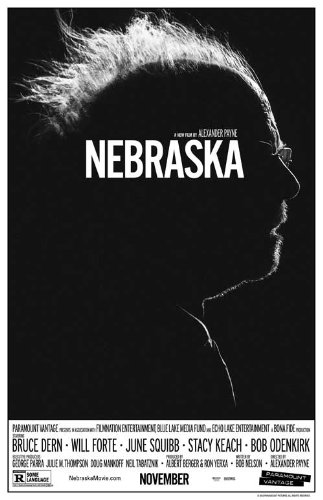

Director: Alexander Payne, 2013 (R)

An old man walks slowly down a main street in Billings Montana.

When pulled over by a friendly police officer, the man tells him he is walking

to Lincoln, Nebraska. Why? Because he has won a million dollars and needs to

get there to claim his winnings.

Woody Grant (Bruce Dern) can no longer drive and has resolved

to get to Nebraska by foot of he has to. Having received a scam letter from a

magazine publisher, his family tells him he is wasting his time but Woody

believes the letter. As his son says in one scene, “he just believes what

people tell him.” But his lifelong alcoholism has contributed to his apparent

sporadic dementia. Despite periods of lucidity, he drifts out of it for other

periods and his conversational reticence make it difficult to know which state

he is in.

When it is clear he won’t listen or give up, despite the

harangues from his acerbic tongued wife Kate (June Squib) and his bitter elder

son Ross (Bob Odenkirk), his younger son

David (Will Forte), a home theater salesman, agrees to drive him there. Nebraska,

thus, becomes a father-son road-trip with an extended stop for a family reunion

of sorts in Hawthorne, Nebraska, where Woody grew up

From its opening scene of empty Billings streets to the

dying businesses in Hawthorne, it is clear that one theme of the film is aging

(and dying). The movie is shot in a beautiful but bleak black and white that

adds an older world feel that underscores this theme. The small town of

Hawthorne itself looks like a ghost town with barely any young residents. Such

dying, though a part of life, seems a sad destination.

While in Hawthorne, Woody lets it slip that he has won $1

million. Suddenly the old friends pop out of the woodwork, all with old debts

for Woody to repay. Vultures all, they are driven by greed, a desire to get a

guilt-induced handout from an old man.

While in Hawthorne, Woody lets it slip that he has won $1

million. Suddenly the old friends pop out of the woodwork, all with old debts

for Woody to repay. Vultures all, they are driven by greed, a desire to get a

guilt-induced handout from an old man.

Greed is a sin denounced by Jesus, one that the Pharisees

held close to their heart (Mt. 23:25). Jesus placed it in a list of vices that

included adultery, lust and malice (Mk. 7:22). Moreover, Paul considered the

love of money to be a root of all kinds of evil (1 Tim. 6:10).

Though Woody’s extended family and friends greedily latched

onto him for some of his “winnings,” Woody had different intentions for the

money. One character asked him what he would do with the money, and what the

first thing he would spend it on. His answer, and later explanation, tells a

different tale. It forces us to wonder, what would you do with a million

dollars? What would be the first thing

you buy? Would you use this windfall for self or others? What motivation would

drive how you use it?

When Woody and David meet the extended family in Hawthorne,

two cousins immediately mock them. The two road-trippers become the butt of

their jokes. Indeed, these cousins are funny in their own red-necked stupidity.

But when Ross and Kate arrive, and the extended family is together, the family

dysfunction emerges. Kate is a sharp truth-teller. This comes out most clearly

in a scene where the immediate family visits a cemetery. Kate gives a

commentary on those buried: “There’s Woody’s little sister, Rose. She was only

nineteen when she was killed in a car wreck near Wausa. What a whore! I liked

Rose, but my God, she was a slut. I’m just telling you the truth!”

In some ways, Nebraska

resembles August: Osage County. The

mothers in both films are caustic, using their sharp tongues as truth-tellers.

Both have extended families enjoying a dinner. And both show these extended

families dysfunctioning. But while Osage

County ends with the family self-destructing, Nebraska at least shows the immediate family surviving, even

laughing together in a later scene. Both films underscore the point that truth

must be spoken in the context of love (Eph. 4:15), else it becomes sharp and

divisive.

In some ways, Nebraska

resembles August: Osage County. The

mothers in both films are caustic, using their sharp tongues as truth-tellers.

Both have extended families enjoying a dinner. And both show these extended

families dysfunctioning. But while Osage

County ends with the family self-destructing, Nebraska at least shows the immediate family surviving, even

laughing together in a later scene. Both films underscore the point that truth

must be spoken in the context of love (Eph. 4:15), else it becomes sharp and

divisive.

Despite all this, Nebraska is a comic drama. While Osage

County’s comedy was dark, almost black, the humor here is a little lighter.

Payne paints a bittersweet tale filled with quiet poignant scenes. The movie

itself is slow with a soft score that resonates with the cinematography. Like

his earlier films (Sideways, About Schmidt, The Descendants) Payne takes his time and shows us the humorous ups

and downs of ordinary people living ordinary lives.

Ultimately, though, Nebraska is about more than just aging,

dignity and greed. It is about family, and in particular the father-son

relationship. David wants to get to know his cantankerous father before it is

too late. The road trip to Hawthorne does not reveal much, but the family,

friends and foes found there offer up secrets his father never shared. Further,

Woody’s family background highlights how his character has emerged and how his

upbringing affected his parenting.

David, himself, gives us a picture of son honoring his

father, an example of the fifth of the Ten Commandments documented by Moses

(Exod. 20:12). He willingly and patiently does what he has to do, even though

he sees the trip as a fool’s folly, to support his father. It cost him in time

and money. But it was worth it, especially in the final part of the trip. In one

scene toward the end, David allows Woody to drive. Woody’s eyes light up. His

dignity and self-esteem emerge, and he is present if only for the length of Main

Street.

Many might find this film too slow and the characters too

unpleasant. But don’t be put off by these aspects. The film has a heart and a

message. Money is not everything. Family relationships mean so much more. Even

as our parents are slowly aging and degenerating, we should treat them with the

dignity they deserve. There is more to their lives than we will ever know. We

can and must honor them while they are still with us. They will appreciate it,

and God will bless us for it. After all, as Paul pointed out, that commandment, “Honor

your father and mother,” was “the first commandment with a promise” (Eph. 6:2).

Copyright ©2014, Martin Baggs

.jpg)