Director: Vinko Bresan, 2003.

If a tree falls in the forest and there is no one around to hear it, does it actually make a sound? This is a common philosophical brain-teaser that may cause some to ponder. Witnesses raises a similar question. But more on that later.

Initially slow but ultimately satisfying, this Croatian film centers around a murder committed in a village on the front-line during the civil war of 1992. Even while the man is being shot, the father of one of the killers lies dead in a casket in the family home, watched over by his widow. When the police arrive the next day, the inspector treats it as a true crime, while most of the neighborhood see it as a war-time annoyance. After all, the victim was a smuggler and a loan shark . . . and a Serb to boot. They think he had it coming.

There is one complication for the three murderers, all Croatian soldiers: there was a witness in the house of the murdered man -- his young daughter. So they kidnapped her and threw her in a garage, not knowing what to do with her. The key question, then, is what to do with the witness?

There is one complication for the three murderers, all Croatian soldiers: there was a witness in the house of the murdered man -- his young daughter. So they kidnapped her and threw her in a garage, not knowing what to do with her. The key question, then, is what to do with the witness?Upon this simple premise, Bresnan has crafted a complex film. The key to its success is repetition. He takes us back over the scenes multiple times, each time showing us something new, something unexpected. He introduces new characters, who are related to the plot in ways we don't foresee. In this regard, Witnesses is similar to Vantage Point, a later film. However, where Vantage Point used this plot device effectively to build a taut thriller with plenty of action but little character growth, Witnesses uses it to develop characters. And these are complex characters communicated by an excellent cast of actors not seen in America.

When the mother calls in the mayor, essentially the small town patriarch, to seek counsel, he offers chilling advice: "That which was not seen was not done . . . No witnesses. None." We are back to the falling tree in the unpopulated forest. If the killers silence the witness, then there was no witness. And if there was no witness, there was no crime. Is it really that simple? Is silence golden?

When the mother calls in the mayor, essentially the small town patriarch, to seek counsel, he offers chilling advice: "That which was not seen was not done . . . No witnesses. None." We are back to the falling tree in the unpopulated forest. If the killers silence the witness, then there was no witness. And if there was no witness, there was no crime. Is it really that simple? Is silence golden?Committing a crime, especially murder, is a sin. Moses told the Israelites, "You shall not murder" (Exod. 20:13). This law has stood the test of time. It remains in the law books of all democracies. Committing another crime, another murder, does not cause the first to disappear, to vanish. It simply doubles the sin. It is illogical to think otherwise. The criminal mind may think we can sweep such sins and crimes under the carpet and no one will know, especially in a time of war, but God sees all and knows all (Job 34:21-22, Psa. 94:11). Nothing escapes his attention. He will call us to account for such sin. Only through the finished work of Jesus can we find forgiveness, even for the acts no one but God sees (Eph. 1:7).

Another issue raised by Witnesses is that of genocide, but it is the subtext for the main points. Killing of people groups based on ethnicity or religion is wrong. Peaceful coexistence between different ethnic groups is a high and worthy goal that should be pursued as much as possible. But the film does not explore this and so I will leave it for another review. (Although, this film was the recipient of the Peace Film Award at the Berlin International Film Festival.)

A broader question framed by Bresan is, who are witnesses? One of the killers, realizing his predicament, makes the statement, "We are all witnesses" before committing suicide in a violent manner. How are we all witnesses? To what are we all witnesses? In the context of the movie, the soldier seems to be pointing to the war and the atrocities occurring on a daily basis. The town, even the country, knew what was going on. They were all witnesses. They were the other trees in the forest. Yet none was speaking out, none was coming forth. Their voices were silent. Are we witnesses of crimes, of social injustices? Are we willing to speak out to see justice served? Or are we silent, and in our silence pretending that no injustice, no sin, no crime was done?

Finally, for those of who follow Jesus he has charged us to be his witnesses, to the ends of the world (Acts 1:8). In this sense, too, we are all witnesses. So, are we speaking out for Christ? Are we giving a witness to those around us, in our words and in our deeds? Or are we acting like these soldiers, doing what the mayor suggested, and staying silent? If we are doing so, we silence the voice of Jesus. Witnesses reminds us that we can choose to remain silent, fearful, and act as though nothing has happened between us and Jesus. Or we can be a witness for Jesus, giving voice for him who paid for our sins and those of the world on the tree. What kind of witness will you be?

Copyright ©2008, Martin Baggs

When his best friend Lynn Lockner (Kristin Scott Thomas) discovers her lover murdered, it is Carter who puts himself in the middle of the situation to protect her and her senator husband from scandal. His loyalty to her causes him to become the center of the police investigation and the prime suspect. As the plot develops, Carter has to resort to his own investigation, with the help of his gay lover, to discover the root of the conspiracy.

When his best friend Lynn Lockner (Kristin Scott Thomas) discovers her lover murdered, it is Carter who puts himself in the middle of the situation to protect her and her senator husband from scandal. His loyalty to her causes him to become the center of the police investigation and the prime suspect. As the plot develops, Carter has to resort to his own investigation, with the help of his gay lover, to discover the root of the conspiracy. The Walker uses Carter's homosexuality as a device to enable him to become friends with the wealthy women without causing their husbands concern. Yet, the film's images of the gay lifestyle are at times troubling. His lover's job as a gay artist, creating agitprop posters of nude men being tortured are disturbing and unnecessary.

The Walker uses Carter's homosexuality as a device to enable him to become friends with the wealthy women without causing their husbands concern. Yet, the film's images of the gay lifestyle are at times troubling. His lover's job as a gay artist, creating agitprop posters of nude men being tortured are disturbing and unnecessary.

Cut to 5 years later and we find Penny's father kidnapped and Bolt and Penny involved in trying to rescue him. The ensuing chase scene is like something from the opening of a James Bond film. Exciting, nail-biting, Bolt is seen to be a super-dog with super-powers. He can run faster than a speeding bullet. He has heat-ray vision. He can stop a moving truck. And his bark is something to behold. It can literally raise the roof. There's even a shot using "bullet-time" made famous in

Cut to 5 years later and we find Penny's father kidnapped and Bolt and Penny involved in trying to rescue him. The ensuing chase scene is like something from the opening of a James Bond film. Exciting, nail-biting, Bolt is seen to be a super-dog with super-powers. He can run faster than a speeding bullet. He has heat-ray vision. He can stop a moving truck. And his bark is something to behold. It can literally raise the roof. There's even a shot using "bullet-time" made famous in  The rest of the film is the story of Bolt's journey from New York across the country back to Hollywood. In New York he is taken to the mangy alley-cat Mittens (Susie Essman), a Don Corleone-like figure who extorts food from the local pigeons in return for protection. She is likely to make them an offer they cannot refuse. But Bolt sees her as one of the evil creatures in league with the green-eyed man, and takes her prisoner, making her help him find Penny.

The rest of the film is the story of Bolt's journey from New York across the country back to Hollywood. In New York he is taken to the mangy alley-cat Mittens (Susie Essman), a Don Corleone-like figure who extorts food from the local pigeons in return for protection. She is likely to make them an offer they cannot refuse. But Bolt sees her as one of the evil creatures in league with the green-eyed man, and takes her prisoner, making her help him find Penny. En route they meet Rhino (Mark Walton), an overweight hamster who inexplicably lives in a plastic ball. Rhino is a TV-obsessed mammal who idolizes Bolt and wants to accompany his hero, even if it means "eating danger for breakfast."

En route they meet Rhino (Mark Walton), an overweight hamster who inexplicably lives in a plastic ball. Rhino is a TV-obsessed mammal who idolizes Bolt and wants to accompany his hero, even if it means "eating danger for breakfast." As much fun as Bolt is, it also raises several issues deeply embedded in its narrative, each appropriate to one of the three animals on the journey. The first relates to heroes. Bolt is the star of his TV show and believes he is a super-dog. He expects to save Penny, his owner. But like Buzz Lightyear in the earlier Pixar film Toy Story he learns that he is no superhero. He is an ordinary dog. But in real-life there are no super-heroes, just ordinary people who can become heroes. Just as Bolt becomes a real hero, we can be to those we interact with. Even if it does not involve rescue from imminent danger, if we help those in need we can be heroes. We are here to serve and love those in our communities. Whether that involves mentoring a young boy in an inner-city school, coaching a girls' soccer team, or serving at a rescue mission, there are needy and hurting people desperately seeking a champion. You or I can be that hero.

As much fun as Bolt is, it also raises several issues deeply embedded in its narrative, each appropriate to one of the three animals on the journey. The first relates to heroes. Bolt is the star of his TV show and believes he is a super-dog. He expects to save Penny, his owner. But like Buzz Lightyear in the earlier Pixar film Toy Story he learns that he is no superhero. He is an ordinary dog. But in real-life there are no super-heroes, just ordinary people who can become heroes. Just as Bolt becomes a real hero, we can be to those we interact with. Even if it does not involve rescue from imminent danger, if we help those in need we can be heroes. We are here to serve and love those in our communities. Whether that involves mentoring a young boy in an inner-city school, coaching a girls' soccer team, or serving at a rescue mission, there are needy and hurting people desperately seeking a champion. You or I can be that hero. Mittens, on the other hand, is no hero. She carries within her a secret, one she dares not share. It is her "power." She has been wounded before. We have all been wounded by others. How we deal with these wounds determines who we become. If we allow the wounds to fester we will become bitter, cynical, liars, who in turn hurt and wound others. We might feel it our "right" since others had done likewise to us. We can stop this cycle through forgiving, letting go of the past, and bringing truth to our relationships (Col. 3:13).

Mittens, on the other hand, is no hero. She carries within her a secret, one she dares not share. It is her "power." She has been wounded before. We have all been wounded by others. How we deal with these wounds determines who we become. If we allow the wounds to fester we will become bitter, cynical, liars, who in turn hurt and wound others. We might feel it our "right" since others had done likewise to us. We can stop this cycle through forgiving, letting go of the past, and bringing truth to our relationships (Col. 3:13). Rhino was a straight-up hero-worshiper. A fan, he wanted to follow his idol regardless of the danger it might put him in. He is an unlikely example of what a Jesus-follower looks like. For us, Jesus is our hero. He is the one we want to follow at whatever cost. If it means picking up our cross and facing death (Matt. 10:38); if it means walking into the valley of the shadow of death (Psa. 23:4); if it means staring into the face of Satan and not backing down (1 Pet. 5:8-9), we will do it if Jesus takes us there. Will we be like Rhino in our worship of the true hero, Jesus?

Rhino was a straight-up hero-worshiper. A fan, he wanted to follow his idol regardless of the danger it might put him in. He is an unlikely example of what a Jesus-follower looks like. For us, Jesus is our hero. He is the one we want to follow at whatever cost. If it means picking up our cross and facing death (Matt. 10:38); if it means walking into the valley of the shadow of death (Psa. 23:4); if it means staring into the face of Satan and not backing down (1 Pet. 5:8-9), we will do it if Jesus takes us there. Will we be like Rhino in our worship of the true hero, Jesus?

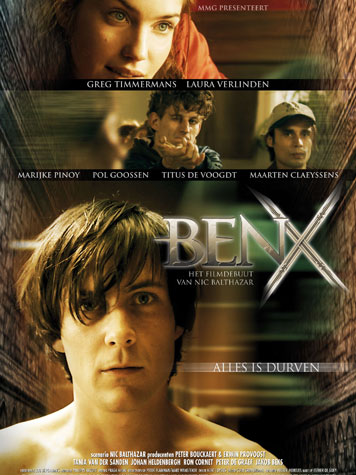

Ben is a young man with Asperger's Syndrome, a brain disorder and form of autism. This condition has in part led to the his parents' divorce. Because autism carries with it both behavioral and emotional difficulties, Ben stands out as "different" at school. And in a large public school, different is not what you want to be. It is clear he is not "normal." And several bullies pick on him ruthlessly while the rest of the class participates in this ongoing humiliation of Ben.

Ben is a young man with Asperger's Syndrome, a brain disorder and form of autism. This condition has in part led to the his parents' divorce. Because autism carries with it both behavioral and emotional difficulties, Ben stands out as "different" at school. And in a large public school, different is not what you want to be. It is clear he is not "normal." And several bullies pick on him ruthlessly while the rest of the class participates in this ongoing humiliation of Ben. As the plot develops, we see some of the bullying that Ben experienced in his younger years. Clearly, he has had it rough. But it is at the hands of two"normal" bullies Desmet (Maarten Claeyssens) and Bogaert (Titus De Voogdt) that he is pushed over the edge. The bullying intensifies until it reaches a particularly mean incident in front of the whole classroom, and then beyond. Humiliated and angry, Ben still won't communicate to the teachers or principal.

As the plot develops, we see some of the bullying that Ben experienced in his younger years. Clearly, he has had it rough. But it is at the hands of two"normal" bullies Desmet (Maarten Claeyssens) and Bogaert (Titus De Voogdt) that he is pushed over the edge. The bullying intensifies until it reaches a particularly mean incident in front of the whole classroom, and then beyond. Humiliated and angry, Ben still won't communicate to the teachers or principal. An intriguing part of the story is that Ben, inept and awkward in real life, is a macho hero in an on-line role-playing game that he plays daily. In this virtual reality that he escapes to he can recreate himself to be whoever he wants. And in doing so, he has attained a level of power and superiority, and has found a girlfriend/princess. Indeed, the beginning of the movie plays like the start of a video game, with clever credits coming up as entry points into Ben's other world. What he cannot feel in reality he can feel in cyberspace.

An intriguing part of the story is that Ben, inept and awkward in real life, is a macho hero in an on-line role-playing game that he plays daily. In this virtual reality that he escapes to he can recreate himself to be whoever he wants. And in doing so, he has attained a level of power and superiority, and has found a girlfriend/princess. Indeed, the beginning of the movie plays like the start of a video game, with clever credits coming up as entry points into Ben's other world. What he cannot feel in reality he can feel in cyberspace.

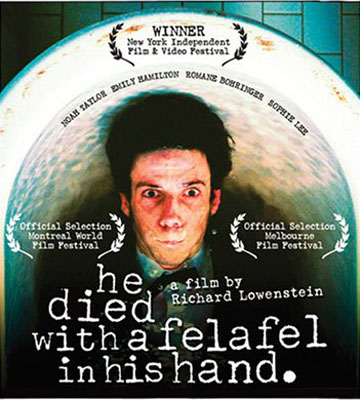

The story-line revolves around "room-mates from hell" in eastern Australia. These room-mates include: foul-mouth "bruces" doing drugs and seeking sex; a chaos-inducing Russian lesbian who creates trouble for all; a homosexual coming out to no surprise; a self-absorbed soap actress; and a Japanese student who is given a broom-closet for a room.

The story-line revolves around "room-mates from hell" in eastern Australia. These room-mates include: foul-mouth "bruces" doing drugs and seeking sex; a chaos-inducing Russian lesbian who creates trouble for all; a homosexual coming out to no surprise; a self-absorbed soap actress; and a Japanese student who is given a broom-closet for a room.

At first Kit just wants to enjoy her friends, her tree-house and her dream to be reporter. But slowly the depression affects her. She sees friends lose their homes. She sees kids at school bully and humiliate those impacted. But until it hits home, she is still insulated. When she sees her dad, a car salesman (Chris O'Donnell), at a soup kitchen, her world is rocked. As he leaves for Chicago and the hopes of a job, her mom Margaret is forced to take in boarders to make ends meet. Kit sacrifices her room to a paying lodger.

At first Kit just wants to enjoy her friends, her tree-house and her dream to be reporter. But slowly the depression affects her. She sees friends lose their homes. She sees kids at school bully and humiliate those impacted. But until it hits home, she is still insulated. When she sees her dad, a car salesman (Chris O'Donnell), at a soup kitchen, her world is rocked. As he leaves for Chicago and the hopes of a job, her mom Margaret is forced to take in boarders to make ends meet. Kit sacrifices her room to a paying lodger. The lodgers that come to Kit's home are a strange bunch. There's the mom with son (Kit's friend), whose husband has also left the state looking for work. She is humbled but still considers herself better than the hobos who live in shanty towns and travel the country jumping trains. Alongside her is the dance instructor who is desperately looking for a husband, any husband, and any man with a pulse will do. Throw in a magician and a mobile librarian who can barely drive and you have a houseful of odd ducks.

The lodgers that come to Kit's home are a strange bunch. There's the mom with son (Kit's friend), whose husband has also left the state looking for work. She is humbled but still considers herself better than the hobos who live in shanty towns and travel the country jumping trains. Alongside her is the dance instructor who is desperately looking for a husband, any husband, and any man with a pulse will do. Throw in a magician and a mobile librarian who can barely drive and you have a houseful of odd ducks.

As the film progresses, so do the characters. Bruno begins to see that Schmuel and the others in pajamas are different, or at least are treated differently. He is confused. He likes his friend, Schmuel, but learns that he is a Jew, and Jews are supposed to be evil, animals, the cause of all that is wrong with Germany. Meanwhile, father (David Thewliss, Lupin in the Harry Potter movies), is simply doing his duty serving his country, unquestioningly killing the Jews in the gas chamber, while mother (Vera Farmiga, from The Departed) knows nothing. Life goes on for her until she finally discovers what the foul-smelling smoke from the camp really is. Then she is devastated and starts to come unglued.

As the film progresses, so do the characters. Bruno begins to see that Schmuel and the others in pajamas are different, or at least are treated differently. He is confused. He likes his friend, Schmuel, but learns that he is a Jew, and Jews are supposed to be evil, animals, the cause of all that is wrong with Germany. Meanwhile, father (David Thewliss, Lupin in the Harry Potter movies), is simply doing his duty serving his country, unquestioningly killing the Jews in the gas chamber, while mother (Vera Farmiga, from The Departed) knows nothing. Life goes on for her until she finally discovers what the foul-smelling smoke from the camp really is. Then she is devastated and starts to come unglued. The casting director for The Boy in the Striped Pajamas really scored. Asa Butterfield, in only his second feature film (his first was a minor role in Son of Rambow) is astonishing. His large blue eyes, seen in close-ups of his face so often, convey an innocence and naivety. With the restrained direction of director and screenwriter Mark Herman, Butterfield looks like a veteran. The other boy, Scanlon, cast after Butterfield was in place, has excellent chemistry as the powerless and hungry friend. This is his first feature and certainly won't be his last. The two adults hold their own, too. Thewliss eschews cliche in his role, playing the commandant not as a total monster but as a person who loves his family while slowly sliding down the slippery slope of sin and evil. He based this performance on the autobiography of Rudolph Höß, commandant of Auschwitz, written during the Nuremburg trials. But Farmiga, as mother, shows perhaps how some Germans must have felt, truly conflicted about the awfulness of Hitler's "final solution."

The casting director for The Boy in the Striped Pajamas really scored. Asa Butterfield, in only his second feature film (his first was a minor role in Son of Rambow) is astonishing. His large blue eyes, seen in close-ups of his face so often, convey an innocence and naivety. With the restrained direction of director and screenwriter Mark Herman, Butterfield looks like a veteran. The other boy, Scanlon, cast after Butterfield was in place, has excellent chemistry as the powerless and hungry friend. This is his first feature and certainly won't be his last. The two adults hold their own, too. Thewliss eschews cliche in his role, playing the commandant not as a total monster but as a person who loves his family while slowly sliding down the slippery slope of sin and evil. He based this performance on the autobiography of Rudolph Höß, commandant of Auschwitz, written during the Nuremburg trials. But Farmiga, as mother, shows perhaps how some Germans must have felt, truly conflicted about the awfulness of Hitler's "final solution."

th mature themes. Set around 1915, the era of silent movies, stuntman Roy (Lee Pace) lies paralyzed and depressed in a Los Angeles hospital. His body is broken from a crazy leap from a bridge while filming an impossible stunt. His heart is broken by the actress girlfriend who left him for the leading man. His hope is gone.

th mature themes. Set around 1915, the era of silent movies, stuntman Roy (Lee Pace) lies paralyzed and depressed in a Los Angeles hospital. His body is broken from a crazy leap from a bridge while filming an impossible stunt. His heart is broken by the actress girlfriend who left him for the leading man. His hope is gone. The story Roy tells is an epic tale of revenge. Five men from different lands and backgrounds are exiled to a remote tropical island by the evil Governor Odious. When they escape by riding on swimming elephants, it is clear that realism is subverted and imagination is highlighted. They embark on a quest to avenge their losses.

The story Roy tells is an epic tale of revenge. Five men from different lands and backgrounds are exiled to a remote tropical island by the evil Governor Odious. When they escape by riding on swimming elephants, it is clear that realism is subverted and imagination is highlighted. They embark on a quest to avenge their losses. Toward the end, the 5 heroes in the tale start dying even as Roy is dying. This is tough for young Alexandria, and crying she asks, "Why are you making everyone die?" This does not make sense for a 5 year-old. Stories for kids just don't do this.

Toward the end, the 5 heroes in the tale start dying even as Roy is dying. This is tough for young Alexandria, and crying she asks, "Why are you making everyone die?" This does not make sense for a 5 year-old. Stories for kids just don't do this.

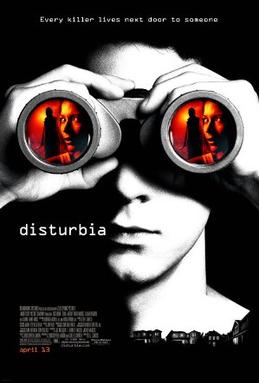

When Kale starts to suspect Mr Turner is more than he seems, the film kicks into gear. Soon, Ashley joins Kale and goofy buddy Ronnie (Aaron Yoo) in their spying sessions. Morse gives Turner a s sinister feel, but only enough that he could just be an honest neighbor. When he finds out they are intruding on his privacy, spying on him, Disturbia becomes creepy and suspenseful.

When Kale starts to suspect Mr Turner is more than he seems, the film kicks into gear. Soon, Ashley joins Kale and goofy buddy Ronnie (Aaron Yoo) in their spying sessions. Morse gives Turner a s sinister feel, but only enough that he could just be an honest neighbor. When he finds out they are intruding on his privacy, spying on him, Disturbia becomes creepy and suspenseful. Disturbia also raises the issue of privacy and spying on neigbors. Jesus tells us to love our neighbors as ourselves, the second great commandmant (Matt. 22:39). Is it loving to spy on them, to pry into their lives? Even though this might lead to the occasional discovery of the Mr. Turner's out there, who can answer this with a yes? No, to love our neighbors is to serve them and allow them to retain the level of privacy they desire.

Disturbia also raises the issue of privacy and spying on neigbors. Jesus tells us to love our neighbors as ourselves, the second great commandmant (Matt. 22:39). Is it loving to spy on them, to pry into their lives? Even though this might lead to the occasional discovery of the Mr. Turner's out there, who can answer this with a yes? No, to love our neighbors is to serve them and allow them to retain the level of privacy they desire.

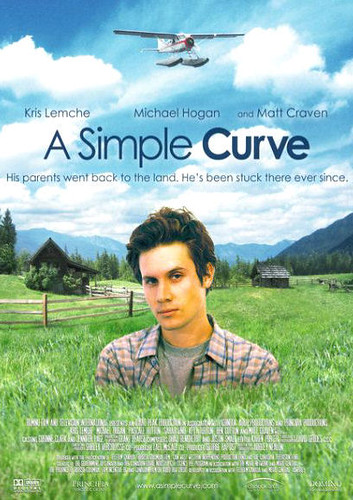

Caleb cannot persuade Jim to do what the customers want at the price they want. Jim wants to discover what is in the wood waiting to be made, regardless of the project. Not really a great way to run a business. And all that is running is their profits -- straight into the red.

Caleb cannot persuade Jim to do what the customers want at the price they want. Jim wants to discover what is in the wood waiting to be made, regardless of the project. Not really a great way to run a business. And all that is running is their profits -- straight into the red. The title is taken from the simple curve at the top of the chair that Matthew asks for as a demo of Jim's work. Initially Jim creates a magnificent work of art, using a compound curve. It is a chair befitting a king, but it is expensive and cannot sustain the cash flow needed in their business or by Matthew in his lodge.

The title is taken from the simple curve at the top of the chair that Matthew asks for as a demo of Jim's work. Initially Jim creates a magnificent work of art, using a compound curve. It is a chair befitting a king, but it is expensive and cannot sustain the cash flow needed in their business or by Matthew in his lodge. When Lee asks him, later, if he really wants to spend his life in the valley it forces Caleb to face the question of his future. Where he had simply accepted that he would be with his dad in the shop, eking out a living, he now has a new thought in his head. Then when Matthew gives him a piece of advice, that all boys need to tell their dad to get lost (not the exact phrase used, but toned down for this blog), another piece of the puzzle enters his brain. He has never stood up to his dad and pulled away.

When Lee asks him, later, if he really wants to spend his life in the valley it forces Caleb to face the question of his future. Where he had simply accepted that he would be with his dad in the shop, eking out a living, he now has a new thought in his head. Then when Matthew gives him a piece of advice, that all boys need to tell their dad to get lost (not the exact phrase used, but toned down for this blog), another piece of the puzzle enters his brain. He has never stood up to his dad and pulled away. Towards the climax, an earlier secret long-buried is shared by Jim with Caleb, a secret that is shocking. This is a secret that is enough to push Caleb over the edge.

Towards the climax, an earlier secret long-buried is shared by Jim with Caleb, a secret that is shocking. This is a secret that is enough to push Caleb over the edge.