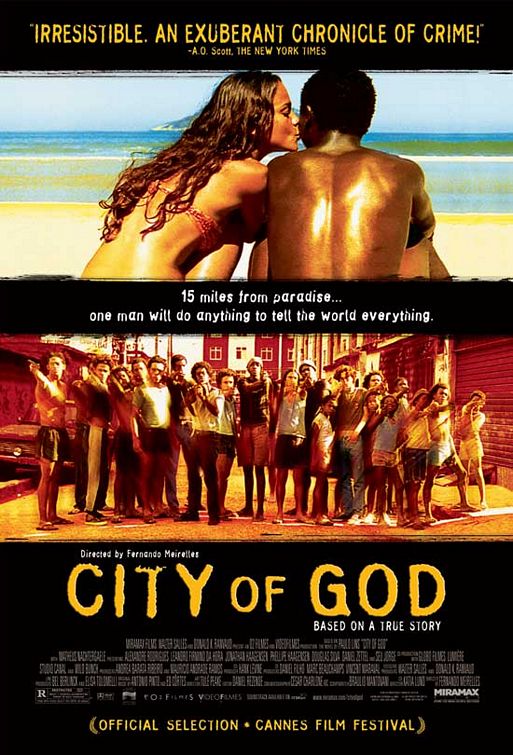

Directors: Fernando Meirelles & Kátia Lund, 2002.

There are places where angels fear to tread, and the police avoid. City of God is just such a place. It is a slum. A suburb of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 25 miles from paradise, the poorest of the poor live there in squalor and a war-like environment.

City of God is a brutally violent film that depicts the drugs, the guns, and the ferocity of the gangs. Not for the faint of heart, this is based on a true story and is filled with amateur actors recruited from the slums. Indeed, the actor who plays Rocket (Alexandre Rodrigues), the main narrator, actually lived in Cicade de Deus itself. And those in the cast not from this slum lived there for three months to prepare for the film. Yet, it could not be shot there since it was too dangerous. Rather, it had to be filmed in a less violent neighborhood of Rio.

The film opens with a festive atmosphere, bright colors and loud samba music. The camera focuses on a chicken, its foot tied to prevent its escape. As other chickens are killed and prepared for cooking, this one senses danger and imminent death. When it frees itself and runs off into the narrow streets, it is pursued by a gang of kids and young adults led by Li'l Zé (Leandro Firmino). When Rocket and his friend approach the chicken down an alley, the gang, armed to the teeth stand at one end while the police show up at the other. Rocket faces his personal dilemma: "If you run you're dead . . . if you stay, you're dead." What to do? The fun has turned to fear and the film is underway.

The film opens with a festive atmosphere, bright colors and loud samba music. The camera focuses on a chicken, its foot tied to prevent its escape. As other chickens are killed and prepared for cooking, this one senses danger and imminent death. When it frees itself and runs off into the narrow streets, it is pursued by a gang of kids and young adults led by Li'l Zé (Leandro Firmino). When Rocket and his friend approach the chicken down an alley, the gang, armed to the teeth stand at one end while the police show up at the other. Rocket faces his personal dilemma: "If you run you're dead . . . if you stay, you're dead." What to do? The fun has turned to fear and the film is underway.The film moves two decades back to the 60s, where Rocket is a young boy, the son of a fishmonger. As Rocket narrates the story, he continually stops to tell the backstory of characters whose lives intersect with the current events.

It starts with the Tender Trio, three teen hoods who commit petty crime, robbing propane gas trucks. But when a younger brother, Li'l Dice (Douglas Silva) who later changes his name to Li'l Zé, comes up with the idea of robbing a motel/brothel, their life of crime becomes more serious. Li'l Dice is given a gun to act as lookout. But guns and kids don't mix. Kids don't have a sense of mortality and the magnitude of taking a life is missing. When Li'l Dice kills the people in the motel petty crime has become major felony.

It starts with the Tender Trio, three teen hoods who commit petty crime, robbing propane gas trucks. But when a younger brother, Li'l Dice (Douglas Silva) who later changes his name to Li'l Zé, comes up with the idea of robbing a motel/brothel, their life of crime becomes more serious. Li'l Dice is given a gun to act as lookout. But guns and kids don't mix. Kids don't have a sense of mortality and the magnitude of taking a life is missing. When Li'l Dice kills the people in the motel petty crime has become major felony. From simple stealing to murder, Li'l Dice enjoys the power of violence. Graduating from robbery to the easier money in drugs, he moves into dealing and control. Only his childhood friend Benny (Phellipe Haagensen) can calm his murderous impulses. Cutting to the 70s Li'l Zé runs a gang and takes over the areas of the slum by mercilessly wiping out rival gangs and gangleaders.

From simple stealing to murder, Li'l Dice enjoys the power of violence. Graduating from robbery to the easier money in drugs, he moves into dealing and control. Only his childhood friend Benny (Phellipe Haagensen) can calm his murderous impulses. Cutting to the 70s Li'l Zé runs a gang and takes over the areas of the slum by mercilessly wiping out rival gangs and gangleaders.Meirelles employs a variety of filmic techniques including time-jumping and freeze-framing in this contemporary rendition of a gang-warfare story. Where Scorsese gave us the violent Gangs of New York, with professional Oscar-winning actors like Daniel Day Lewis, Meirelles' amateurs are more violent, more chilling and more lifelike. The adult gang members of those New York gangs would have not survived in the City of God. The life expectancy of the Brazilian gangs seems to be much less, perhaps 20 years.

Toward the end, a scene stands out for its jarring juxtaposition of apparent faith and its anti-faith walk. As one of the gangs is preparing its firepower ready to go kill another gang, the kids stop and together recite the Lord's Prayer. This was not scripted, but one of the actors, formerly an actual gang member, said they always prayed before going to battle. But as we think of this prayer that Jesus taught his disciples (Matt. 6:9-13), we are reminded that in the very same sermon on the mount just moments before, Jesus also said these words: "Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you" (Matt. 5:43). Faith in Jesus should lead to prayer and love. Praying and then killing is anathema to a true life of faith.

At its heart, City of God portrays the sense of hopelessness of these kids in the poverty-stricken slums. Their future was to join the police or join the gangs. The police were corrupt, but were afraid to come into the City of God. The gangs, on the other hand, offered the prospect of easy money, a sense of belonging, and a life of power. With the overwhelming prevalence of drugs, with pot and coke given to kids at a young age, it is easy to see how addiction would lead naturally to membership or soldierhood. And lack of hope manifests in lack of mercy.

Another South American film deals with poverty and hopelessness. The Pope's Toilet, a Uruguayan movie, shows a village on the Brazilian border with corrupt police and a poor populace. Yet, there the only crime was that of petty smuggling across the border. No one resorted to drug dealing and violence. Poverty does not have to lead to gangs and murder.

Indeed, set against the hopelessness of most of the characters in City of God Rocket's story is that of redemption. Rejecting the life of crime, he has an artist's eye and a passion for photography. He sees this as his ticket to freedom. Given a camera, he finds himself able to show the world the battle that is going on between the two final rival gangs in his city.

Indeed, set against the hopelessness of most of the characters in City of God Rocket's story is that of redemption. Rejecting the life of crime, he has an artist's eye and a passion for photography. He sees this as his ticket to freedom. Given a camera, he finds himself able to show the world the battle that is going on between the two final rival gangs in his city.Even with its brutality, City of God reminds us that everyone needs hope. Without hope we die. Without hope of a future, we gravitate to anything that can satisfy immediately. For these street kids, it was guns and drugs. For Americans, it might be alcohol and drugs, or sex and porn. But there is a hope. There is an offer of redemption. It is not in photography, like Rocket's redemption. It is in Jesus. He offers us the hope of life, real life, even in the midst of tough circumstances, if we turn to him in faith. Just as Rocket put his faith in his camera, we can put our faith in Christ.

Copyright ©2009, Martin Baggs

No comments:

Post a Comment