Director: Pedro Almodóvar, 2002.

Midway through Talk to Her a ballet teacher says to one of the main characters, "Nothing is simple." This is true of life and it is true of this movie. A beautifully layered drama that combines elements of tragedy, comedy and romance, Talk to Her has plenty of material to make people think. Some viewers will no doubt be shocked by some of the content, especially the surreal silent movie within the movie. But others will find Almodóvar's film challenging and provocative at the same time as being artful and imaginative. The Academy found it creative enough to award him the 2003 Best Original Screenplay Oscar.

The movie opens in a small theater where Marco (Dario Grandinetti) is watching an emotional dance performance. Moved to tears, his sensitivity is noticed by Benigni (Javier Camara), the stranger sitting next to him. Later their paths will cross and a friendship will emerge that will make Marco, at least, a better man.

Marco, a journalist, begins a relationship with Lydia (Rosario Flores), a female bullfighter. But it takes a tragic turn when she is savagely gored by a bull in the ring. Comatose, she is taken to a private hospital where she lays still, a vegetative victim to violence. Marco can only wait by her side.

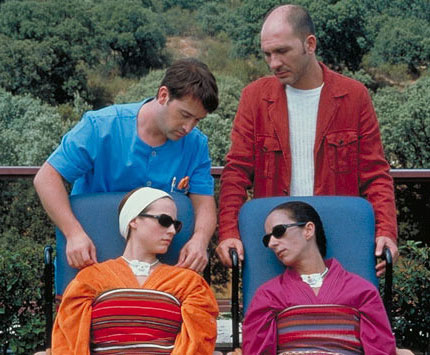

It is in this hospital that Marco runs into Benigni, a male nurse and caregiver to Alicia (Leonor Watling), a ballet student who has been in a coma for four years. Benigni is a quiet-spoken man, almost effeminate, possibly homosexual. Remembering seeing Marco cry at the dance show, Benigni initiates their friendship. He shows Marco how he is lovingly caring for Alicia, massaging her, stroking her, reading to her, and talking to her as if she were conscious.

Craig Detweiler, in his book "Into the Dark," focuses a chapter on this movie and provides an insightful analysis. He says, "Almodóvar challenges us to look closer, to judge characters not by their orientations (or our assumptions) but by their actions." Indeed since the director is gay we might expect Benigni's friendship with Marco to move toward the sexual, but Almodóvar defies stereotypes. Where caregivers are normally female, they are male here. Where men are usually bullfighters, Lydia is the show-woman here. And where the female is most often the one who does more talking in a relationship, here it is the men who must talk. The two sylphs simply lay like silent specters, still yet impacting the men.

Interestingly, in one scene Marco is talking with Lydia in a car on the way to a bull fight but he is not really talking to her. He is more talking to himself in her presence. She comments that they need to talk after the fight. It is only after she descends into a coma that Marco really begins to talk to her.

Detweiler adds, "Hablo con ella" is about two men learning to communicate." As such it makes us consider our own modes of communication. Talk to Her challenges men to reflect on our conversations with our friends and our partners. Are we really talking to them? Are we listening to what our wife or partner may be saying? Or are we speaking but not listening, more interested in a monologue? Are we prepared to have a true two-way discourse? Marco needed the shock of seeing his woman comatose to do this.

As the movie unfolds, it uses flashbacks to reveal layers of the principle characters. Benigni in particular is not what he appears. He seems to be benign and caring but he is delusional. The object of his love, the comatose Alicia, barely knows him. This love is unrequited. Benigni has manufactured a romance in his head and comes to believe in this fabrication. How much of our inner conversation, what we say to ourselves, is real? Do we ever delude ourselves into a affirming a reality that is a figment of our own imagination? To some degree, we do. We put our slant on what happens to us. We bring a subjective perspective to our life. That is all too evident in witness testimony in court where those who see the same event report it differently. Although some of that is simply subconscious, there is also the "spin" we put on things at work and at home so we appear better than we should. The more we spin, the more we believe our own press releases. This is dangerous, for us and others.

As the movie unfolds, it uses flashbacks to reveal layers of the principle characters. Benigni in particular is not what he appears. He seems to be benign and caring but he is delusional. The object of his love, the comatose Alicia, barely knows him. This love is unrequited. Benigni has manufactured a romance in his head and comes to believe in this fabrication. How much of our inner conversation, what we say to ourselves, is real? Do we ever delude ourselves into a affirming a reality that is a figment of our own imagination? To some degree, we do. We put our slant on what happens to us. We bring a subjective perspective to our life. That is all too evident in witness testimony in court where those who see the same event report it differently. Although some of that is simply subconscious, there is also the "spin" we put on things at work and at home so we appear better than we should. The more we spin, the more we believe our own press releases. This is dangerous, for us and others.In Talk to Her, Benigni's delusions becomes dangerous for Alicia, though she is no position to do anything about it. As Benigni has started to do things in his spare time that she would have liked, he sees a surreal silent movie, "The Shrinking Lover." This movie within a movie includes a bizarre sexual encounter, but is used by Almodóvar as a plot device to communicate what is going on in Benigni's real life.

The state of the two comatose women highlights the ethical dilemma medicine finds itself in today. The 2004 film Million Dollar Baby put boxer Maggie (Hilary Swank) in a quadriplegic position wishing to take her own life but unable to do so. Hence she pleaded with her trainer Frankie (Clint Eastwood) to do the unthinkable. Assisted suicide was the ethical conundrum. But Talk to Her puts the victim in a state where no conversation can occur. In a coma, the person lays as though dead. The question, then, becomes is she alive? What is life? And should it be maintained mechanically via medical technology, even if there appears to be no brain activity and no possibility of such? Is life more than the physical body?

The state of the two comatose women highlights the ethical dilemma medicine finds itself in today. The 2004 film Million Dollar Baby put boxer Maggie (Hilary Swank) in a quadriplegic position wishing to take her own life but unable to do so. Hence she pleaded with her trainer Frankie (Clint Eastwood) to do the unthinkable. Assisted suicide was the ethical conundrum. But Talk to Her puts the victim in a state where no conversation can occur. In a coma, the person lays as though dead. The question, then, becomes is she alive? What is life? And should it be maintained mechanically via medical technology, even if there appears to be no brain activity and no possibility of such? Is life more than the physical body?Life is complex. Biblically, life is more than merely physical. There is an immaterial aspect, soul or spirit (1 Thess. 5:23). But if the brain is dead, is the soul or spirit present? Or is it waiting for release with physical death to go be in its future state, whether heaven or hell? Do we have the right to "pull the plug" on such a comatose person? The arguments have raged both before and after Terri Schiavo's feeding tube was removed. Certainly, pulling back such mechanistic modes of keeping a person alive may prevent a possible future miraculous intervention by the divine Healer.

The ballet teacher raises another key point when she is visiting Alicia in the hospital and talking to Benigni. She says she is going to Geneva to conduct a ballet about war, where male dancers are soldiers who die and ballerinas emerge, as their souls. Life is emerging from death. Benigi's actions later bring life but a cost to himself and others. Jesus said that a seed has to die before life can come forth (Jn. 12:24). He was speaking of the death to self that we must undergo if we want to live the true life offered in him. Life emerges from death (Rom. 8:13).

In the end Almodóvar leaves us questioning how we feel towards Benigni. Marco has grown in his sensitivity and his communication. But Benigni has brought good out of evil. Is this right? When such good comes from an abhorrent act how should we treat the victim? And how should we treat the culprit? What if the culprit is delusional, does that make any difference? These are questions that are left hanging for us to ponder. Will our faith emerge stronger for such a pondering, that is for each of us to consider.

Copyright ©2009, Martin Baggs

No comments:

Post a Comment