Director: Joel Coen, 1991.

The Coen brothers are probably the most versatile film-makers working today. They write their own scripts; they direct the films; and they usually edit their own work under pseudonyms. They have made film noir (Blood Simple, The Man Who Wasn't There), comedy (Raising Arizona, The Big Lebowski), bleak crime (No Country for Old Men), even romantic comedy (Intolerable Cruelty). Barton Fink, their fourth film, defies simple genre identification. It starts as a drama with touches of comedy and ends as a surreal film noir. But it resists a simple narrative resolution and so is ambiguous and frustrating.

The Coens have won the biggest prize, the Best Film Oscar, for No Country. But Barton Fink achieved the distinction of winning the top three awards at the Cannes Film Festival: Best Actor (John Turturro), Best Director, and Palm D'Or (best picture). Indeed, after this, the Cannes organizers decreed that future films could win only two awards at most.

Barton Fink opens in 1941 at the backstage of a Broadway play where playwright Barton Fink (Turturro) is watching the debut of his new play. It is a huge success, being appreciated by both the general audience and the critics. When he is offered serious money to move to Hollywood to become a script-writer for Capital Pictures he at first refuses. But with the influence of his agent, the money beckons and Barton goes.

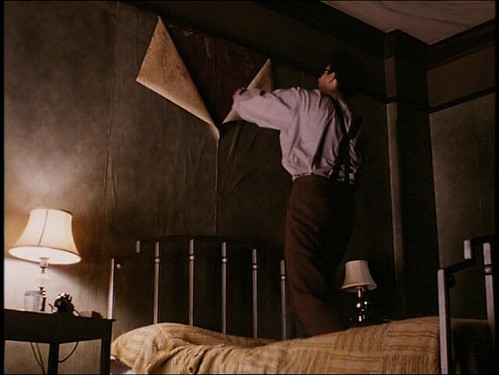

Barton Fink opens in 1941 at the backstage of a Broadway play where playwright Barton Fink (Turturro) is watching the debut of his new play. It is a huge success, being appreciated by both the general audience and the critics. When he is offered serious money to move to Hollywood to become a script-writer for Capital Pictures he at first refuses. But with the influence of his agent, the money beckons and Barton goes.In Los Angeles Fink moves into the weird, seemingly abandoned Hotel Earle. Stylized in art-deco fashion, it seems to be full of residents and transients, yet Fink sees none except his sixth-floor neighbor, Charlie Meadows (John Goodman) a door-to-door insurance salesman. Hotel Earle is slowly decaying and has seen better days. Fink's room is bare of any decor except a cheap picture of a bikini-clad woman on the beach gazing into the surf. The picture is a key theme in the film, as Fink repeatedly stares at it, and the camera returns to it time and time again.

Barton Fink is filled with themes and symbols. The Coen brothers offer some clear contrasts particularly in the area of entertainment. Fink hails from New York, home of the theater and Broadway. This is high-culture. Works of art, these plays are labors of love that playwrights like Fink have struggled to produce. In contrast, Los Angeles is the home of Hollywood and low culture. Film-makers mechanically turn out formulaic B-movies to spin profits, not to make art. The audience they cater to is the plebeian, the philistine, not the connoisseur.

Watching Barton Fink causes us to reflect on own preferences in entertainment. Do we prefer movies to stage-plays? Do we choose formulaic films, action, thrillers, rather than movies that might make us meditate? Are we looking for some form of escape from the daily grind or an encounter with the divine God?

Another inherent theme is the ideal of the common man. Fink is a leftist intellectual, and sees himself as the champion of these underprivileged people. Yet, ironically he is not one of them; instead he is self-obsessed and sees himself as a suffering creator. And he cannot see the common man when he is right in front of him. Charlie, his neighbor, is that archetype. Fat, sweaty, overly cheery and friendly, ready to share a drink and a joke, he is Common Man. But when Charlie says to Fink, "I could tell you some stories," Fink cuts him off and spouts off on his own soap-box. He will not listen.

Another inherent theme is the ideal of the common man. Fink is a leftist intellectual, and sees himself as the champion of these underprivileged people. Yet, ironically he is not one of them; instead he is self-obsessed and sees himself as a suffering creator. And he cannot see the common man when he is right in front of him. Charlie, his neighbor, is that archetype. Fat, sweaty, overly cheery and friendly, ready to share a drink and a joke, he is Common Man. But when Charlie says to Fink, "I could tell you some stories," Fink cuts him off and spouts off on his own soap-box. He will not listen.Isolation, loneliness and frustration are additional themes. Fink spends most of his time in his room looking at his typewriter. He is struggling with writer's block having been ordered to write a wrestling movie script. Apparently surrounded by other hotel-dwellers, he is alone in one of the biggest cities in America. When he seeks the friendship of another writer, the famous W.P. Mayhew (John Mahoney), he discovers Mayhew is a drunk and something of a fraud, living with a lover Audrey (Judy Davis). Even these are not really his friends. He has no one to turn to. His agent is in New York. The movie producer is no help. And the mogul expects results not excuses.

When he turns to Audrey for help, late one night before a meeting with the film studio mogul, Fink is beside himself with worry. Her assistance is to reduce his tension. But when he awakes to a nightmare situation, the film itself becomes taut with tension and turns from a light drama to a darker film noir, with unexpected twists and turns.

Surrealism shows up in the eerie hotel. With an early reference to 666, the number of the beast in Revelation (Rev. 13:18), there is more to the hotel than meets the eye. Hotel Earle seems more like Hotel Hell. With New York symbolizing heaven (to Fink) LA symbolizes hell. Indeed, the hotel is hot as hell and the wallpaper in Fink's room starts to peel, dripping gooey paste like Charlie's pus-dripping ear infection. Yet, strangely this only seems to occur when Charlie is near. Is Charlie who he seems to be, a friendly pal? Or is he something more sinister? Is he perhaps the devil incarnate?

Surrealism shows up in the eerie hotel. With an early reference to 666, the number of the beast in Revelation (Rev. 13:18), there is more to the hotel than meets the eye. Hotel Earle seems more like Hotel Hell. With New York symbolizing heaven (to Fink) LA symbolizes hell. Indeed, the hotel is hot as hell and the wallpaper in Fink's room starts to peel, dripping gooey paste like Charlie's pus-dripping ear infection. Yet, strangely this only seems to occur when Charlie is near. Is Charlie who he seems to be, a friendly pal? Or is he something more sinister? Is he perhaps the devil incarnate?Certainly the character of Charlie Meadows reminds us that Satan is the master masquerader. He comes across looking like an angel of light (2 Cor. 11:14) yet is a demon of darkness. We do not expect to see the devil. He is portrayed as a little red demon with horns, a tail and a pitchfork. Yet he is more likely to come to us as a Charlie Meadows, the buddy next door, who wins our friendship and tempts us to turn from truth to sin. Only by standing firm in the strength of the Lord Jesus (Eph. 6:10-18) can we ordinary Jesus-followers expect to gain victory in the spiritual battle that we find ourselves in.

The most prominent theme in Barton Fink is the process of writing. Fink struggles with writer's block for most of the film. He says to Charlie at one point, "I've always found that writing comes from great inner pain." But his inner pain and suffering cannot produce a script about wrestling. Even Charlie's help, as a former wrestler, is to no avail. Only when Charlie gives him a brown-paper wrapped box for storage, does his mind start working. The box becomes a sort of muse for Fink. Perhaps it is the suffering that comes in the second half of the film combined with this muse that finally enables Fink to turn out a screenplay in one long sitting. Even then, it is the story of a wrestler's soul-suffering, more intellectual than the B-movie script he is being paid for. It is a creation not a formulaic copy. In celebration he cries maniacally to a dancing throng, "I'm a writer, you monsters! I create! I create for a living! I'm a creator! I am a creator!"

The most prominent theme in Barton Fink is the process of writing. Fink struggles with writer's block for most of the film. He says to Charlie at one point, "I've always found that writing comes from great inner pain." But his inner pain and suffering cannot produce a script about wrestling. Even Charlie's help, as a former wrestler, is to no avail. Only when Charlie gives him a brown-paper wrapped box for storage, does his mind start working. The box becomes a sort of muse for Fink. Perhaps it is the suffering that comes in the second half of the film combined with this muse that finally enables Fink to turn out a screenplay in one long sitting. Even then, it is the story of a wrestler's soul-suffering, more intellectual than the B-movie script he is being paid for. It is a creation not a formulaic copy. In celebration he cries maniacally to a dancing throng, "I'm a writer, you monsters! I create! I create for a living! I'm a creator! I am a creator!"In this statement Fink identifies one aspect of the image of God in humanity. God, the Creator, decided to create man and woman in his image as the very apex of his overall creation (Gen. 1:26). We are uniquely endowed with a soul and spirit. And we are given the ability to create. This can take many forms, such as the creation of art, of literature, of writings. These are to be enjoyed as reflections of the one primary Creator.

Toward the end, in another surrealistic scene, Fink sits on the beach and sees a beautiful woman in a bikini approach him. She sits next to him and gazes out at the surf in the identical pose to the woman in the picture in his room. Fink has moved into the picture and she has stepped into reality. This underscores the tension between the objective and the subjective points of view in art. The line between imagination and reality has blurred. The creator has become one with the creation. How real is art? How real are films?

Toward the end, in another surrealistic scene, Fink sits on the beach and sees a beautiful woman in a bikini approach him. She sits next to him and gazes out at the surf in the identical pose to the woman in the picture in his room. Fink has moved into the picture and she has stepped into reality. This underscores the tension between the objective and the subjective points of view in art. The line between imagination and reality has blurred. The creator has become one with the creation. How real is art? How real are films?This scene evokes the descent from heaven into our reality of the Creator. Jesus, the one who made and now sustains all that we see (Col. 1:16-17), left his position of glory to enter into his creation. He joined the story. He walked into the picture. He became one of us (Phil. 2:8). He took on human flesh, skin and bone. He did that so that he might offer himself in our place on the cross that was destined for each one of us. As Barton Fink entered into this pictorial creation, so Jesus Christ entered into his physical creation. But though Barton Fink ends with an ambiguity that refuses to explain many of the symbols, Jesus stands ready with clear-cut options: life with him, heaven; death apart from him, hell.

Copyright ©2009, Martin Baggs

No comments:

Post a Comment