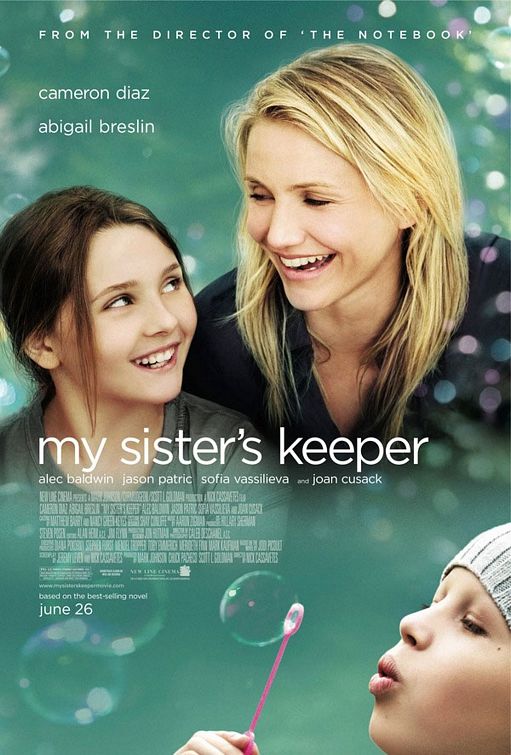

Director: Nick Cassavetes, 2009

The first murderer, when confronted with the question, "Where is your brother?" lied, "I don't know." Then added, in a gesture of angry denial, "Am I my brother's keeper?" This story, of course, comes from the opening chapters of the Bible (Gen. 4:8-9), and highlights the bonds of sibling care and dependence that were expected from Cain (the murderer) and his brother Abel. Similar sibling bonds form the foundation of the story, based on the book by Jodi Picoult, from writer-director Cassavetes (The Notebook).

From the very start, even as the opening credits are playing, we hear 11-year-old Anna Fitzgerald (Abigail Breslin, Little Miss Sunshine, Definitely Maybe) describe the conception and birth of babies. Though most are "accidents" she is not. She is most unusual. She is a genetically engineered girl, a made-to-order baby.

Anna's older sister Kate (Sofia Vassilieva) is dying with a rare form of leukemia. We see her with her family after the credits enjoying an idyllic summer day in LA, blowing bubbles in the air. These bubbles epitomize the buoyancy yet fragililty of life. So easily floating away into the blue sky they pop and disappear so quickly. Kate's life is like that. Her joie de vivre will be over almost before has it begun.

Through a series of flashbacks we see the "development" of this family. At an early age mom Sara (Cameron Diaz) and dad (Jason Patric) are told that young Kate has the disease. Their doctor tells them, off-the-record, that a genetically engineering child would be a perfect match for blood and bone marrow transplants. Of course, ethically he is not allowed to make such a recommendation or even suggestion. But Sara snags this ray of hope in her suddenly dark world and along comes Anna. Made as a spare parts child, Anna is her sister's keeper in the real physical sense.

Through a series of flashbacks we see the "development" of this family. At an early age mom Sara (Cameron Diaz) and dad (Jason Patric) are told that young Kate has the disease. Their doctor tells them, off-the-record, that a genetically engineering child would be a perfect match for blood and bone marrow transplants. Of course, ethically he is not allowed to make such a recommendation or even suggestion. But Sara snags this ray of hope in her suddenly dark world and along comes Anna. Made as a spare parts child, Anna is her sister's keeper in the real physical sense.This moral dilemma is center stage in My Sister's Keeper, yet surprisingly the ethics are not really explored. Rather than focus on the issue of whether a baby should be conceived in vitro for the sole sake of being available to provide for another person, the film focuses on the emotional and physical after-effects in the lives of Anna and her family.

Yet, this is certainly an important issue. President Bush signed the "Fetus Farming Prohibition Act" of 2006 to prevent intentional creation and use of human fetal tissues or organs for scientific or medical purposes. But fetuses carried to term become babies whose rights are governed by their parents. So, is it morally acceptable to birth a genetically crafted child for the purpose of helping an older sibling? In a 1991 real-life parallel to Anna and Kate, the Ayala family from LA conceived a girl to help their older daughter Anissa who was suffering from leukemia. But their daughter Marissa was not genetically manipulated and they trusted God to give them a child that would be a genetic match to Anissa. Their motive was apparently to steward the life that had already been given them, with an additional emphasis on the new life added to their family. Their motivation was seemingly positive and scriptural.

So, an answer to this complex question must involve motivation on the part of the parents and how they balance the needs and health care of their donor-child.

In My Sister's Keeper, Sara is completely obsessed with caring for and healing Kate. This is to the extreme, and all else is subservient to this single-minded goal. Clearly, she is not balanced in her approach to her family and other children.

So it is a surprise to Sara when she is delivered a subpoena to appear in court. She is being sued by her own daughter Anna, who wants medical emancipation from her parents so she does not have to struggle and suffer the pain and possible long-term effects of further operations in support of her sister. Anna has contracted the support of showboat lawyer Campbell Alexander (Alec Baldwin).

So it is a surprise to Sara when she is delivered a subpoena to appear in court. She is being sued by her own daughter Anna, who wants medical emancipation from her parents so she does not have to struggle and suffer the pain and possible long-term effects of further operations in support of her sister. Anna has contracted the support of showboat lawyer Campbell Alexander (Alec Baldwin).As the film moves toward a climax, there is a moving scene in the judge's chambers where Judge De Salvo (Joan Cusack) wants to assess Anna's ability to understand what she is asking for. There is an emotional connection between the two based on loss. Indeed, the courtroom scene, where first Sara then Anna are put on the stand, is powerful and stands up to other courtroom scenes, such as To Kill a Mockingbird.

My Sister's Keeper is not perfect, by any means. It veers into sentimentality at points and gross-out imagery at others. Its nonlinear narrative enables it to gloss over a number of plot holes quickly and quietly. It underplays the male characters to overplay the three female leads. And it traverses a fairly predictable and emotionally depressing path only to add a snippet of Hollywood hope at the end.

My Sister's Keeper is not perfect, by any means. It veers into sentimentality at points and gross-out imagery at others. Its nonlinear narrative enables it to gloss over a number of plot holes quickly and quietly. It underplays the male characters to overplay the three female leads. And it traverses a fairly predictable and emotionally depressing path only to add a snippet of Hollywood hope at the end.Yet, for all this, it was an engaging and thought-provoking movie. It raises additional issues of age of responsibility for control over your body as well as the point of letting go. At what point are we able to make informed decisions about our own bodies instead of being under the governance of our parents? The film sets up the scene well but never really delivers a solid answer.

As for the time when life veers into death, when is the time to die with grace? Is it more important, as Sara seems to think, to strive for every additional minute or month, regardless of the cost in dollars or lives impacted? There comes a time for all of us when life will run out, when our last breath is but a moment away. The wise king Solomon once wrote a poem about this in the third chapter of Ecclesiastes.

1 There is a time for everything, and a season for every activity underThere is a time for everything and we need to be ready to die as we have lived: with grace. In this way, even in death can we glorify our God who has given us the gift of life and the time on this earth to prepare for our eternal life in heaven (or hell) that will follow.

heaven:

2 a time to be born and a time to die,

a time to plant and a time to uproot,

3 a time to kill and a time to heal,

a time to tear down and a time to build,

4 a time to weep and a time to laugh,

a time to mourn and a time to dance,

5 a time to scatter stones and a time

to gather them, a time to embrace and a time to refrain,

6 a time to search and a time to give up,

a time to keep and a time to throw away,

7 a time to tear and a time to mend,

a time to be silent and a time to speak,

8 a time to love and a time to hate,

a time for war and a time for peace.

Copyright ©2009, Martin Baggs

No comments:

Post a Comment