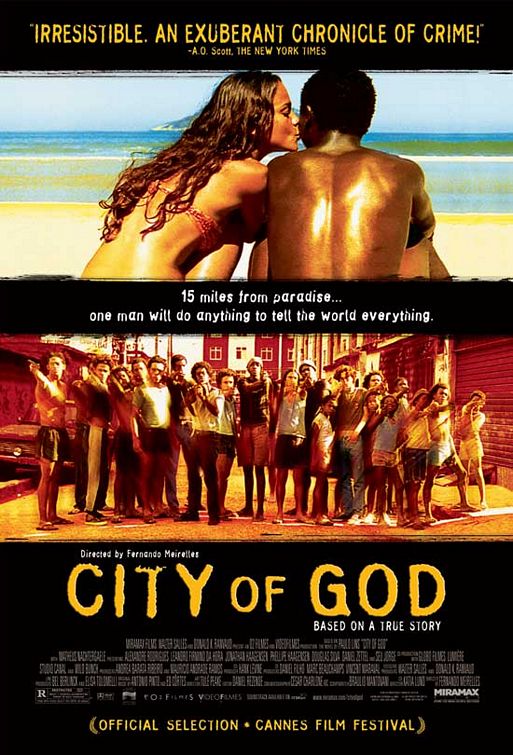

Directors: Fernando Meirelles & Kátia Lund, 2002.

There are places where angels fear to tread, and the police avoid. City of God is just such a place. It is a slum. A suburb of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 25 miles from paradise, the poorest of the poor live there in squalor and a war-like environment.

City of God is a brutally violent film that depicts the drugs, the guns, and the ferocity of the gangs. Not for the faint of heart, this is based on a true story and is filled with amateur actors recruited from the slums. Indeed, the actor who plays Rocket (Alexandre Rodrigues), the main narrator, actually lived in Cicade de Deus itself. And those in the cast not from this slum lived there for three months to prepare for the film. Yet, it could not be shot there since it was too dangerous. Rather, it had to be filmed in a less violent neighborhood of Rio.

The film opens with a festive atmosphere, bright colors and loud samba music. The camera focuses on a chicken, its foot tied to prevent its escape. As other chickens are killed and prepared for cooking, this one senses danger and imminent death. When it frees itself and runs off into the narrow streets, it is pursued by a gang of kids and young adults led by Li'l Zé (Leandro Firmino). When Rocket and his friend approach the chicken down an alley, the gang, armed to the teeth stand at one end while the police show up at the other. Rocket faces his personal dilemma: "If you run you're dead . . . if you stay, you're dead." What to do? The fun has turned to fear and the film is underway.

The film opens with a festive atmosphere, bright colors and loud samba music. The camera focuses on a chicken, its foot tied to prevent its escape. As other chickens are killed and prepared for cooking, this one senses danger and imminent death. When it frees itself and runs off into the narrow streets, it is pursued by a gang of kids and young adults led by Li'l Zé (Leandro Firmino). When Rocket and his friend approach the chicken down an alley, the gang, armed to the teeth stand at one end while the police show up at the other. Rocket faces his personal dilemma: "If you run you're dead . . . if you stay, you're dead." What to do? The fun has turned to fear and the film is underway.The film moves two decades back to the 60s, where Rocket is a young boy, the son of a fishmonger. As Rocket narrates the story, he continually stops to tell the backstory of characters whose lives intersect with the current events.

It starts with the Tender Trio, three teen hoods who commit petty crime, robbing propane gas trucks. But when a younger brother, Li'l Dice (Douglas Silva) who later changes his name to Li'l Zé, comes up with the idea of robbing a motel/brothel, their life of crime becomes more serious. Li'l Dice is given a gun to act as lookout. But guns and kids don't mix. Kids don't have a sense of mortality and the magnitude of taking a life is missing. When Li'l Dice kills the people in the motel petty crime has become major felony.

It starts with the Tender Trio, three teen hoods who commit petty crime, robbing propane gas trucks. But when a younger brother, Li'l Dice (Douglas Silva) who later changes his name to Li'l Zé, comes up with the idea of robbing a motel/brothel, their life of crime becomes more serious. Li'l Dice is given a gun to act as lookout. But guns and kids don't mix. Kids don't have a sense of mortality and the magnitude of taking a life is missing. When Li'l Dice kills the people in the motel petty crime has become major felony. From simple stealing to murder, Li'l Dice enjoys the power of violence. Graduating from robbery to the easier money in drugs, he moves into dealing and control. Only his childhood friend Benny (Phellipe Haagensen) can calm his murderous impulses. Cutting to the 70s Li'l Zé runs a gang and takes over the areas of the slum by mercilessly wiping out rival gangs and gangleaders.

From simple stealing to murder, Li'l Dice enjoys the power of violence. Graduating from robbery to the easier money in drugs, he moves into dealing and control. Only his childhood friend Benny (Phellipe Haagensen) can calm his murderous impulses. Cutting to the 70s Li'l Zé runs a gang and takes over the areas of the slum by mercilessly wiping out rival gangs and gangleaders.Meirelles employs a variety of filmic techniques including time-jumping and freeze-framing in this contemporary rendition of a gang-warfare story. Where Scorsese gave us the violent Gangs of New York, with professional Oscar-winning actors like Daniel Day Lewis, Meirelles' amateurs are more violent, more chilling and more lifelike. The adult gang members of those New York gangs would have not survived in the City of God. The life expectancy of the Brazilian gangs seems to be much less, perhaps 20 years.

Toward the end, a scene stands out for its jarring juxtaposition of apparent faith and its anti-faith walk. As one of the gangs is preparing its firepower ready to go kill another gang, the kids stop and together recite the Lord's Prayer. This was not scripted, but one of the actors, formerly an actual gang member, said they always prayed before going to battle. But as we think of this prayer that Jesus taught his disciples (Matt. 6:9-13), we are reminded that in the very same sermon on the mount just moments before, Jesus also said these words: "Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you" (Matt. 5:43). Faith in Jesus should lead to prayer and love. Praying and then killing is anathema to a true life of faith.

At its heart, City of God portrays the sense of hopelessness of these kids in the poverty-stricken slums. Their future was to join the police or join the gangs. The police were corrupt, but were afraid to come into the City of God. The gangs, on the other hand, offered the prospect of easy money, a sense of belonging, and a life of power. With the overwhelming prevalence of drugs, with pot and coke given to kids at a young age, it is easy to see how addiction would lead naturally to membership or soldierhood. And lack of hope manifests in lack of mercy.

Another South American film deals with poverty and hopelessness. The Pope's Toilet, a Uruguayan movie, shows a village on the Brazilian border with corrupt police and a poor populace. Yet, there the only crime was that of petty smuggling across the border. No one resorted to drug dealing and violence. Poverty does not have to lead to gangs and murder.

Indeed, set against the hopelessness of most of the characters in City of God Rocket's story is that of redemption. Rejecting the life of crime, he has an artist's eye and a passion for photography. He sees this as his ticket to freedom. Given a camera, he finds himself able to show the world the battle that is going on between the two final rival gangs in his city.

Indeed, set against the hopelessness of most of the characters in City of God Rocket's story is that of redemption. Rejecting the life of crime, he has an artist's eye and a passion for photography. He sees this as his ticket to freedom. Given a camera, he finds himself able to show the world the battle that is going on between the two final rival gangs in his city.Even with its brutality, City of God reminds us that everyone needs hope. Without hope we die. Without hope of a future, we gravitate to anything that can satisfy immediately. For these street kids, it was guns and drugs. For Americans, it might be alcohol and drugs, or sex and porn. But there is a hope. There is an offer of redemption. It is not in photography, like Rocket's redemption. It is in Jesus. He offers us the hope of life, real life, even in the midst of tough circumstances, if we turn to him in faith. Just as Rocket put his faith in his camera, we can put our faith in Christ.

Copyright ©2009, Martin Baggs

Angelo does escape and survives by taking to the roof, becoming the titular horseman on the roof. When he drops into an attic, it is the temporary residence of Pauline. Living alone, her aunts having fled the disease earlier, he acts honorably to her. With no one to protect her, Angelo could have had his way with the gorgeous woman but he had been taught how to treat a lady. The chivalry and respect he shows her is surprising and refreshing. Pleasing, indeed, to see honor in a hero.

Angelo does escape and survives by taking to the roof, becoming the titular horseman on the roof. When he drops into an attic, it is the temporary residence of Pauline. Living alone, her aunts having fled the disease earlier, he acts honorably to her. With no one to protect her, Angelo could have had his way with the gorgeous woman but he had been taught how to treat a lady. The chivalry and respect he shows her is surprising and refreshing. Pleasing, indeed, to see honor in a hero.

The four other monsters are derived from the horror films of the fifties and early sixties. Susan is a reference to Attack of the 50 Foot Woman. Dr Cockroach (Hugh Laurie) is a mad scientist turned into a cockroach in one of his experiments, a scenario taken from The Fly. The evolutionary Missing Link (Will Arnett) is like the Creature from the Black Lagoon. Insectosaurus is modelled off Mosura (aka Mothra in the US). And B.O.B is a take on The Blob. Of all these creatures, B.O.B was my favorite. He seemed likable, despite his lack of brain. Created from a genetically engineered tomato, he is more like Bob the Tomato of Veggie Tales than the killer tomatoes from Attack of the Killer Tomatoes!

The four other monsters are derived from the horror films of the fifties and early sixties. Susan is a reference to Attack of the 50 Foot Woman. Dr Cockroach (Hugh Laurie) is a mad scientist turned into a cockroach in one of his experiments, a scenario taken from The Fly. The evolutionary Missing Link (Will Arnett) is like the Creature from the Black Lagoon. Insectosaurus is modelled off Mosura (aka Mothra in the US). And B.O.B is a take on The Blob. Of all these creatures, B.O.B was my favorite. He seemed likable, despite his lack of brain. Created from a genetically engineered tomato, he is more like Bob the Tomato of Veggie Tales than the killer tomatoes from Attack of the Killer Tomatoes! The second scene comes when the President realizes the military cannot handle this robot. At Gen. Monger's suggestion, he sends in the monsters to take care of things. Their journey through a deserted San Francisco (shades of

The second scene comes when the President realizes the military cannot handle this robot. At Gen. Monger's suggestion, he sends in the monsters to take care of things. Their journey through a deserted San Francisco (shades of

This is one of the strengths of the movie. It portrays real life. These could be your next-door neighbors; they are not the pretty actors we see in American movies, but bald and fat people. By avoiding any musical soundtrack, Puiu does not play our emotions like a violin, as in most Hollywood films. We are left to feel what we would feel naturally.

This is one of the strengths of the movie. It portrays real life. These could be your next-door neighbors; they are not the pretty actors we see in American movies, but bald and fat people. By avoiding any musical soundtrack, Puiu does not play our emotions like a violin, as in most Hollywood films. We are left to feel what we would feel naturally. As the ambulance takes Lazarescu to hospital after hospital, Marioara is his sole advocate. Time and time again the predominantly young doctors dismiss her concerns regarding Lazarescu's colon. Instead they treat her with scorn. She is merely a paramedic, not a doctor. Their arrogance drips from their tongues. It makes us reflect on our own approach to people who are "less educated" than ourselves. We may have one or more degrees but that does not mean we have a monopoly on wisdom or truth. When we stop listening to others who may know more than us, who can teach us something, we are dangerously close to educational suicide. There is no place for arrogance in the Christian life. Our finitude means we can never know everything. There will always be something that someone can teach us.

As the ambulance takes Lazarescu to hospital after hospital, Marioara is his sole advocate. Time and time again the predominantly young doctors dismiss her concerns regarding Lazarescu's colon. Instead they treat her with scorn. She is merely a paramedic, not a doctor. Their arrogance drips from their tongues. It makes us reflect on our own approach to people who are "less educated" than ourselves. We may have one or more degrees but that does not mean we have a monopoly on wisdom or truth. When we stop listening to others who may know more than us, who can teach us something, we are dangerously close to educational suicide. There is no place for arrogance in the Christian life. Our finitude means we can never know everything. There will always be something that someone can teach us. The Death of Mr Lazarescu is a little overlong and the last twenty minutes seem to drag. But the ending is non-judgmental and leaves the viewer hanging. There is no clear closure. But perhaps that is the point. There are no easy answers when it comes to the issues of health care. The system is not perfect, not even close. But it is the one the Romanians have. And it is on display here.

The Death of Mr Lazarescu is a little overlong and the last twenty minutes seem to drag. But the ending is non-judgmental and leaves the viewer hanging. There is no clear closure. But perhaps that is the point. There are no easy answers when it comes to the issues of health care. The system is not perfect, not even close. But it is the one the Romanians have. And it is on display here.

As a young child Salvatore, nicknamed Toto, was an altarboy alongside Father Adelfio (Leopoldo Trieste). After mass, Father Adelfio would go to the Cinema Paradiso to pre-screen the upcoming film while Toto would sneak into the projectionist booth to be with Alfredo (Philippe Noiret) the projectionist. Whenever the priest would see a kissing scene he would ring the bell and Alfredo would mark the spot for cutting.

As a young child Salvatore, nicknamed Toto, was an altarboy alongside Father Adelfio (Leopoldo Trieste). After mass, Father Adelfio would go to the Cinema Paradiso to pre-screen the upcoming film while Toto would sneak into the projectionist booth to be with Alfredo (Philippe Noiret) the projectionist. Whenever the priest would see a kissing scene he would ring the bell and Alfredo would mark the spot for cutting. Salvatore Cascio is perfect as the young Toto, a cute yet mischievous child with large adorable eyes. He has great chemistry with Noiret. Marco Leonardi carries the role through the teenage years, when Toto falls in love for the first time with Elena (Agnese Nano), but her university studies and his national service bring their ill-fated romance to an end. Yet, this is a romance that the adult Salvatore (Jacques Perrin) has not moved beyond. In the new version of the film, where almost an hour of unseen footage is added, she reenters the movie to be reacquainted with the adult Toto, but the original version never brings her back into the picture. For Toto, his two loves were film-making and Elena. He could not have both.

Salvatore Cascio is perfect as the young Toto, a cute yet mischievous child with large adorable eyes. He has great chemistry with Noiret. Marco Leonardi carries the role through the teenage years, when Toto falls in love for the first time with Elena (Agnese Nano), but her university studies and his national service bring their ill-fated romance to an end. Yet, this is a romance that the adult Salvatore (Jacques Perrin) has not moved beyond. In the new version of the film, where almost an hour of unseen footage is added, she reenters the movie to be reacquainted with the adult Toto, but the original version never brings her back into the picture. For Toto, his two loves were film-making and Elena. He could not have both. Moreover, the second issue emerges from the first. What is the relationship between the church and the cinema? Father Adolfio made himself the village censor, forcing Alfredo to cut and snip any scene that he considered morally inappropriate for his flock of parishioners. But is this the role of the church? Can we not, as Christian adults, make decisions for ourselves?

Moreover, the second issue emerges from the first. What is the relationship between the church and the cinema? Father Adolfio made himself the village censor, forcing Alfredo to cut and snip any scene that he considered morally inappropriate for his flock of parishioners. But is this the role of the church? Can we not, as Christian adults, make decisions for ourselves?

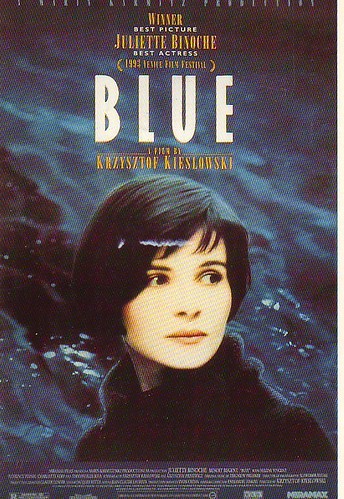

Julie hangs her blue mobile in her new apartment. Jeffrey Overstreet, in his book "Through a Screen Darkly," comments extensively on Blue. He says these stones "are like strands of suspended crystalline tears, pieces of sharp-edged grief that Julie has not been able to express." For me, they seem to be a metaphor for her past and its memories. In her farmhouse, she tore some and let them fall, cascading, onto the wooden floor. Yet she was not willing to let them all go, despite her apparent intention. She repressed her memories but still carried them with her into Paris. When her neighbor, an exotic dancer, approaches this mobile, the fear and sense of violation is clear on Julie's face. These are her memories, they cannot be shared.

Julie hangs her blue mobile in her new apartment. Jeffrey Overstreet, in his book "Through a Screen Darkly," comments extensively on Blue. He says these stones "are like strands of suspended crystalline tears, pieces of sharp-edged grief that Julie has not been able to express." For me, they seem to be a metaphor for her past and its memories. In her farmhouse, she tore some and let them fall, cascading, onto the wooden floor. Yet she was not willing to let them all go, despite her apparent intention. She repressed her memories but still carried them with her into Paris. When her neighbor, an exotic dancer, approaches this mobile, the fear and sense of violation is clear on Julie's face. These are her memories, they cannot be shared. When her neighbor calls her to the exotic dance club late one night, Julie sees herself on the TV. She realizes that her husband's final unfinished composition for the unification of Europe, which she thought she had destroyed, is being finished by her friend Olivier (Benoît Régent). She had abandoned this symphony but it would not abandon her. Indeed, a busker had told her, "You have to hold onto something," and finally she realizes it is the music which will liberate her. The symphony will come out; it must be finished.

When her neighbor calls her to the exotic dance club late one night, Julie sees herself on the TV. She realizes that her husband's final unfinished composition for the unification of Europe, which she thought she had destroyed, is being finished by her friend Olivier (Benoît Régent). She had abandoned this symphony but it would not abandon her. Indeed, a busker had told her, "You have to hold onto something," and finally she realizes it is the music which will liberate her. The symphony will come out; it must be finished. In contrast, when she understands that she must face her loss and move on, the music of the symphony under-construction becomes her healing balm. Again, Kieslowski uses creative camerawork and technique to let us experience the music being written as Julie would experience it, and there is a beautiful mystery about this. There is grace in this healing, and this grace works its way into and through Julie in how she comes to deal graciously with those around her, even those who have hurt her. Grace is even present in the finale, with a choir singing 1 Corinthians 13 in Greek as the orchestral composition hits its climax.

In contrast, when she understands that she must face her loss and move on, the music of the symphony under-construction becomes her healing balm. Again, Kieslowski uses creative camerawork and technique to let us experience the music being written as Julie would experience it, and there is a beautiful mystery about this. There is grace in this healing, and this grace works its way into and through Julie in how she comes to deal graciously with those around her, even those who have hurt her. Grace is even present in the finale, with a choir singing 1 Corinthians 13 in Greek as the orchestral composition hits its climax.

The slow pacing of the directors allows us to see and experience the hopelessness of these lives. The beauty of the natural scenery juxtaposes with the ugliness of the people's homes. Poverty is an obstacle that seems insurmountable. It reminds us of Jesus' saying, "The poor you will always have with you" (Matt. 26:11). In saying this, Jesus is not endorsing poverty or social injustice. He is merely making it clear that in this life in this world, there will not be a solution to this societal problem. Only when his kingdom is firmly established, in the Millennium and beyond, will poverty be eliminated.

The slow pacing of the directors allows us to see and experience the hopelessness of these lives. The beauty of the natural scenery juxtaposes with the ugliness of the people's homes. Poverty is an obstacle that seems insurmountable. It reminds us of Jesus' saying, "The poor you will always have with you" (Matt. 26:11). In saying this, Jesus is not endorsing poverty or social injustice. He is merely making it clear that in this life in this world, there will not be a solution to this societal problem. Only when his kingdom is firmly established, in the Millennium and beyond, will poverty be eliminated.

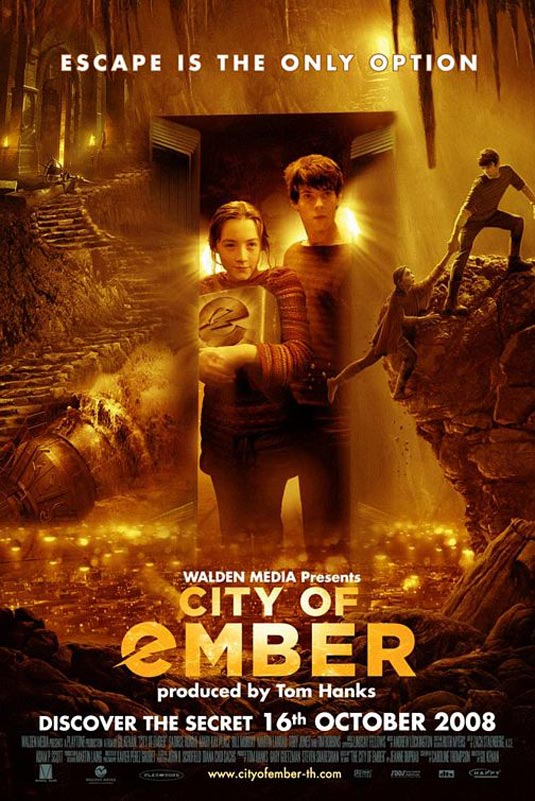

When Lina discovers the metal box and the message it contains, it seems to be a clear sign. With no one else focusing on the imminent dangers of the dying generator, Doon and Lina take destiny into their own hands and look for a way out of Ember.

When Lina discovers the metal box and the message it contains, it seems to be a clear sign. With no one else focusing on the imminent dangers of the dying generator, Doon and Lina take destiny into their own hands and look for a way out of Ember. Early in the film, the Mayor declares that Ember is the city of light in a world of darkness. Jesus said something similar to describe Christians. As Jesus is the light of the world (Jn. 9:5), so his followers are lights to the world, reflecting Jesus to those in darkness (Matt. 6:14-16). We in the church comprise a city of light in this dark world. As we allow Jesus to shine forth through us those around us can see the truth.

Early in the film, the Mayor declares that Ember is the city of light in a world of darkness. Jesus said something similar to describe Christians. As Jesus is the light of the world (Jn. 9:5), so his followers are lights to the world, reflecting Jesus to those in darkness (Matt. 6:14-16). We in the church comprise a city of light in this dark world. As we allow Jesus to shine forth through us those around us can see the truth. The Mayor himself can be compared to some biblical leaders. In a position of power and authority, Mayor Cole has put his own needs and desires above his people. He is no longer serving them, he is looking out for number one. The power accorded his office has corrupted him so that he seeks self-preservation. Even the the two kids on their mission to save Ember are perceived as a threat. The Pharisees were like that when Jesus came the first time. He preached a gospel message that was good news to the poor and marginalized (Lk. 4:18-19) but bad news to those in authority, since this authority was threatened. Jesus' light shone too brightly for these leaders and to retain their power they had to commit the worst sin in history: the murder of Messiah. They were not serving the Jews, they were serving themselves.

The Mayor himself can be compared to some biblical leaders. In a position of power and authority, Mayor Cole has put his own needs and desires above his people. He is no longer serving them, he is looking out for number one. The power accorded his office has corrupted him so that he seeks self-preservation. Even the the two kids on their mission to save Ember are perceived as a threat. The Pharisees were like that when Jesus came the first time. He preached a gospel message that was good news to the poor and marginalized (Lk. 4:18-19) but bad news to those in authority, since this authority was threatened. Jesus' light shone too brightly for these leaders and to retain their power they had to commit the worst sin in history: the murder of Messiah. They were not serving the Jews, they were serving themselves.

Ignoring her orders, he waits and is arrested. He finds himself in a cell being interrogated by Agent Thomas Morgan (Billy Bob Thornton). He is in deep trouble. But when he is given his one call, the outgoing call is intercepted by this mysterious woman who tells him to get down so she can maneuver his escape. He has no choice but to obey.

Ignoring her orders, he waits and is arrested. He finds himself in a cell being interrogated by Agent Thomas Morgan (Billy Bob Thornton). He is in deep trouble. But when he is given his one call, the outgoing call is intercepted by this mysterious woman who tells him to get down so she can maneuver his escape. He has no choice but to obey. The initial car chase is thrilling, with Holloman being instructed precisely how to drive by the female caller. This strange woman can control the traffic signals and can even remotely take over the cruise control. Escaping death by last minute turns and assists from robotic cranes, it seems there is nowhere that Shaw and Holloman can run or turn to evade whoever is behind their plight. They don't even know what is expected of them. It is a moment by moment journey to who knows where.

The initial car chase is thrilling, with Holloman being instructed precisely how to drive by the female caller. This strange woman can control the traffic signals and can even remotely take over the cruise control. Escaping death by last minute turns and assists from robotic cranes, it seems there is nowhere that Shaw and Holloman can run or turn to evade whoever is behind their plight. They don't even know what is expected of them. It is a moment by moment journey to who knows where. But this movie is not in that league. There is no real chemistry between the two leads, and their characters are paper-thin. The plot is so full of holes that only the presence of the rapid-fire action causes the viewer to suspend disbelief and put all questions on hold. Such as could they really outwit and outfight Morgan? How could they do all that they did without shock kicking in? Why were these two picked seemingly at random? And in the climax in DC, how could Shaw possibly survive? But, hey, this is Hollywood.

But this movie is not in that league. There is no real chemistry between the two leads, and their characters are paper-thin. The plot is so full of holes that only the presence of the rapid-fire action causes the viewer to suspend disbelief and put all questions on hold. Such as could they really outwit and outfight Morgan? How could they do all that they did without shock kicking in? Why were these two picked seemingly at random? And in the climax in DC, how could Shaw possibly survive? But, hey, this is Hollywood.