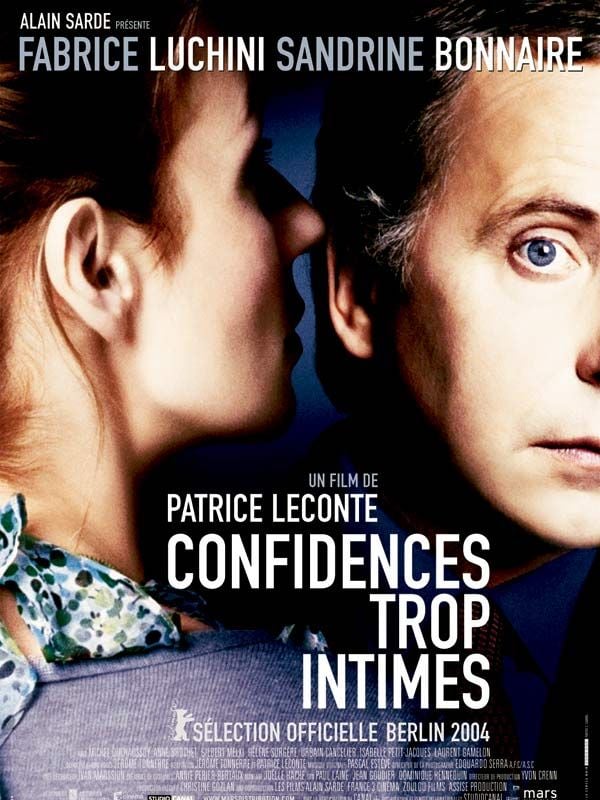

Director: Patrice Leconte, 2004.

Sometimes we need to see a therapist. Imagine sitting down with this counsellor and pouring out your intimate secrets, only later to find out the therapist is actually a tax specialist, a financial advisor! That is the premise of this French drama.

When Anna (Sandrine Bonnaire) exits the elevator in the old Parisian building, she turns left instead of right and knocks on the wrong door. She starts to tell William (Fabrice Luchini) of her marital struggles. As time wraps up, she schedules another appointment with this "doctor," and he has spoken hardly a word. He didn't have the opportunity to correct her misunderstanding.

By the time she finally finds out, she has already divulged sexual secrets and feels emotionally raped. Yet, she has also found a keen listener, one who does not put himself in the middle of the conversation. And she comes back for more of his time and attention.

Leconte gives a slow and gentle meditation on loneliness. As he did in Man on Train he takes us on a journey into the depths of human relationship, exploring two people whose lives are quite lonely. Is this loneliness self-imposed?

Leconte gives a slow and gentle meditation on loneliness. As he did in Man on Train he takes us on a journey into the depths of human relationship, exploring two people whose lives are quite lonely. Is this loneliness self-imposed?William and two other characters in the building offer one perspective on loneliness. The doorkeeper spends her days watching soap operas on TV alone. Even when someone like Anna arrives on the scene, she simply glances at her traverse the corridor to the elevator. William's secretary, a controlling old maid, admits to watching trashy television while eating junk food. A widow, she is happy to pass her time with little human interaction. William voyeuristically watches the couples in the adjacent apartment building, observing their passions and fights. All three have settled for watching life go by outside of them, rather than participating in the actual living of life. Their loneliness is combatted with watching others, not relishing relationships.

However, Anna has an impact on William. She touches something deep inside his soul and causes a flicker of life. And despite acting as "therapist" for Anna, William seeks out the counsel of Dr. Monnier (Michel Duchaussoy), the therapist Anna was originally supposed to visit. He wants to know how to help her. Dr. Monnier offers William some sage advice, "It's the patient's job to lead the hunt for clues. The psychoanalyst knows nothing. He knows the patient knows but the patient doesn't. See?"

However, Anna has an impact on William. She touches something deep inside his soul and causes a flicker of life. And despite acting as "therapist" for Anna, William seeks out the counsel of Dr. Monnier (Michel Duchaussoy), the therapist Anna was originally supposed to visit. He wants to know how to help her. Dr. Monnier offers William some sage advice, "It's the patient's job to lead the hunt for clues. The psychoanalyst knows nothing. He knows the patient knows but the patient doesn't. See?"This is the classic foundation of most counseling: the patient already knows, but needs help in drawing out his or her own answers. It is at the heart of what coaches and mentors do: ask questions and listen to their client or patient. Indeed, William is a good listener, good enough to allow Anna to talk herself through her own problems.

The Bible talks to this, too. James tells us, "My dear brothers, take note of this: Everyone should be quick to listen, slow to speak and slow to become angry" (Jas. 1:19). Some wit once said God gave us two ears but only one tongue so we would listen twice as much as we speak. Regardless of this pithy advice, active listening helps build relationships, and draws the speaker out. The book of Proverbs has many verses telling the reader to listen and grow wise (e.g., Prov. 10:19, 22:17, 23:19). Listening is an art. The person who can do this well, really giving careful attention to another person, empathizes and encourages. This is a skill we need to sharpen.

Listening, though, can be good and bad. William shows both types in his daily work. As he becomes fixated on Anna, his interviews with clients become unimportant to him. Poor listening tunes these people out. They are talking, but William is not really listening. The sound hushes and we cannot even hear them clearly. How often do we listen without really hearing? Our spouse may tell us something while we are surfing the web and we nod and grunt but avoid listening. We are pretending to listen. On the other hand, when Anna is talking William is completely present. He is listening, engrossed in what she has to say. This is the kind of attentive listening we need to give to our spouses. When we do this, we are picking up every word, each subtle nuance, even the unspoken communication of body language.

Listening, though, can be good and bad. William shows both types in his daily work. As he becomes fixated on Anna, his interviews with clients become unimportant to him. Poor listening tunes these people out. They are talking, but William is not really listening. The sound hushes and we cannot even hear them clearly. How often do we listen without really hearing? Our spouse may tell us something while we are surfing the web and we nod and grunt but avoid listening. We are pretending to listen. On the other hand, when Anna is talking William is completely present. He is listening, engrossed in what she has to say. This is the kind of attentive listening we need to give to our spouses. When we do this, we are picking up every word, each subtle nuance, even the unspoken communication of body language.As William's listening draws Anna out, she reveals more and more of herself. She opens up and changes. Leconte makes this evident by her visual changes. Her dour clothing and demeanour are replaced with bright colors and smiles. She comes to a deeper level of self-understanding and self-acceptance.

Who is helping who, though? When Anna tells him that there is a locked door inside him, she has put her finger on his issue. In this way, Leconte forces us to face the question, do we allow ourselves to be intimate with others, or in fear do we choose to remain strangers behind our own locked doors, within our fortresses of solitude? In other words, is our loneliness a form of self-protection?

We can become comfortable in our own loneliness. We can hide behind our habits and behaviors (William's obsessive-compulsive neatness) instead of taking the risk of revealing ourselves. Intimacy connotes the idea of close personal relationship involving love and acceptance. In this sense, "intimate strangers" is a playful oxymoron. We cannot share intimacy with strangers. We can share intimate secrets, but not true intimacy.

To escape our loneliness requires risk-taking. Any time we open our hearts and share secrets or emotions we face the possibility of rejection or humiliation. Sometimes that is too big of a risk. But it is one we must take if we are to share intimacy with a friend or lover. Both Anna and William discovered this, in their own ways, in this film. Will we discover that the power of love will cast out these fears (1 Jn. 4:18)? Will we take the risk of moving beyond being intimate strangers? It might mean choosing the wrong door and then making it the right door!

Copyright ©2010, Martin Baggs

No comments:

Post a Comment