Director: Ben Afleck, 2010. (R)

Afleck's second movie is so similar thematically and stylistically that it could almost be a sequel. Except that his debut film, Gone Baby Gone, had a private investigator as the protagonist while this one has a crook. Further, Afleck himself plays the lead role of Doug MacRay here; in Gone Baby Gone it was his younger brother Casey Afleck in the spotlight and stealing the show. Ben Afleck seems to have a knack for directing strong performances out of his leads and he does that in this film, too, even from himself.

As with his earlier film, The Town is set in working class Boston. This is a gritty, violent movie. It feels real, not a Hollywood version of a crime story. Charlestown, the town in question, is a birth-place for Irish criminals, bank-robbers. Boasting itself as the bank-robbery center of the world, father passes down to son the skills of this illegal trade. MacRay is one of these sons, and his father is doing life for murder after a lifetime of robberies in Charlestown.

This picks up one of the themes from Gone Baby Gone. There, the main character commented at the start that one of the things that define us is the place we are born and grow up. Charlestown seems to underscore this. If you are from Charlestown the odds are seemingly stacked against you. Your future is predefined, your fate is prison. There is no escape.

Is this true? Certainly, birthplace plays a role in defining our potential. But many have risen above their initial circumstances. We need not let our upbringing limit who we are or what we become. Jesus was born in the lowliest of places -- a stable (Lk. 2:7). His parents were poor and living in a small town. Not the choicest locale for the future king of the world! He rose above these limitations. Then he rose from the grave. One day he will come back again in his fully realized position.

MacRay is the brains behind a gang of four thieves who rob banks and armored cars. Alongside him is James Coughlin (Jeremy Renner, The Hurt Locker) as his "blood-brother," a loose cannon friend with a hair-trigger finger. Theirs is a strong love-hate relationship that real brothers understand and "enjoy".

When the initial bank robbery goes down, this team take the assistant bank manager, Claire Keesey (Rebecca Hall), hostage. When they let her go, she feels emotionally torn. She chooses not to reveal all to the lead FBI Agent Frawley (Mad Men's Jon Hamm), holding back a key detail as she feels uncertain and potentially a suspect. Yet, she is suffering mental and emotional trauma from the incident. Finding that she lives just blocks from where they hang out, the robbers realize they must do something to protect themselves. MacRay volunteers and "meets" her at a laundromat. Working his way into her life, he falls in love with the person whose life his violence has disturbed. And he has to balance this secret relationship while plotting his next robbery and evading the FBI.

When the initial bank robbery goes down, this team take the assistant bank manager, Claire Keesey (Rebecca Hall), hostage. When they let her go, she feels emotionally torn. She chooses not to reveal all to the lead FBI Agent Frawley (Mad Men's Jon Hamm), holding back a key detail as she feels uncertain and potentially a suspect. Yet, she is suffering mental and emotional trauma from the incident. Finding that she lives just blocks from where they hang out, the robbers realize they must do something to protect themselves. MacRay volunteers and "meets" her at a laundromat. Working his way into her life, he falls in love with the person whose life his violence has disturbed. And he has to balance this secret relationship while plotting his next robbery and evading the FBI. This is an intriguing setup. The hostage becomes the unknowing lover to the kidnapper. Afleck plays this out through great dialog. The characters are deeper than in most heist movies and Afleck gives them space and time to develop. Even the silences add to this film. The courtship provides an emotional center to the film, but dims toward the end.

This is an intriguing setup. The hostage becomes the unknowing lover to the kidnapper. Afleck plays this out through great dialog. The characters are deeper than in most heist movies and Afleck gives them space and time to develop. Even the silences add to this film. The courtship provides an emotional center to the film, but dims toward the end.Afleck shows that he knows how to stage excellent action. The set-pieces escalate. The opening bank robbery sets the tone. Then there is an attack on an armored car that rolls into a massive and thrilling car chase through streets seemingly too narrow for such a chase. This must surely be one of the best chases of the year. The climax is a heist at Boston's crown jewel -- Fenway Park -- setting up a tremendous shoot out.

Three things make The Town a slightly inferior movie to Gone Baby Gone. First, the script is looser. It winds more linearly than its predecessor and has less emotional subtext. Second, it is harder to engage an audience to root for a violent criminal than it is to side with a local good guy. It seems almost morally wrong to want MacRay, a thief and a killer, to get away from the FBI. But the FBI agents are virtually comicatures; certainly the scenes of their investigative methods are superficial. The focus is clearly on the crooks. And third, the moral dilemmas are missing. Gone Baby Gone had two massive morality questions that caused us to reflect on what we would have done in similar circumstances.

Yet some moral thoughts come in the themes of choice and change. A key question revolves around the choices we can take. MacRay thinks he can choose to leave his town and start anew. But his erstwhile boss and crime lord, the rake-like florist Fergie (Pete Postlethwaite), won't let him go, threatening all those around him. Then, when MacRay determines to teach another low-life thug a lesson for terrorising his new girlfriend, he invites Coughlin along. Telling him he must choose to come and do violence without ever asking why, Coughlin jumps at this chance and choice. But, loose cannon that he is, he chooses to go above and beyond and risk more than MacRay wants.

Choice. What choices do we really have? Afleck and MacRay would say we have little choice. Much of life is controlled for us by others. They have power over us. In contrast, Eli (The Book of Eli) offered an alternative thought: "We always have a choice." Indeed, there is always a choice. We just may not like the consequences that go along with that choice. Bad choices got MacRay into crime when opportunity gave him a way out of Charlestown earlier. Is there a way out?

Perhaps the biggest question this film asks is if we can change and at what cost. With all the cards stacked against MacRay, can he morph and move on? At one point he asks, "No matter how much you change, you still have to pay the price for the things you've done." His Irish-catholic conscience troubles him for his evil deeds. The wages of sin must be paid.

Biblically, there is some truth here. We are all held accountable for our actions. "The wages of sin is death" (Rom. 6:23) and that is a price that must be paid. Yet, Jesus has himself paid that price for us on the cross. The sinless one (Heb. 4:15) has taken our sin on himself so that we might be freed from the consequences. Grace allows us to take up his offer of forgiveness and liberation. We do not need to beat ourselves up, as MacRay did, watching and wondering when the sins of our past will catch up with us. No, we can experience real change if we allow Jesus to become part of our life.

Yet, there are still consequences for sin and crime. Even with the forgiveness of Christ we should still expect to pay an earthly price. Change is not easy. Change is costly. Will we count the cost? Will we embrace change? We must, if we want to move forward and grow, not be caught up in the vicious cycle of an unforgiven and slowly dying existence.

Copyright ©2010, Martin Baggs

Thomas adds to the explanation in a voice-over, "In seven days, God created the world. And in seven seconds, I shattered mine." Seven becomes the critical number in the film.

Thomas adds to the explanation in a voice-over, "In seven days, God created the world. And in seven seconds, I shattered mine." Seven becomes the critical number in the film. Moreover, the Bible looks at humankind from God's perspective. It is not a pretty sight. All have turned away from God and are considered broken and damaged (Rom. 3:12). None are good in the sense that God desires (Rom. 3:10). There may be relative levels of goodness, but that begs the question of how we determine the basic level. No, our nature has been affected by the fall and we are not good until we receive a new nature through Christ (2 Cor. 5:17). "All have sinned and fall short of the glory of God" (Rom. 3:23).

Moreover, the Bible looks at humankind from God's perspective. It is not a pretty sight. All have turned away from God and are considered broken and damaged (Rom. 3:12). None are good in the sense that God desires (Rom. 3:10). There may be relative levels of goodness, but that begs the question of how we determine the basic level. No, our nature has been affected by the fall and we are not good until we receive a new nature through Christ (2 Cor. 5:17). "All have sinned and fall short of the glory of God" (Rom. 3:23). Whether he is helping Emily or Ezra (Woody Harrelson), another on his list, Thomas is seeking self-redemption. He is looking for forgiveness from a hideous sin. He wants to buy this forgiveness and expunge the guilt that is driving, even consuming, him.

Whether he is helping Emily or Ezra (Woody Harrelson), another on his list, Thomas is seeking self-redemption. He is looking for forgiveness from a hideous sin. He wants to buy this forgiveness and expunge the guilt that is driving, even consuming, him.

One of the keys to the movie comes in the form of Jellon Lamb (John Hurt), a sophisticated but drunk bounty hunter on the trail of the Burns brothers. Speaking to Charley in an empty tavern, Lamb says: "We are white men, sir, not beasts." And in another scene, Stanley proclaims, "I will civilize this land."

One of the keys to the movie comes in the form of Jellon Lamb (John Hurt), a sophisticated but drunk bounty hunter on the trail of the Burns brothers. Speaking to Charley in an empty tavern, Lamb says: "We are white men, sir, not beasts." And in another scene, Stanley proclaims, "I will civilize this land."

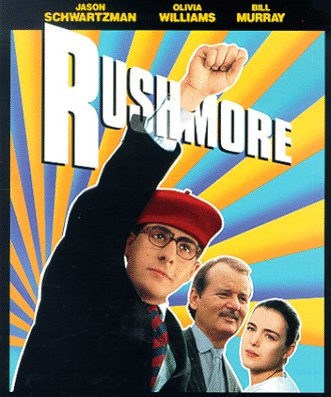

Rushmore centers on three characters: Max Fischer (

Rushmore centers on three characters: Max Fischer (

Between these two philosophies sits Rosemary. Younger than Herman, she is too old for Max's amorous intentions. (As mature as he thinks he is, he is just a child still.) She has experienced loss and has adopted a resigned view of life. She does not chase anything, but seems more accepting of what comes at her. But when it is both Herman and Max, she sees their love as youthful, even juvenile, telling Max, "You know, you and Herman deserve each other. Your'e both little children." Love can do that. It revitalizes. It sparks life into a cynical and cold heart. In this case it ignites friendly war that results in expulsion and competition. As Herman says, "She's my Rushmore."

Between these two philosophies sits Rosemary. Younger than Herman, she is too old for Max's amorous intentions. (As mature as he thinks he is, he is just a child still.) She has experienced loss and has adopted a resigned view of life. She does not chase anything, but seems more accepting of what comes at her. But when it is both Herman and Max, she sees their love as youthful, even juvenile, telling Max, "You know, you and Herman deserve each other. Your'e both little children." Love can do that. It revitalizes. It sparks life into a cynical and cold heart. In this case it ignites friendly war that results in expulsion and competition. As Herman says, "She's my Rushmore." We can glean nuggets from each character, both positive and negative, to improve our own lives. We can spurn the cynicism of age that Herman presents. Instead, we can seek to retain some of the enthusiasm and youthful idealism like Max without becoming dewy-eyed dreamers seeing what is not there. And we can bring a sage acceptance of life and its calamities like Rosemary.

We can glean nuggets from each character, both positive and negative, to improve our own lives. We can spurn the cynicism of age that Herman presents. Instead, we can seek to retain some of the enthusiasm and youthful idealism like Max without becoming dewy-eyed dreamers seeing what is not there. And we can bring a sage acceptance of life and its calamities like Rosemary.

Landing in Wyoming for these two city-slickers is akin to moving to a third-world country, such is the culture shock. Their hosts in the backwoods are Clay (Sam Elliot) and Emma Wheeler (Mary Steenburgen), the local US Marshals. These are gun-totin' rednecks, who understand PETA to mean "People eating tasty animals."

Landing in Wyoming for these two city-slickers is akin to moving to a third-world country, such is the culture shock. Their hosts in the backwoods are Clay (Sam Elliot) and Emma Wheeler (Mary Steenburgen), the local US Marshals. These are gun-totin' rednecks, who understand PETA to mean "People eating tasty animals."

As Lisbeth and Blomkvist begin to decipher the clues, they point to a deeply buried secret in the Vanger family. One disappearance reveals another crime and then another, until murders stack up. As the two would-be detectives dig deeper they find themselves in danger of becoming victims of murder themselves.

As Lisbeth and Blomkvist begin to decipher the clues, they point to a deeply buried secret in the Vanger family. One disappearance reveals another crime and then another, until murders stack up. As the two would-be detectives dig deeper they find themselves in danger of becoming victims of murder themselves.