Director: David Fincher, 2010. (PG-13)

Ideas change the world. The Social Network tells the story of a recent idea that changed our world. Not so much a biopic or even history, Fincher's film is an imaginative retelling that may not get to the truth but lays out various perspectives and allows us to engage them, choosing for ourselves. We may never know the real truth, but life is like that.

The film opens in 2003, even before the titles, with two students in the "Thirsty Scholar Pub" in Boston. Mark Zuckerberg (Jesse Eisenberg, who looks surprisingly like the real-life Facebook-founder), a sophomore computer programming student at Harvard, is talking to his girlfriend. The speed of his speech makes it tough to follow and his abrupt changes in direction exacerbates this. Then his girlfriend tells him she is breaking up with him. He is stunned. He cannot understand why. He has the social skills of . . . well a gnat. Without wanting to, he alienates those he is with. He is not so much a nerd, he is an ass, a socially handicapped genius.

Going back to his dorm room, while drinking beer and blogging about his breakup, he creates in just hours a website, Facemash, which takes down the Harvard network. His prodigious exploits put him in the sights of the Winklevoss twins, two Olympian rowers who have an idea for an exclusive on-line network for Harvard students. Inviting Zuckerberg to join them on this business opportunity, he either steals their idea or has his own idea energized. Either way, he becomes obsessed with the concept. As he tells his friend, Eduardo Saverin (Andrew Garfield): "People wanna go online and check out their friends, so why not build a website that offers that. I'm talking about the entire social experience of college and putting it online." He conceives of "thefacebook".

Going back to his dorm room, while drinking beer and blogging about his breakup, he creates in just hours a website, Facemash, which takes down the Harvard network. His prodigious exploits put him in the sights of the Winklevoss twins, two Olympian rowers who have an idea for an exclusive on-line network for Harvard students. Inviting Zuckerberg to join them on this business opportunity, he either steals their idea or has his own idea energized. Either way, he becomes obsessed with the concept. As he tells his friend, Eduardo Saverin (Andrew Garfield): "People wanna go online and check out their friends, so why not build a website that offers that. I'm talking about the entire social experience of college and putting it online." He conceives of "thefacebook".Here, indeed, is the intended target audience for Zuckerberg's initial idea. But it has gone way beyond that. Facebook now has over 500 million users, more than the population of the United States. And in a little less than a decade, Zuckerberg has gone from a dorm-dwelling dork to the youngest billionaire in history. There is certainly a story here. But which one is it?

Fincher moves from crime stories (Se7en, Zodiac) to this anarchic tale of social revolution by way of Fight Club and Benjamin Button. As a traditional narrative, highlighting the rise of Zuckerberg on the jet stream of technology, this would have been nothing more than social commentary. But with Aaron Sorkin's (A Few Good Men) adroit screenplay, excellent acting from relative unknowns, and with Fincher's decision to retain the story's ambiguity, this becomes an award-winning and compelling movie.

The Social Network cuts between the development of the Facebook idea and the deposition by the various key "inventors" as the now-rich Zuckerberg is sued by former friend Saverin as well as the twins.

In the backstory, Zuckerberg turns to Saverin for cash to finance the idea. And Saverin comes through, with $1000 now and more later. In return, he is offered the position of CFO of this fledgling company. But as the exclusive site, initially restricted to those with an harvard.edu email address, takes off, Saverin hungers to monetize it through advertising. But that would be uncool. Meanwhile, the twins ponder the gentlemanliness of suing a fellow Harvardian while simultaneously bemoaning their plight of missing their life-defining opportunity.

When Zuckerberg decides to expand from Harvard to more ivy league schools and then to Stanford, he appears on the radar of Sean Parker (Justin Timberlake). Parker, of course, was the founder of Napster, the visionary who came up with the idea of digital downloads and almost single-handedly initiated the collapse of records as we knew them. (At least that's the story here. And really, who buys music at Tower Records anymore?) This leads to a meeting with Mr. Cool himself in California, where Zuckerberg immediately likes him and Saverin dislikes him. Parker offers one piece of advice, "Drop the 'the'. Just 'Facebook'. It's cleaner." This stuck. So did he. As Zuckerberg moves to California, Saverin went to New York to hustle advertising. But it was Parker who delivered the venture capitalists and in doing so became a stockholder, supplanting Saverin as Zuckerberg's business adviser.

When Zuckerberg decides to expand from Harvard to more ivy league schools and then to Stanford, he appears on the radar of Sean Parker (Justin Timberlake). Parker, of course, was the founder of Napster, the visionary who came up with the idea of digital downloads and almost single-handedly initiated the collapse of records as we knew them. (At least that's the story here. And really, who buys music at Tower Records anymore?) This leads to a meeting with Mr. Cool himself in California, where Zuckerberg immediately likes him and Saverin dislikes him. Parker offers one piece of advice, "Drop the 'the'. Just 'Facebook'. It's cleaner." This stuck. So did he. As Zuckerberg moves to California, Saverin went to New York to hustle advertising. But it was Parker who delivered the venture capitalists and in doing so became a stockholder, supplanting Saverin as Zuckerberg's business adviser.How much of all this is true is unclear. But visionary Parker observed, "we lived in farms, then we lived in cities, and now we're gonna live on the internet!" That was true. And Zuckerberg picked up this vision and added it to his growing concept, ultimately making it come true. How many of us spend hours on the internet on the Facebook site? What started as a club for students, exploded worldwide. In my family of six, four of us have accounts, one wants one and only one prefers to live life in reality, not in cyberspace.

No one can dispute that Zuckerberg has transformed the social experience. We have gone from writing letters to email. Now we have added text messaging, tweets, and facebooking to the mix. His vision to add relationship status, photographs and videos to Facebook means that we can instantly upload documentation of tonight's party. We can snap a photo and post it almost before we can say "cheese". Is this good? Hard to say. It just is what it is. It certainly adds a new perspective to privacy, or lack of it. We now live on-line, through our facebook accounts.

At the heart of the film, if not the reality, is Zuckerberg's craving to belong. Unlike Groucho Marx' famous quip, "I don't care to belong to any club that will have me as a member," Zuckerberg wants to join an exclusive club. But he never does. When his friend gets invited in, he is visibly joyless. Rather than "rejoice with those who rejoice" (Rom. 12:15) he sulks because he is not the one. Desperately wanting to be on the inside, he creates the ultimate insider club: Facebook. He beomes the consummate anti-celebrity. With more money than almost anyone on the globe, he is perhaps least likely to be recognized by anyone on the globe.

Like Zuckerberg, we all crave to belong. We all want acceptance. In Jesus we can find this acceptance, this belonging. The community we desire is available to us in the church, the family that Christ formed (Col. 1:18). Some would argue that this community is hypocritical and superficial. And to some degree this is true. But it remains, nevertheless, the social and spiritual network devised by the creator of this world. And its inclusivity allows any to come (Matt. 11:28). All it takes is the desire to come to Jesus to experience what he offers: real life (Jn. 1:10), not virtual life.

Zuckerberg is certainly a visionary, whether he stole the idea or not. A social outsider and community rebel, he bears some comparison to Jesus, himself a social outsider. Two thousand years ago Jesus brought an idea to an exclusive community. He came to the Jews with the concept of a kingdom where the poor would be rich, the meek would be heirs, the persecuted would be rewarded (Matt. 5:2-12). Such a vision labelled him a rebel. And at an age not much beyond Zuckerberg's, Jesus was "unfriended" in the worst way possible: crucifixion (Jn. 19:16). But like Zuckerberg's vision, Jesus' has not gone away. His kingdom remains, albeit as an emerging one that will be fully realized at some point. A new social network and experience will come some day. Are you ready to accept Jesus' friend request?

Zuckerberg is certainly a visionary, whether he stole the idea or not. A social outsider and community rebel, he bears some comparison to Jesus, himself a social outsider. Two thousand years ago Jesus brought an idea to an exclusive community. He came to the Jews with the concept of a kingdom where the poor would be rich, the meek would be heirs, the persecuted would be rewarded (Matt. 5:2-12). Such a vision labelled him a rebel. And at an age not much beyond Zuckerberg's, Jesus was "unfriended" in the worst way possible: crucifixion (Jn. 19:16). But like Zuckerberg's vision, Jesus' has not gone away. His kingdom remains, albeit as an emerging one that will be fully realized at some point. A new social network and experience will come some day. Are you ready to accept Jesus' friend request? Copyright ©2010, Martin Baggs

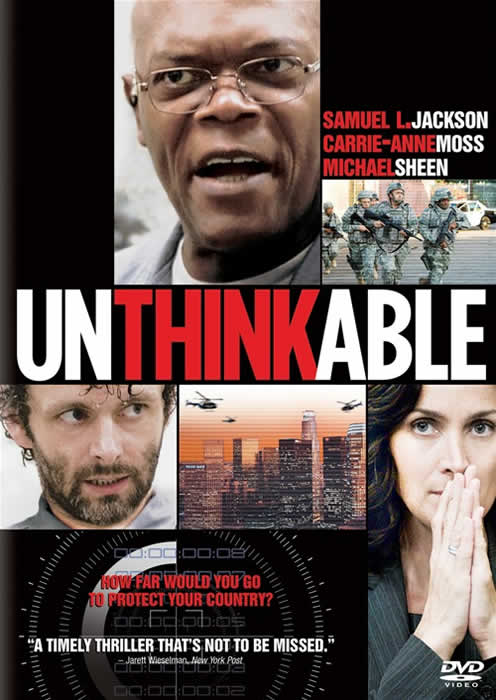

But Younger is no innocent Savior. He is a terrorist who will kill to achieve his ends. In the duel that his interactions with H and Brody becomes, he turns the question on those who have strapped him in the chair. Yelling, face flushed, "I'm not a coward. I chose to meet my oppressors face to face. You call me a barbarian. Then what are you? This is not about me. It's about you." Brody, more than H or Younger, becomes the person whose morality is in question. Younger and H won't change, but will she?

But Younger is no innocent Savior. He is a terrorist who will kill to achieve his ends. In the duel that his interactions with H and Brody becomes, he turns the question on those who have strapped him in the chair. Yelling, face flushed, "I'm not a coward. I chose to meet my oppressors face to face. You call me a barbarian. Then what are you? This is not about me. It's about you." Brody, more than H or Younger, becomes the person whose morality is in question. Younger and H won't change, but will she?

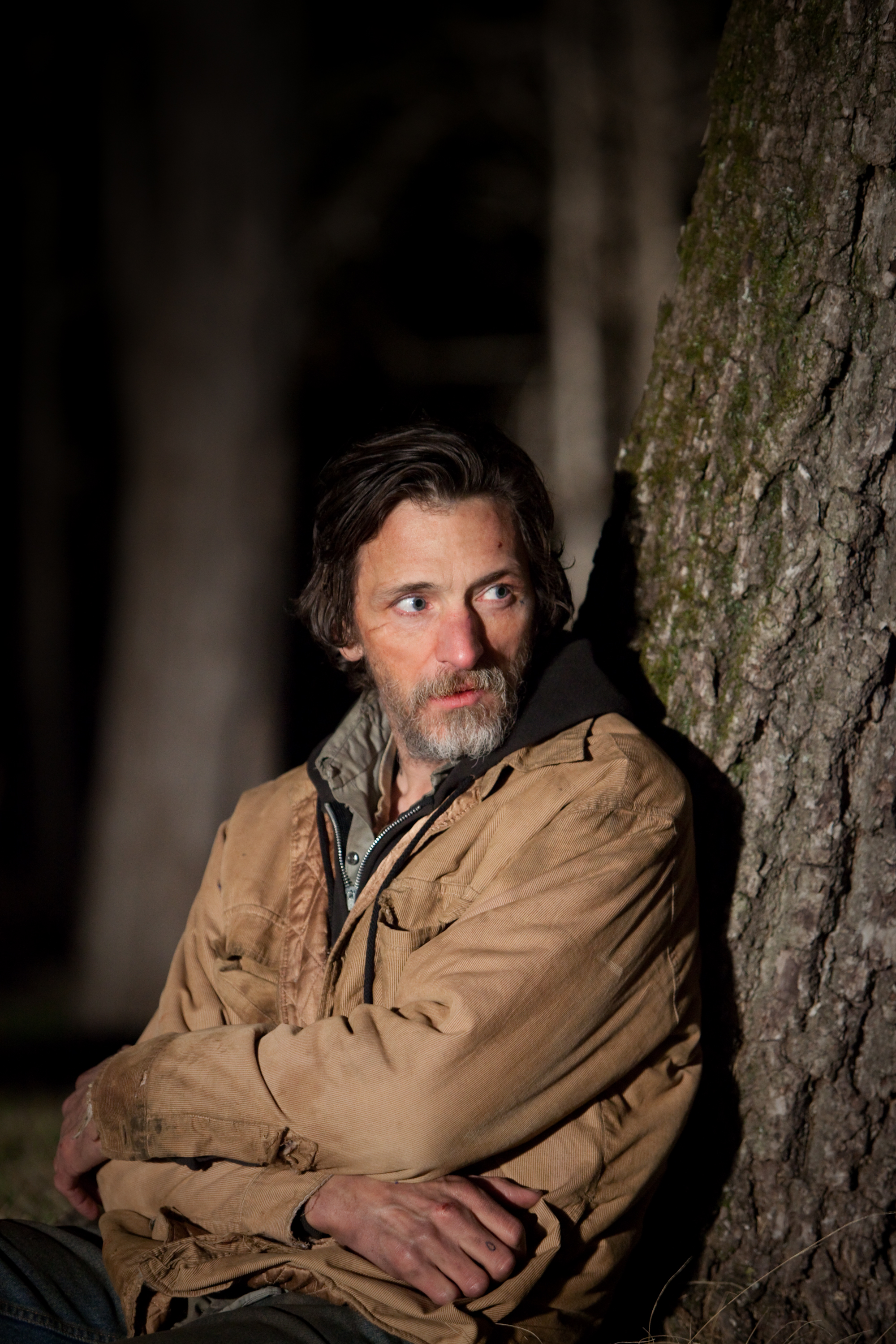

Setting out alone, without even a vehicle, Ree begins her quest to find her father. As a meth cooker, he has few friends in the underworld of the crystal methamphetamine subculture. But as she begins asking around, it seems everyone wants her to shut up and stop messing in their business. It is an ugly world with violence threatening at evey turn.

Setting out alone, without even a vehicle, Ree begins her quest to find her father. As a meth cooker, he has few friends in the underworld of the crystal methamphetamine subculture. But as she begins asking around, it seems everyone wants her to shut up and stop messing in their business. It is an ugly world with violence threatening at evey turn.

The second segment begins with Joker in Nam, outside the war zone. The first interaction between him, a fellow soldier, and a prostitute paints a picture of the situation. The locals see the G.I.s as opportunities: either to make a quick buck or to steal from them. They are not the liberating heroes they were in Europe twenty years earlier.

The second segment begins with Joker in Nam, outside the war zone. The first interaction between him, a fellow soldier, and a prostitute paints a picture of the situation. The locals see the G.I.s as opportunities: either to make a quick buck or to steal from them. They are not the liberating heroes they were in Europe twenty years earlier.

Much of the first part of the film shows Max's childhood (Freddy Highmore as the young Max), with summers spent with his uncle in France. It is there that he learned to drink wine and play chess and tennis. It is there, with this effervescent but commitment-challenged old man that Max learns lessons that carry over into his adult career.

Much of the first part of the film shows Max's childhood (Freddy Highmore as the young Max), with summers spent with his uncle in France. It is there that he learned to drink wine and play chess and tennis. It is there, with this effervescent but commitment-challenged old man that Max learns lessons that carry over into his adult career. The older Max seems to have forgotten this lesson, and does not entertain losing. He wants victories and money. So, when he goes to France to see his inheritance his focus is on a quick trip and an even quicker sale. He has forgotten the charm of the French countryside and the charms of his old uncle. But places trigger memories, good and bad. One woman asks him, "Are your memories of my father [Henry] good?" and Max replies wistfully, "No they are extraordinary. My uncle loved women, although no one for a long time, and he never married. He loved England, yet lived in France. He was an adventurer, yet all my memories take place within 100 steps of this spot."

The older Max seems to have forgotten this lesson, and does not entertain losing. He wants victories and money. So, when he goes to France to see his inheritance his focus is on a quick trip and an even quicker sale. He has forgotten the charm of the French countryside and the charms of his old uncle. But places trigger memories, good and bad. One woman asks him, "Are your memories of my father [Henry] good?" and Max replies wistfully, "No they are extraordinary. My uncle loved women, although no one for a long time, and he never married. He loved England, yet lived in France. He was an adventurer, yet all my memories take place within 100 steps of this spot."

The band has broken up. Gary is working for Paul composing music for commercials, selling out his artistic creative talent, replacing it with artless copying of familiar tunes. Clearly, his job is going nowhere. His girlfriend Dora (Gwyneth Paltrow, the director's sister) is tired and bored with him. Their love-life is so absent, he reads "The Idiot's Guide to the Middle East" in bed and has to put that aside to allow Dora to get her sleep. Can it get any worse?

The band has broken up. Gary is working for Paul composing music for commercials, selling out his artistic creative talent, replacing it with artless copying of familiar tunes. Clearly, his job is going nowhere. His girlfriend Dora (Gwyneth Paltrow, the director's sister) is tired and bored with him. Their love-life is so absent, he reads "The Idiot's Guide to the Middle East" in bed and has to put that aside to allow Dora to get her sleep. Can it get any worse? Then Gary meets Anna (Penelope Cruz,

Then Gary meets Anna (Penelope Cruz,  Most of us at some time want to escape the humdrum reality of our lives. Some try drugs, others adventurous recreation. But if dreams become our reality, then we will pursue them instead. They leave us at the center of our universe. But they are an avoidance of reality. Like the old men in Inception who sleep for days to live in their very own dream-worlds, reality has lost its lustre and anything we can substitute we will.

Most of us at some time want to escape the humdrum reality of our lives. Some try drugs, others adventurous recreation. But if dreams become our reality, then we will pursue them instead. They leave us at the center of our universe. But they are an avoidance of reality. Like the old men in Inception who sleep for days to live in their very own dream-worlds, reality has lost its lustre and anything we can substitute we will.