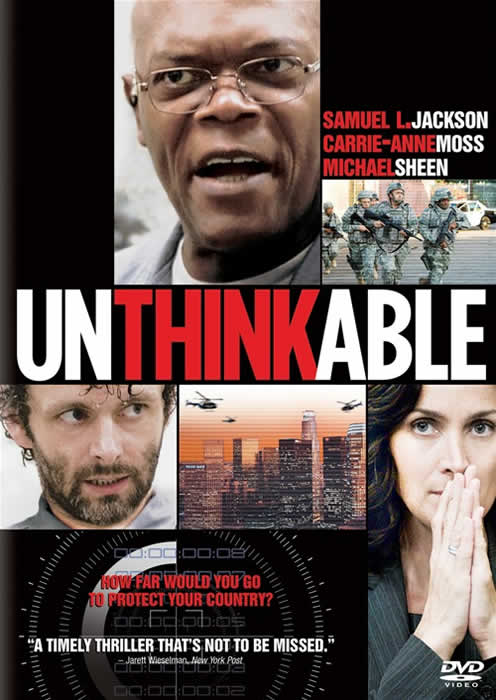

Director: Gregor Jordan, 2010. (R)

“My name is Yusuf Mohammad, my former name is Steven Arthur Younger, and I have planted three nuclear bombs across the country. They will detonate unless my demands are met.” The opening scene is captured on a home video camera and portends an intense thriller.

When Younger (Michael Sheen, The Damned United) sends this tape, with video of all three bombs, to the government, teh FBI is brought in to find the bombs. Heading up this effort is Agent Helen Brody (Carrie-Anne Moss, The Matrix). But when she finds out that Younger is already in custody, she joins CIA "consultant" Henry "H" Humphries (Samuel L. Jackson), an interrogation specialist she has already encountered. Heads butted there, now they must join together if they are to save the millions of lives that are in danger.

Our first glimpse of Younger's captivity shows him hanging by his arms in a special cell-compartment in a high school gymnasium, being beaten by an army interrogator. This torture is nothing compared to what awaits him at H's hands. Demanding complete control, H takes over and immediately opens up his tool-case of knives, choppers, hypodermics and more. This is Gitmo-meets-suburbia in a plausible deniability inquisition that nobody in office knows about; in other words, "it never happened".

Unthinkable deserves its direct-to-DVD genealogy. The three stars do what they can but the script limits them. The dialog veers from dumbed-down, in case we don't quite follow the authorities' investigations, to didactic when points are being made. Though it works as a psychological thriller, it pours so much violence into the interrogation scenes that it is almost torture-porn. Those with squeamish stomachs be warned: stay away, or at least be ready to turn your heads numerous times throughout. And it seems more clumsy polemic than censurable pleasure.

As H ratchets up the torture, the central question emerges: do the ends justify the means? H whispers in the ear of the suffering terrorist: "There is no H. and Younger . . . there's only victory and defeat. The winner gets to take the moral high-ground, because they get to write the history books. The loser . . . just loses." This is relative morality.

Do the ends ever justify the means? Unthinkable makes it clear that the pain and possible killing of one man is outweighed by the saving of the millions of innocent US lives that hang in the balance. This was exactly the thinking that Caiaphas expounded 2000 years ago. As high priest, while Jesus was alive, he said: “You do not realize that it is better for you that one man die for the people than that the whole nation perish" (Jn. 11:50). He sentenced the innocent Christ to death to save the Jewish nation. In reality, Jesus died to save more than this one nation. He died to save all of us (1 Tim. 4:10).

But Younger is no innocent Savior. He is a terrorist who will kill to achieve his ends. In the duel that his interactions with H and Brody becomes, he turns the question on those who have strapped him in the chair. Yelling, face flushed, "I'm not a coward. I chose to meet my oppressors face to face. You call me a barbarian. Then what are you? This is not about me. It's about you." Brody, more than H or Younger, becomes the person whose morality is in question. Younger and H won't change, but will she?

But Younger is no innocent Savior. He is a terrorist who will kill to achieve his ends. In the duel that his interactions with H and Brody becomes, he turns the question on those who have strapped him in the chair. Yelling, face flushed, "I'm not a coward. I chose to meet my oppressors face to face. You call me a barbarian. Then what are you? This is not about me. It's about you." Brody, more than H or Younger, becomes the person whose morality is in question. Younger and H won't change, but will she?If the ends apparently justify the means, then the means become the vehicle for becoming those we despise. By resorting to torture, the torturer becomes like the terrorist. How far will H (and Brody) go to save the innocent? That underscores the dilemma. In a war without rules, the Geneva convention is moot. The combatants on one side see no difference between soldiers and civilians. H understands this ("There are no innocent children") and is like Younger. But if we stoop to this level aren't we as guilty as Younger? Is there any place here for morality and ethics? Can there be a right and wrong, or will might always rule?

Jesus taught us to turn the other cheek (Matt. 5:39), and he lived in brutal times where terrorists were strung up on crosses with no trial. Victory does come through violence, as the Romans showed and as H desired. But this is a transient triumph. The true victory only comes in the true kingdom, the kingdom of heaven where behavior is paradoxical and summed in the beattitudes (Matt. 5:3-12).

Toward the end, as the interrogation approaches its climax, H screams at Younger: "Youssef! Do you believe I can do this?" Brody, squirming, shouts, "H, he believes it, he believes it!" But H goes on, "Faith is not enough, he has to know it!" Brody: "He knows it!" H: "Knowing is not enough! He has to see it."

Here H lays out the progression of faith leading to knowledge and knowledge requiring sight. It is the opposite of living by faith and not by sight (2 Cor. 5:7). Thomas, the disciple of Jesus, had to see to believe: “Unless I see the nail marks in his hands and put my finger where the nails were, and put my hand into his side, I will not believe" (Jn. 20:25). But when he finally did see the resurrected Christ, Jesus told him, “Because you have seen me, you have believed; blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed" (Jn. 20:29). We are in the latter category. We believe without seeing. Our faith is enough.

At the conclusion of Unthinkable, as H is prepared to do the unthinkable, all hell breaks loose. With various characters revealing their own means of accomplishing the common ends, the film's ethic winds up in Brody's hands. Like her we all face a decision of our own. Will we do the unthinkable of living for our own glory and pleasure, turning away from the one who could save us? Or will we look at his hands and feet and, "seeing," believe in him?

Copyright ©2010, Martin Baggs

No comments:

Post a Comment