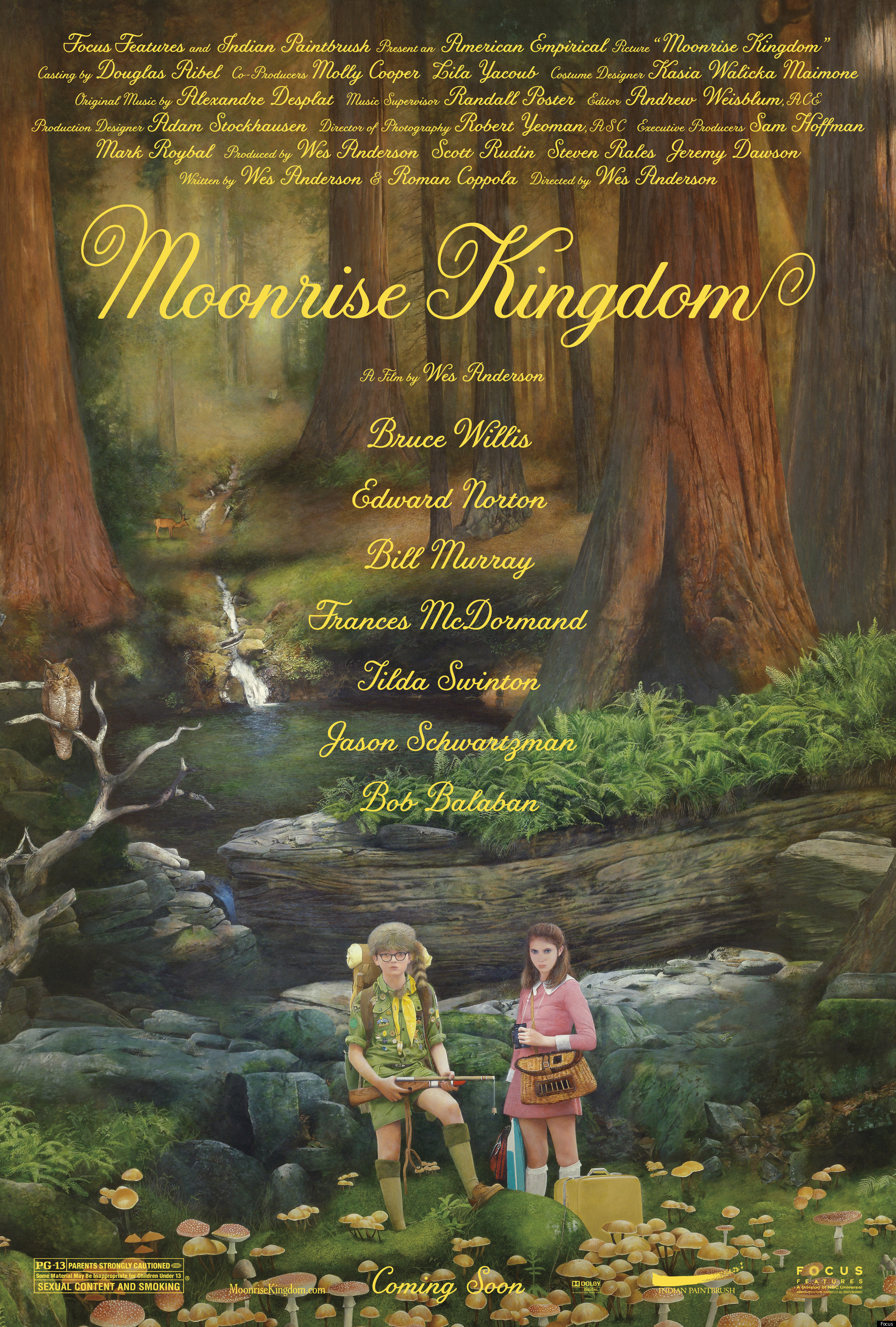

Director: Wes Anderson, 2012 (PG-13)

Offbeat and quirky, Moonrise Kingdom is quintessential

Anderson, even down to the actors he uses (Bill Murray, Jason Schwartzman). It

is a tale of two lovers. But these lovers are adolescent misfits shunned by

their families.

Set on an island off the coast of New England in the 1960s,

Anderson creates a world of his own. This is a roadless realm of few cars, and

one town, a community that must pull together in the face of danger and need.

The need comes when the two young lovers run away. The danger comes when the

storm of the century approaches.

Sam (Jared Gilman) is a bespectacled Khaki Scout, an orphan

who is hated by his fellow scouts for no apparent reason. Suzy (Kara Hayward)

is the eldest daughter of two lawyers Walt (Murray) and Laura Bishop (Frances

McDormand). The separation of her parents, even within the family, is shown in

the opening scenes as they are in separate rooms communicating through a

bull-horn.

Through flashback we see Sam and Suzy’s budding relationship

emerge from their “love-at-first sight” beginnings when she was a bird in the

school pageant performing Noah’s Ark. Through love letters penned to one

another, they conceive a plan to meet in a meadow and run away across the

island to a bay, where they rename the island Moonrise Kingdom.

When they run away, Scout Master Ward (Edward Norton) calls

the police chief Captain Sharp (Bruce Willis) and together with the scout troop

and islanders they form up a rescue-hunting party. With the searchers getting

closer, so is the storm.

Anderson juxtaposes the wonders of young love, puppy love

really, with the cynicism or clichés of mature love, particularly through the

dialog of Sam and Suzy. Despite their youth, they talk like people decades

older even when their subject is pre-adolescent. For example, when Sam is

preparing to share a tent with Suzy, he says: “It’s possible I may wet the bed

by the way. Later, I mean.” And Suzy, declaring to her parents, “We’re in love.

We just want to be together. What’s wrong with that?” We’ve heard this line in

any number of movies, yet never from a 12 year-old.

Young love and loss of innocence form the central thesis of

the film. The relationship that Sam and Suzy share, mostly through letters, is

a flowering of love with all its pains and pleasures. But it is an innocent

love that exalts in dancing in underwear on a deserted beach all, and then

discovers the tastes of tongue in French kissing. But innocence does not last,

if it was really ever there. And the beginning of act 2, along with the

discovery of Mrs. Bishop’s affair and the actions of Sam’s foster parents,

usher in that post-innocence era. Adolescence indeed does transition a person

from child to teen but at the cost of his or her innocence.

Biblically, innocence was lost at the Fall (Gen. 3), when

humanity succumbed to the temptations to seek Godlikeness. Despite this, people

typically feel that young children retain a certain innocence, a form of moral

unaccountability. But none would argue that innocence is lost around the

teenage years.

With innocence lost, a form of salvation is necessary. Here

in Moonrise Kingdom Sam and Suzy need to be saved, both for themselves and for

their community. And Anderson gives us a form of salvation by water. The flood

that was depicted theatrically earlier in the film befalls the town, destroying

homes and harbor. But the community is saved by taking refuge in the ark: the

Church of St Jack. And only when the community pulls together can Sam and Suzy

escape the separation that Child Services (Tilda Swinton) wants to enforce,

along with mandatory electroshock therapy. Indeed, at the climax Sam faces up

to his particular need for a father.

These two themes, of salvation by water and the fatherless

finding a father, are eminently biblical.

The flood in Noah’s time (Gen. 7-8) brought destruction and

death through the deluge. But the ark provided salvation for Noah and his

family. Later, Jesus came by water and blood (1 Jn. 5:6) and brought his own

form of salvation to all. This salvation offers forgiveness of sin and absence

of condemnation (Rom. 8:1), all through the washing in the blood of the Son

(Rev. 7:14). Sam and Suzy’s baptism echoes Noah’s baptism and points to our

baptism into the saving ark of Jesus Christ.

The flood in Noah’s time (Gen. 7-8) brought destruction and

death through the deluge. But the ark provided salvation for Noah and his

family. Later, Jesus came by water and blood (1 Jn. 5:6) and brought his own

form of salvation to all. This salvation offers forgiveness of sin and absence

of condemnation (Rom. 8:1), all through the washing in the blood of the Son

(Rev. 7:14). Sam and Suzy’s baptism echoes Noah’s baptism and points to our

baptism into the saving ark of Jesus Christ.

Moreover, we are all creations of God, made in his image. He

is our father. When we reject or ignore this, we live life fatherless, orphaned

like Sam. We harbor a deep need to feel a father’s love. The Bible has almost

40 verses that call out to the fatherless in the nation of Israel, all pointing

out that God watches over the fatherless (Ps. 146:9). But in the New Testament

we come across a God that wants us to call him Father. In the most famous

prayer in the Bible, Jesus tells us to pray, “Our Father . . . “ (Matt. 6:9).

He tells us that if we love and follow him, the father will come into us (Jn.

14:23). And if we recognize this burning need and receive him, we instantly

enter into his family and become true children of God (Jn. 1:12), now ready to

call God our Father. The fatherless come home into community.

Anderson has made another gem, both precocious and poignant.

His typical style of meticulous and visually colorful backdrops is there. His

atemporal landscape is almost magical, a fantasy that is grounded in the

reality of childhood hope and irresponsibility. And it all plays out with an

understated gravity and nostalgia that belie the depth of the themes involved.

It’s not hysterically funny. But that’s not Anderson’s style. But it is

well-acted and captures the recklessness and openness of childhood friendships,

even if they are not true love!

Copyright ©2013, Martin Baggs

No comments:

Post a Comment