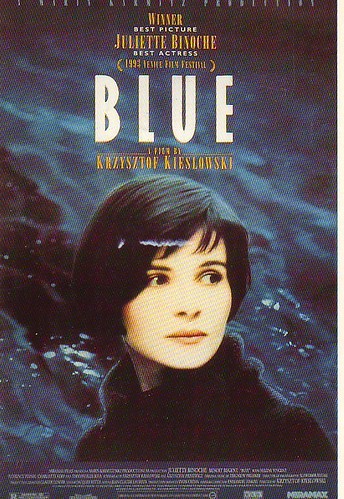

Director: Krzysztof Kieslowski, 1993.

Blue is the first film of Kieslowski's tri-color series, and a tour-de-force it is indeed. Although not true sequels, they are loosely connected in that several characters appear in cameos and some scenes are repeated from a different perspective. Based on the colors of the Tri-color, the French flag, blue, white and red, the themes of this flag represent the themes of this trio: liberty, equality and fraternity. In particular, Blue focuses on liberty and loss.

At the very beginning of Blue, Julie (Juliette Binoche, The Flight of the Red Balloon, Dan in Real Life) and her family are involved in a car accident. When she wakes she is in a hospital room alone, and her husband and daughter are dead. Breaking into the nurse's room, she steals a bottle of pills and pops them all into her mouth. But she cannot go through with this obvious suicide attempt. Yet she cannot deal with the loss and the ensuing grief. And while in her hospital bed she cannot be at the funeral for her two loved ones; since her husband is an acclaimed composer, the service is broadcast on TV and she has to watch on a small portable set.

When she is released from the hospital, Julie goes to the country farmhouse her family owns and clears out belongings and memories. She sheds no tears, she pushes aside her pain, she isolates her memories. She says, "Now I have only one thing left to do: nothing. I don't want any belongings, any memories. No friends, no love. Those are all traps." The only thing she takes is a blue hanging crystalline mobile/lamp that presumably belonged to her daughter.

Julie moves to Paris, changes her name to avoid being found and rents an apartment. She has various funds enough to live, but no vocational future to keep her alive. Although she did not commit suicide, her withdrawal from the world is tantamount to emotional, spiritual and relational suicide.

Blue is an artistic composition. It is a visual exploration of Julie's character. Kieslowski uses little dialog and long extended shots to convey inner changes and struggles. For example, Julie holds a sugar cube dipped into coffee until it is saturated. In another scene, a coffee cup and saucer are the only objects in the frame emphasizing the passage of hours as Julie sits and soaks in the Parisian cafe. There is little plot, but this movie is a stunning achievement of the use of color and light, complemented by music.

Julie hangs her blue mobile in her new apartment. Jeffrey Overstreet, in his book "Through a Screen Darkly," comments extensively on Blue. He says these stones "are like strands of suspended crystalline tears, pieces of sharp-edged grief that Julie has not been able to express." For me, they seem to be a metaphor for her past and its memories. In her farmhouse, she tore some and let them fall, cascading, onto the wooden floor. Yet she was not willing to let them all go, despite her apparent intention. She repressed her memories but still carried them with her into Paris. When her neighbor, an exotic dancer, approaches this mobile, the fear and sense of violation is clear on Julie's face. These are her memories, they cannot be shared.

Julie hangs her blue mobile in her new apartment. Jeffrey Overstreet, in his book "Through a Screen Darkly," comments extensively on Blue. He says these stones "are like strands of suspended crystalline tears, pieces of sharp-edged grief that Julie has not been able to express." For me, they seem to be a metaphor for her past and its memories. In her farmhouse, she tore some and let them fall, cascading, onto the wooden floor. Yet she was not willing to let them all go, despite her apparent intention. She repressed her memories but still carried them with her into Paris. When her neighbor, an exotic dancer, approaches this mobile, the fear and sense of violation is clear on Julie's face. These are her memories, they cannot be shared.There are several key scenes that are informative and transformative for Julie. While Julie sits on a bench, an old lady hobbles along the street clutching an empty bottle, trying to recycle it. But the depository slot is too high. This is a visual picture of life alone with no one to help. Another picture of aloneness and loss is Julie's mother, living in a care-home, her memory gone. As Julie was trying to let go of her memories, her mother was already there, not knowing Julie's name. Was this what she really wanted, a life without friends, a life without memories?

In another scene she is swimming alone in a blue-lit pool. Instead of emerging from the water, she suddenly curls up in a ball, a fetal position, and submerges herself. This is a form of rebirth. The new Julie is waiting in this amniotic fluid for a moment to emerge and face life. She is not yet ready; but her birth is imminent.

When her neighbor calls her to the exotic dance club late one night, Julie sees herself on the TV. She realizes that her husband's final unfinished composition for the unification of Europe, which she thought she had destroyed, is being finished by her friend Olivier (Benoît Régent). She had abandoned this symphony but it would not abandon her. Indeed, a busker had told her, "You have to hold onto something," and finally she realizes it is the music which will liberate her. The symphony will come out; it must be finished.

When her neighbor calls her to the exotic dance club late one night, Julie sees herself on the TV. She realizes that her husband's final unfinished composition for the unification of Europe, which she thought she had destroyed, is being finished by her friend Olivier (Benoît Régent). She had abandoned this symphony but it would not abandon her. Indeed, a busker had told her, "You have to hold onto something," and finally she realizes it is the music which will liberate her. The symphony will come out; it must be finished.Unlike Audrey who deals with her loss in Things We Lost in the Fire by reaching out for human relationship, Julie deals with hers by running away. Julie tried to find freedom and emotional liberty by starting over, isolating herself as a nameless face in a nameless suburb. But, as Overstreet says, "the more Julie tries to break free, the more she imprisons herself." Her solitude is not liberating. It can be. As God tells us, "Be still and know I am God" (Psa. 46:10) and we can discover much about ourselves and our maker in that contemplative quietness, if we listen. But Julie is running and not listening.

In contrast, when she understands that she must face her loss and move on, the music of the symphony under-construction becomes her healing balm. Again, Kieslowski uses creative camerawork and technique to let us experience the music being written as Julie would experience it, and there is a beautiful mystery about this. There is grace in this healing, and this grace works its way into and through Julie in how she comes to deal graciously with those around her, even those who have hurt her. Grace is even present in the finale, with a choir singing 1 Corinthians 13 in Greek as the orchestral composition hits its climax.

In contrast, when she understands that she must face her loss and move on, the music of the symphony under-construction becomes her healing balm. Again, Kieslowski uses creative camerawork and technique to let us experience the music being written as Julie would experience it, and there is a beautiful mystery about this. There is grace in this healing, and this grace works its way into and through Julie in how she comes to deal graciously with those around her, even those who have hurt her. Grace is even present in the finale, with a choir singing 1 Corinthians 13 in Greek as the orchestral composition hits its climax.Throughout the film the color blue crops up, highlighting the mood of Julie's grief. A blue light occurs frequently, when Julie is caught by some fleeting memory. Accompanied by strains of an orchestral composition, possibly her husband's, these blue screen shots hold for several seconds while Julie is clearly processing something. The meaning of this blue light is unexplained. For Overstreet, it is the spirit of reunification of broken things. Clearly, Julie needs to reconnect with the broken things in her life. But I think it is more the grief breaking into her consciousness so it might be processed. Perhaps it is the common grace of God's goodness that is forcing Julie to think about life and move from her escapist prison of personal solitary confinement to the true liberty of living in community.

As a movie about loss and grief, it shows that grief cannot be repressed. It is a reality. It requires a journey through the darkness to emerge once more in the light of life. The early part of grieving needs time. In the Bible Job lost all his children (Job 1:18). When his friends came to be with him, the first seven days they simply sat in silence beside him comforting him with their presence (Job 2:17). Words were not present or needed. But when they started to talk, to analyze, they made Job's life worse. Likewise, in Lars and the Real Girl, when Lars lost his beloved Bianca the elderly ladies of his church came to sit and knit beside him. Just being there is what counts in this phase of grief.

But grief has to move beyond this. At some point the griever must choose life and hold onto something, as Julie reached out to music. Death is part of life. We must embrace this truth and be ready to move through the valley of the shadow of death to once more to get to life.

Copyright ©2009, Martin Baggs

I had never heard of this movie before, but after reading your blog I am so excited to see it!

ReplyDeleteCharles, Boston