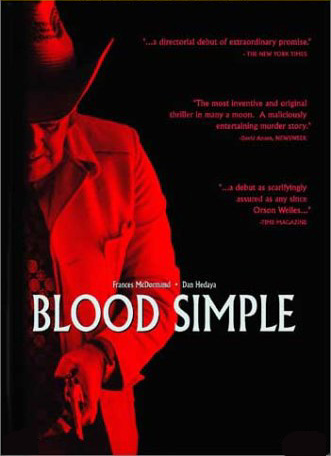

Director: Joel Coen, 1984.

A quarter century ago a pair of fresh young film-makers hit the scene. They were the brothers Coen. This was their first film, but it contains seeds of the greatness that was to come, with foreshadowings of both Fargo and their Best Picture Oscar, No Country for Old Men.

Like No Country, Blood Simple is set in Texas. But where the later film used the harsh landscape almost as a character, here is is used simply as a backdrop for a film noir. Like any good noir, the private eye provides voice-over narration. Well, at least for the opening scene, but that's all that's needed to provide context for what is about to unfold:

The world is full o' complainers. An' the fact is, nothin' comes with a guarantee. Now I don't care if you're the pope of Rome, President of the United States or Man of the Year; somethin' can all go wrong. Now go on ahead, y'know, complain, tell your problems to your neighbor, ask for help, 'n watch him fly. Now, in Russia, they got it mapped out so that everyone pulls for everyone else... that's the theory, anyway. But what I know about is Texas, an' down here... you're on your own.Two major themes emerge from this initial soliloquy: guarantees and isolation.

Like most film noir, the premise is clear: cuckolded husband hires a man to kill his wife. But the characters are complex: a cheating wife and a jealous husband, a committed lover and a jaded detective.

Like most film noir, the premise is clear: cuckolded husband hires a man to kill his wife. But the characters are complex: a cheating wife and a jealous husband, a committed lover and a jaded detective.When Marty (Dan Hedaya) finds out that his wife Abby (Frances McDormand) is sleeping with his employee Ray (John Getz), he solicits the private eye who discovered the adulterous pair in the act, Loren Visser (M. Emmet Walsh), to murder them both. A simple, if sinful, proposition, yet Marty doesn't count on the depths of deceit of the detective, whose greed outstrips his guile. Double-cross follows double-cross until it is unclear whose heart is the coldest.

Of the four main characters, Visser is the simplest and the wickedest. Contrary to film noir norms, this private detective is no good guy. He is not even gray and shadowy. He is cold and cunning, manipulating and malevolent. Although he prefers to stay within the law, he has no conscience about crossing the line if the price is right. Honor and honesty are words absent from his phrasebook. The Coens even portray his evil with careful camera work that focuses on the sweat that slowly slides down his face and the flies that alight on his head. The diseases that the flies may carry are nothing compared to the wickedness that he harbors in his heart. This, combined with a satanic laugh, makes Visser a vile villain.

Of the four main characters, Visser is the simplest and the wickedest. Contrary to film noir norms, this private detective is no good guy. He is not even gray and shadowy. He is cold and cunning, manipulating and malevolent. Although he prefers to stay within the law, he has no conscience about crossing the line if the price is right. Honor and honesty are words absent from his phrasebook. The Coens even portray his evil with careful camera work that focuses on the sweat that slowly slides down his face and the flies that alight on his head. The diseases that the flies may carry are nothing compared to the wickedness that he harbors in his heart. This, combined with a satanic laugh, makes Visser a vile villain.Since Marty is the husband wronged, he might be the sympathetic hero. But he is loud and obnoxious, and a would-be murderer. He has no charm, no heart, only a love of money. He wants his pound of flesh. He wants his guarantees. But, "nothin' comes with a guarantee," and Marty finds out first-hand how true this is in painful and humiliating ways.

Speaking of guarantees, Benjamin Franklin once said, "in this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes." Even Jesus needed to pay taxes when he walked the earth, though he came up with the money in a miraculous manner (Matt. 17:27). And Jesus faced death, an ignominious penal death by crucifixion. The penalty, though, was not his but ours. Jesus died on our behalf to take the punishment for our sins, that we might find forgiveness and freedom to live in him (Eph. 1:7). Visser was wrong; life comes with a guarantee. We face a choice with two guaranteed outcomes: new life in Jesus (Matt. 25:34) or separation from God apart from him (Matt. 25:41, 46).

Unlike Marty, Abby is the real protagonist in this dark film. Though she sets the wheels in motion with her infidelities, she remains in the dark through most of the narrative. Separated from Marty, when Ray becomes guilt-crazed in a Macbethian manner, Abby realizes she has no one to turn to. She is isolated, on her own. And she does not really know what is happening around her.

Unlike Marty, Abby is the real protagonist in this dark film. Though she sets the wheels in motion with her infidelities, she remains in the dark through most of the narrative. Separated from Marty, when Ray becomes guilt-crazed in a Macbethian manner, Abby realizes she has no one to turn to. She is isolated, on her own. And she does not really know what is happening around her.Abby may be alone, but we have a guarantee of community and fellowship with Jesus. When we trust him, we are brought into his family as children of God (). Moreover, we become members of the body of Christ, the church universal, even if we are not attending a local church. Best of all, Jesus promises never to leave us or forsake us (). Others might walk away, leaving us like Abby to face our enemies apart from other people. But Jesus will always be with us.

And then there's Ray. When we first meet Ray he seems just a small-town hick, harmless enough. But the way of the adultress is death, as Proverbs says (Prov. 2:16-19). His choices cause him to slide slowly down the slippery slope. But it his love, misplaced though it may be, that drives him there. Visser, the film's anti-conscience, speaks to Marty in one scene about getting our hands dirty. "That's the test, ain't it? Test of true love." Ray in his ignorance misreads the signs and seeks to save his "true love" Abby by getting his hands down and dirty. But at what cost.

And then there's Ray. When we first meet Ray he seems just a small-town hick, harmless enough. But the way of the adultress is death, as Proverbs says (Prov. 2:16-19). His choices cause him to slide slowly down the slippery slope. But it his love, misplaced though it may be, that drives him there. Visser, the film's anti-conscience, speaks to Marty in one scene about getting our hands dirty. "That's the test, ain't it? Test of true love." Ray in his ignorance misreads the signs and seeks to save his "true love" Abby by getting his hands down and dirty. But at what cost.Jesus got his hands dirty for us. He humbled himself by clothing his godness in humanity (Phil. 2:6-7). Then he had his hands pierced, nailed to the rough wood of a cross of execution (Acts 2:23). He died to save his true love, humanity; you and me. What we could not do, he did for us. And unlike Ray, Jesus was able to complete his mission, saving us in his love. Our life comes through Jesus' blood simple.

Copyright ©2009, Martin Baggs

When the tapes start to open closets containing skeletons and dreams unearth images of the past, Daniel suspects a culprit. He remarks to Anne, "I have a hunch." But he refuses to share more than this with her. "Can't you tell me?" she shouts. "No, because it's only a hunch." This leaves her furious. Haneke uses this pivotal scene to spring the trap that will catch Georges and force his hand. Anne despairingly cries out, "You never heard of trust?"

When the tapes start to open closets containing skeletons and dreams unearth images of the past, Daniel suspects a culprit. He remarks to Anne, "I have a hunch." But he refuses to share more than this with her. "Can't you tell me?" she shouts. "No, because it's only a hunch." This leaves her furious. Haneke uses this pivotal scene to spring the trap that will catch Georges and force his hand. Anne despairingly cries out, "You never heard of trust?" As Georges goes looking for the truth he resurrects long-forgotten memories, and he finds something he wished had remained lost. Not wishing to share his discovery with Anne, he further damages their fragile trust by lying to her, a lie that will come back to haunt him.

As Georges goes looking for the truth he resurrects long-forgotten memories, and he finds something he wished had remained lost. Not wishing to share his discovery with Anne, he further damages their fragile trust by lying to her, a lie that will come back to haunt him.

Furthermore, John is told at one point, "You can't protect us and save yourself." That was true of Jesus. As his life on earth moved inexorably toward Golgotha and crucifixion, he could save himself or he could save the world. But he could not do both. One had to give. He chose to voluntarily take our place and die on the cross. What sacrifice.

Furthermore, John is told at one point, "You can't protect us and save yourself." That was true of Jesus. As his life on earth moved inexorably toward Golgotha and crucifixion, he could save himself or he could save the world. But he could not do both. One had to give. He chose to voluntarily take our place and die on the cross. What sacrifice.

There are some famously memorable lines in The Holy Grail. The Dead Collector yells, "Bring out yer dead," a spoof on the black death. (And the old man who pleads, "I'm not dead.") Then there is the wonderfully mixed up logic for determining if a woman (Connie Booth, one-time wife of John Cleese) is a witch ("If she weighed the same as a duck. . . she's made of wood. . . And therefore. . . A witch"). Of course, who can forget the Black Knight and his "flesh wound,"or the Knights who say Ni.

There are some famously memorable lines in The Holy Grail. The Dead Collector yells, "Bring out yer dead," a spoof on the black death. (And the old man who pleads, "I'm not dead.") Then there is the wonderfully mixed up logic for determining if a woman (Connie Booth, one-time wife of John Cleese) is a witch ("If she weighed the same as a duck. . . she's made of wood. . . And therefore. . . A witch"). Of course, who can forget the Black Knight and his "flesh wound,"or the Knights who say Ni. When King Arthur succeeds in gathering a motley group of knights to follow him, including Sir Galahad the pure, Sir Bedevere the quiet, Sir Lancelot the brave, and Sir Robin the not-quite-so-brave-as-Sir-Lancelot, he gets a second quest. God appears in the clouds, an animated figure, and speaks to him, telling him to go in search of the holy grail. (The holy grail is the chalice that Jesus drank from and shared with his disciples during the last supper -- Lk. 22:17). But in this interchange, God is decidedly grumpy:

When King Arthur succeeds in gathering a motley group of knights to follow him, including Sir Galahad the pure, Sir Bedevere the quiet, Sir Lancelot the brave, and Sir Robin the not-quite-so-brave-as-Sir-Lancelot, he gets a second quest. God appears in the clouds, an animated figure, and speaks to him, telling him to go in search of the holy grail. (The holy grail is the chalice that Jesus drank from and shared with his disciples during the last supper -- Lk. 22:17). But in this interchange, God is decidedly grumpy: Speaking of the Bible, King Arthur makes implicit reference to this holy text when he needs help. Facing the dreaded killer rabbit, only the "Holy Hand Grenade of Antioch" will suffice. But the king has a problem: "How does it work?" When no one can answer him, Arthur declares, "Consult the Book of Armaments." And Brother Maynard, one of the attending priests, opens the book, "Armaments, chapter two, verses nine through twenty-one."

Speaking of the Bible, King Arthur makes implicit reference to this holy text when he needs help. Facing the dreaded killer rabbit, only the "Holy Hand Grenade of Antioch" will suffice. But the king has a problem: "How does it work?" When no one can answer him, Arthur declares, "Consult the Book of Armaments." And Brother Maynard, one of the attending priests, opens the book, "Armaments, chapter two, verses nine through twenty-one."

Rose, the former head cheerleader, is still in love with former boyfriend, high-school star quarterback Mac (Steve Zahn). But he is married with children. He is using Rose and will never leave his wife. Yet Rose is too weak to face this truth. She knows it, because she tries to motivate herself with a bathroom mirror pep-talk: "You are strong, you are powerful, you can do anything, you are a winner." Mere words are not enough. She needs a crisis and a catharsis.

Rose, the former head cheerleader, is still in love with former boyfriend, high-school star quarterback Mac (Steve Zahn). But he is married with children. He is using Rose and will never leave his wife. Yet Rose is too weak to face this truth. She knows it, because she tries to motivate herself with a bathroom mirror pep-talk: "You are strong, you are powerful, you can do anything, you are a winner." Mere words are not enough. She needs a crisis and a catharsis. Sunshine Cleaning is a comic drama focusing on dark subject matter -- suicide. The leads play well together and have good chemistry. As a quirky low-budget film, it is short but feels longer. It employs a little too many stereotypes for a typical indie movie, and the comedy feels strained in places. But it is of interest for its characters and offers two terrific scenes worth pondering.

Sunshine Cleaning is a comic drama focusing on dark subject matter -- suicide. The leads play well together and have good chemistry. As a quirky low-budget film, it is short but feels longer. It employs a little too many stereotypes for a typical indie movie, and the comedy feels strained in places. But it is of interest for its characters and offers two terrific scenes worth pondering.

To combat this, we can be less sensitive and more guarded. We can be self-controlled (1 Thess. 5:6), not allowing our fickle emotions to rule our actions. And, on the other side of the fence, we can be more sensitive to others. We can look more gently and caringly on our siblings, our children, even our parents. Are there signs of loneliness or withdrawal? Are we spending enough time with them, listening to them, being with them, showing our love to them? This is critically important. Just as Jesus came and spent time with us, showing us in his life, as well as his death (Rom. 5:8), that he loved us, so we show our love to others with our time, not our pocketbooks.

To combat this, we can be less sensitive and more guarded. We can be self-controlled (1 Thess. 5:6), not allowing our fickle emotions to rule our actions. And, on the other side of the fence, we can be more sensitive to others. We can look more gently and caringly on our siblings, our children, even our parents. Are there signs of loneliness or withdrawal? Are we spending enough time with them, listening to them, being with them, showing our love to them? This is critically important. Just as Jesus came and spent time with us, showing us in his life, as well as his death (Rom. 5:8), that he loved us, so we show our love to others with our time, not our pocketbooks. When Max sees these wild things, one of them, Carol (voiced by James Gandolfini) is having a temper tantrum, destroying things because his friend has left him. This is a mirror-image of Max. Realizing this is a kindred soul, Max emerges from his hiding place. But he is discovered. To protect himself, he declares himself a king, a thing these wild things want. The first order of business for King Max: "Let the wild rumpus start." Then, when Carol shows him this wild and deserted island, he tells Max, "You're the owner of this world."

When Max sees these wild things, one of them, Carol (voiced by James Gandolfini) is having a temper tantrum, destroying things because his friend has left him. This is a mirror-image of Max. Realizing this is a kindred soul, Max emerges from his hiding place. But he is discovered. To protect himself, he declares himself a king, a thing these wild things want. The first order of business for King Max: "Let the wild rumpus start." Then, when Carol shows him this wild and deserted island, he tells Max, "You're the owner of this world." As King, Max wanted to bring fun to this family. When Carol gets excited and says, "It's going to be a place where only the things you want to happen, would happen," he is tapping into this belief that a king can make us happy by making good things happen. And Max replies, "We could totally build a place like that!" And Max does bring this group together, with fun and a grand mission to build a fort. But like the snowball scene, when Max' wild fun with the wild things gets out of hand, frustration and fighting take over. Then family tensions and jealousies recur. Even a king cannot solve all the wild things' problems with fun.

As King, Max wanted to bring fun to this family. When Carol gets excited and says, "It's going to be a place where only the things you want to happen, would happen," he is tapping into this belief that a king can make us happy by making good things happen. And Max replies, "We could totally build a place like that!" And Max does bring this group together, with fun and a grand mission to build a fort. But like the snowball scene, when Max' wild fun with the wild things gets out of hand, frustration and fighting take over. Then family tensions and jealousies recur. Even a king cannot solve all the wild things' problems with fun.

When he meets his apartment neighbor Stephanie (Charlotte Gainsbourg), he is smitten with her pixie-like friend Zoé (Emma de Caunes). In their initial interaction, he shows them his new 3-D glasses. "You can see real life in 3-D," he tells them. Stephanie, puzzled, retorts, "Isn't life already in 3-D?" But apparently not for Stéphane: "Yeah, but come on."

When he meets his apartment neighbor Stephanie (Charlotte Gainsbourg), he is smitten with her pixie-like friend Zoé (Emma de Caunes). In their initial interaction, he shows them his new 3-D glasses. "You can see real life in 3-D," he tells them. Stephanie, puzzled, retorts, "Isn't life already in 3-D?" But apparently not for Stéphane: "Yeah, but come on." Gondry brings some terrific ideas into this film. There are some wonderful moments where the magic of Stéphane's dream-world become reality, such as with his floating clouds and cellophane water. His "one-second time machine" is a curious concept. Would a machine that could transport us one-second into either the past or the future be of any value? It seems strangely irrelevant but apropos to his mindset. And it is this kind of quirkiness that will either resonate or repulse the viewer.

Gondry brings some terrific ideas into this film. There are some wonderful moments where the magic of Stéphane's dream-world become reality, such as with his floating clouds and cellophane water. His "one-second time machine" is a curious concept. Would a machine that could transport us one-second into either the past or the future be of any value? It seems strangely irrelevant but apropos to his mindset. And it is this kind of quirkiness that will either resonate or repulse the viewer. As romances go, this is a far cry from Hollywood. Yet, it is a far cry from reality, too. Romance is a beautiful and mysterious quality but if it only leads to sex then it is superficial and seductive. Romance is designed by God to lead to marriage, which is his plan for the union of man and woman (Gen. 2:24). When we walk in the path of God's ideal, we will find reality is actually better than fictitious dreams. Romance may pale, but a marriage founded in Jesus will endure in love.

As romances go, this is a far cry from Hollywood. Yet, it is a far cry from reality, too. Romance is a beautiful and mysterious quality but if it only leads to sex then it is superficial and seductive. Romance is designed by God to lead to marriage, which is his plan for the union of man and woman (Gen. 2:24). When we walk in the path of God's ideal, we will find reality is actually better than fictitious dreams. Romance may pale, but a marriage founded in Jesus will endure in love.

Tomo and Marek's lives intersect at a working class cafe, where Marek is looking at photos of Maria (Elisa Lasowski), the pretty French waitress. When Tomo steals the photos and is then caught by Marek, an unlikely friendship begins.

Tomo and Marek's lives intersect at a working class cafe, where Marek is looking at photos of Maria (Elisa Lasowski), the pretty French waitress. When Tomo steals the photos and is then caught by Marek, an unlikely friendship begins. But boredom hits the two protagonists. As Tomo and Marek's friendship develops, they spend their days together, hanging out through their boredom. Boredom can easily lead to mischief or crime. Throw in hope, though, and dreams can emerge. For Marek and Tomo, their dream is of Maria. Teenage hormones produce infatuation masquerading as love.

But boredom hits the two protagonists. As Tomo and Marek's friendship develops, they spend their days together, hanging out through their boredom. Boredom can easily lead to mischief or crime. Throw in hope, though, and dreams can emerge. For Marek and Tomo, their dream is of Maria. Teenage hormones produce infatuation masquerading as love. With no Maria, Tomo and Marek get plastered on the wine themselves. Indeed, drinking is evident throughout. Marek's father, at one point, says to his Polish buddies, "Let's get wasted." That is his idea of how to spend an evening. It is not surprising that his drinking to excess leads to his son's underage drinking. The sins of the father are passed on to the son. We learn from those we look up to, especially our parents.

With no Maria, Tomo and Marek get plastered on the wine themselves. Indeed, drinking is evident throughout. Marek's father, at one point, says to his Polish buddies, "Let's get wasted." That is his idea of how to spend an evening. It is not surprising that his drinking to excess leads to his son's underage drinking. The sins of the father are passed on to the son. We learn from those we look up to, especially our parents.

There are now almost two million aliens living in squalor. Their shanty town is infested with hatred and crime. Along the way, Nigerian gangsters have moved into exploit these aliens, and are carving out huge profits in illicit trade. Poverty and crime ignite prejudice and judgmentalism amongst the human population of "Joburg." They no longer see opportunity in this interaction with an alien civilization. They merely see the crime and violence that has been born from the ghetto. They refer to the aliens as "prawns," a derogatory term. The aliens have become de-alienized.

There are now almost two million aliens living in squalor. Their shanty town is infested with hatred and crime. Along the way, Nigerian gangsters have moved into exploit these aliens, and are carving out huge profits in illicit trade. Poverty and crime ignite prejudice and judgmentalism amongst the human population of "Joburg." They no longer see opportunity in this interaction with an alien civilization. They merely see the crime and violence that has been born from the ghetto. They refer to the aliens as "prawns," a derogatory term. The aliens have become de-alienized. Obviously we are not better than other people. Living in suburbs with other white skinned people does not make the blacks of the slums inferior. God made us all equally in his image (Gen. 1:26) regardless of skin color. In fact, diversity is actually more likely to lead to healthier and more creative living because our blind-spots will be exposed for correction.

Obviously we are not better than other people. Living in suburbs with other white skinned people does not make the blacks of the slums inferior. God made us all equally in his image (Gen. 1:26) regardless of skin color. In fact, diversity is actually more likely to lead to healthier and more creative living because our blind-spots will be exposed for correction. Wikus is selected as the MNU officer to lead the project and descends on the fenced-in ghetto along with a phalanx of military protectors. Going door-to-door, he must get a signature from each alien to "legalize" this immoral action. When something goes wrong, Wikus finds himself an object of interest to MNU, not for himself or his service, but because he can suddenly fire the alien weapons. He has become a unique commodity, more precious than gold or oil. He is exploited for financial gain without any due process or regard for his personal interests or rights.

Wikus is selected as the MNU officer to lead the project and descends on the fenced-in ghetto along with a phalanx of military protectors. Going door-to-door, he must get a signature from each alien to "legalize" this immoral action. When something goes wrong, Wikus finds himself an object of interest to MNU, not for himself or his service, but because he can suddenly fire the alien weapons. He has become a unique commodity, more precious than gold or oil. He is exploited for financial gain without any due process or regard for his personal interests or rights. When District 9 moves into its second half, Wikus is a man on the run, like Dr. Kimble in The Fugitive. It starts to feel like a Hollywood action film. The documentary approach takes second fiddle to straight up normal cinema. And here the film loses something. But it still carries us along with the tension and suspense of Wikus' character development.

When District 9 moves into its second half, Wikus is a man on the run, like Dr. Kimble in The Fugitive. It starts to feel like a Hollywood action film. The documentary approach takes second fiddle to straight up normal cinema. And here the film loses something. But it still carries us along with the tension and suspense of Wikus' character development.

At the wake in his home in a dilapidated Detroit neighborhood that has seen better days, Kowalski realizes he is alone now. His sons are strangers to him. He has no real relationship with them or with his grandchildren. Only his dog, Daisy, and his prize Gran Torino, a muscle car in perfect condition, give him any joy.

At the wake in his home in a dilapidated Detroit neighborhood that has seen better days, Kowalski realizes he is alone now. His sons are strangers to him. He has no real relationship with them or with his grandchildren. Only his dog, Daisy, and his prize Gran Torino, a muscle car in perfect condition, give him any joy. There are some very funny scenes in Gran Torino which give it some levity. Most concern Kowalski's slow understanding of the Hmong community. As Kowalski and Thao start to interact, he becomes a mentor for the lad. He teaches him how to be a man in America: "Take these three items, some WD-40, a vise grip, and a roll of duct tape. Any man worth his salt can fix almost any problem with this stuff alone." How true! Then, he teaches him how men banter with mock-insults in an hilarious interchange with his barber (John Carroll Lynch,

There are some very funny scenes in Gran Torino which give it some levity. Most concern Kowalski's slow understanding of the Hmong community. As Kowalski and Thao start to interact, he becomes a mentor for the lad. He teaches him how to be a man in America: "Take these three items, some WD-40, a vise grip, and a roll of duct tape. Any man worth his salt can fix almost any problem with this stuff alone." How true! Then, he teaches him how men banter with mock-insults in an hilarious interchange with his barber (John Carroll Lynch,  As the film progresses, Kowalski, who has been in all kinds of situations in war, finds himself in a place he never dreamt he would be: his Hmong neighbor's kitchen eating Hmong food amongst a party of non-English speakers. Surprisingly, he mutters to himself, "I've got more in common with these goddamned gooks than my own spoiled-rotten family." He has connected with the Hmong. Despite the sadness implicit in this self-understanding, it underscores the need for relationship. God has made us with a need to live in community (Rom. 12:16). That community need not be homogeneous, of one kind. It is probably better to be heterogeneous, made up of a rainbow of colors and creeds. We are called to love those around us (Matt. 5:44, Jn. 13:34).

As the film progresses, Kowalski, who has been in all kinds of situations in war, finds himself in a place he never dreamt he would be: his Hmong neighbor's kitchen eating Hmong food amongst a party of non-English speakers. Surprisingly, he mutters to himself, "I've got more in common with these goddamned gooks than my own spoiled-rotten family." He has connected with the Hmong. Despite the sadness implicit in this self-understanding, it underscores the need for relationship. God has made us with a need to live in community (Rom. 12:16). That community need not be homogeneous, of one kind. It is probably better to be heterogeneous, made up of a rainbow of colors and creeds. We are called to love those around us (Matt. 5:44, Jn. 13:34). Kowalski's relationship with the young priest is another key to the film and to the character arc. His initial view of Father Janovich is not good: "I think you're an overeducated 27-year-old virgin who likes to hold the hands of superstitious old ladies and promise them everlasting life." But Janovich is persistent, both to befriend him and to invite his confession. And he offers a cutting observation to Walt: "Sounds like you know more about death than you do about living." Kowalski has dealt death before, and is now living a dead life. He has not really lived in half a century.

Kowalski's relationship with the young priest is another key to the film and to the character arc. His initial view of Father Janovich is not good: "I think you're an overeducated 27-year-old virgin who likes to hold the hands of superstitious old ladies and promise them everlasting life." But Janovich is persistent, both to befriend him and to invite his confession. And he offers a cutting observation to Walt: "Sounds like you know more about death than you do about living." Kowalski has dealt death before, and is now living a dead life. He has not really lived in half a century.