Director: Avi Nesher, 2007.

Who doesn't have some secret that should not be revealed? In Nesher's film three women have secrets that slowly emerge to transform their lives.

At the heart of the Israeli film The Secrets is Naomi (Ania Bukstein), the daughter of a prominent rabbi. With her mother dead, she is to be married off to an arrogant rabbi-wannabe. But she is not ready for that. A devout orthodox Jew and brilliant student, she imagines herself the first female rabbi. That would be quite something in the traditional, yet repressive culture that she is immersed in. To postpone marriage, she suggests to her father that she spend a year in Jewish seminary in the mountains studying. Surprisingly he agrees.

When she arrives at the "Truth and Knowledge" seminary in the ancient Kabalistic town of Safed she meets Michel (Michal Shtamler in her film debut), a free-spirited student who is set on challenging all the rules and maintaining her individuality. These two will forge an unlikely friendship that will change both.

The third key female is Anouk (the iconic French actress, Fanny Ardant). A middle-aged woman, she has returned to this isolated town to die. She has terminal cancer, and a shocking secret. Assigned to bring her groceries as a mission of compassion, Michel and Naomi come to terms with one another through these visits. Michel is the only French-speaker, and since Anouk cannot speak Hebrew, that leaves Naomi isolated.

The third key female is Anouk (the iconic French actress, Fanny Ardant). A middle-aged woman, she has returned to this isolated town to die. She has terminal cancer, and a shocking secret. Assigned to bring her groceries as a mission of compassion, Michel and Naomi come to terms with one another through these visits. Michel is the only French-speaker, and since Anouk cannot speak Hebrew, that leaves Naomi isolated. Their approach to this ministry underscores the differences between Naomi and Michel. Naomi's desire is to perform the ministry by the letter of the law: deliver the groceries, store them and go. This is much as her religion dictates. In contrast, Michel goes further. She sees compassion as reaching the inner person, not just the outer shell. She befriends Anouk, and their conversations begin to unpack the secret that has been spiritually eating Anouk up like the cancer that has ravaged her body.

This introduces two ethical insights. First, it challenges the notion of religion as a simple list of rules and regulations. Noami has lived her life religiously, doing what is defined as right. She does the grocery chore at the command of the head of the seminary. But in keeping the letter of the law she is missing the underlying spirit of the law. Michal, the non-traditionalist, understands this. She ministers to the heart and in doing so initiates change: in Anouk and in the two students.

This introduces two ethical insights. First, it challenges the notion of religion as a simple list of rules and regulations. Noami has lived her life religiously, doing what is defined as right. She does the grocery chore at the command of the head of the seminary. But in keeping the letter of the law she is missing the underlying spirit of the law. Michal, the non-traditionalist, understands this. She ministers to the heart and in doing so initiates change: in Anouk and in the two students. How often do we, even Bible-affirming followers of Jesus, seek to live our disciplined lives by keeping rules? We may have our own lists of dos and don'ts, or they may be suggested by our ministers. But Jesus said there is really only one commandment: to love God completely (Lk. 10:27). There is no complicated series of laws to ponder and strive to attain. Just love God. This is so much bigger than our little lists; it is a holistic lifestyle.

The second insight is centered on compassion. Michal reached Anouk by caring for her, by listening to her story. And as she did so, Anouk shared her guilty secret. Jesus realized this, too, when he added an appendix to the one law: "Love your neighbor as yourself" (Lk. 10:27). We do not love ourselves by simply keeping a list. We go beyond this. We look at our inner person, and feed and nurture our souls. Likewise, ministry that is focused on performance and numbers is often legalistic. Life-changing ministry focuses on compassion, on care, communicating love. This changes both giver and receiver alike.

The second insight is centered on compassion. Michal reached Anouk by caring for her, by listening to her story. And as she did so, Anouk shared her guilty secret. Jesus realized this, too, when he added an appendix to the one law: "Love your neighbor as yourself" (Lk. 10:27). We do not love ourselves by simply keeping a list. We go beyond this. We look at our inner person, and feed and nurture our souls. Likewise, ministry that is focused on performance and numbers is often legalistic. Life-changing ministry focuses on compassion, on care, communicating love. This changes both giver and receiver alike.As Anouk's friendship with these two students blossoms, she reveals her desire to come right with God before her death. Naomi, the more learned of the two, researches and creates several tikkun, Kabbalistic Jewish purification rituals that would cleanse her and restore her relationship with God. One, a cleansing in a sacred pool, seems similar to the Christian sacrament of baptism. Anouk emerges from her submerging with a renewed zeal.

Indeed, Anouk's desperate desire for redemption parallels that of most people, if truth be told. We are all, in some way or another, separated from God (Isa. 59:2). When death comes knocking and we know we have little time left, this desire, dormant for decades perhaps, rises to the surface. Like soldiers offering foxhole prayers, people staring mortality in the eyes often realize their need to get right with God. Redemption is a heart-beat and simple prayer away. It does not require the elaborate rituals that Naomi takes Anouk through. Simply accepting the gift of grace that our savior Jesus offers is enough (Rev. 3:20). We can become children of God through a prayer of faith (Rom. 10:9-10), when we believe in his payment of our sin on the cross on our behalf (Heb. 9:15).

Instead of dealing with sin in this fashion, an alternate approach is evident in Naomi's life. As her secret emerges, she seeks the Jewish Scriptures for an answer and "finds" one. She rationalizes her sin away. We do this, too, when we find our answers, ignoring the clear and crisp words of God. Rationalizing sin is our way to create and control a god who is smaller than Yahweh, the one and only true God found in Scripture (Deut. 6:4).

As the movie winds towards its non-Hollywood ending, we find Naomi liberated from her repressive beliefs. The black clothes of her student days in the first half of the film are replaced with white garments. She is no longer repressed but is rejected by family and society. What a a price to pay for her "freedom." In contrast, we see Michel willing to compromise her individuality and accept a more traditional role in society. Their roles have been reversed.

As the movie winds towards its non-Hollywood ending, we find Naomi liberated from her repressive beliefs. The black clothes of her student days in the first half of the film are replaced with white garments. She is no longer repressed but is rejected by family and society. What a a price to pay for her "freedom." In contrast, we see Michel willing to compromise her individuality and accept a more traditional role in society. Their roles have been reversed.The Secrets is a slow-paced yet poignantly moving story of repression and forbidden love. But it leaves us focused on change. Are we changing for the better or the worse? Are we more like Naomi or Michel? Either way, have we come to terms with our God like Anouk? That may be our own most important secret.

Copyright ©2009, Martin Baggs

At the start, Snyder gives a montage of images that paint the history of America since WW2. Masked vigilantes emerged to watch over society. These so-called superheroes are merely men and women who are prepared to fight crime, for one reason or another. One image shows a group of these watchmen together at a retirement party. This party photo is a recreation of Leonardo Da Vinci's "The Last Supper" and is clearly painting the parallel to Christ and his disciples. Yet, missing from the picture is the Christ figure. He will show up later.

At the start, Snyder gives a montage of images that paint the history of America since WW2. Masked vigilantes emerged to watch over society. These so-called superheroes are merely men and women who are prepared to fight crime, for one reason or another. One image shows a group of these watchmen together at a retirement party. This party photo is a recreation of Leonardo Da Vinci's "The Last Supper" and is clearly painting the parallel to Christ and his disciples. Yet, missing from the picture is the Christ figure. He will show up later. Snyder paints a dark picture of humanity. The rule of mob law and the depravity of the superheroes themselves points to the savage nature of mankind. This is an exaggerated but sadly true picture of humanity. We are depraved (Jer. 17:9), we are tainted by sin. None has lived a righteous life (Rom. 3:10); all have turned away from God (Isa. 53:6).

Snyder paints a dark picture of humanity. The rule of mob law and the depravity of the superheroes themselves points to the savage nature of mankind. This is an exaggerated but sadly true picture of humanity. We are depraved (Jer. 17:9), we are tainted by sin. None has lived a righteous life (Rom. 3:10); all have turned away from God (Isa. 53:6). Although these superheroes want to make the world a better place, their motives are mixed and so are their methods. Rorschach lives with the principle, "Never compromise. Not even in the face of Armageddon." He wants to exercise justice on the unjust, the lowlife criminals, but he does so without mercy or compassion. There is nothing that separates him from those he is trying to rid society of. Justice is one thing, justice tempered with grace is quite another.

Although these superheroes want to make the world a better place, their motives are mixed and so are their methods. Rorschach lives with the principle, "Never compromise. Not even in the face of Armageddon." He wants to exercise justice on the unjust, the lowlife criminals, but he does so without mercy or compassion. There is nothing that separates him from those he is trying to rid society of. Justice is one thing, justice tempered with grace is quite another. Throughout Snyder intersperses brief vignettes showing us who the watchmen really are. Comedian, the first to die, is the only government-endorsed superhero. But, who watches the watchment? The Comedian is actually a psychopath who relishes societal violence as an opportunity for him to exercise violence on others. We see him enjoying the killing fields of Vietnam and showing no remorse while coldly gunning down a lover.

Throughout Snyder intersperses brief vignettes showing us who the watchmen really are. Comedian, the first to die, is the only government-endorsed superhero. But, who watches the watchment? The Comedian is actually a psychopath who relishes societal violence as an opportunity for him to exercise violence on others. We see him enjoying the killing fields of Vietnam and showing no remorse while coldly gunning down a lover. It is Dr. Manhattan who is the missing Christ-figure. Referring to him, one of his friends says, "I did not say there is a superman and he is American. I said there is a God and he is American." From superman to god, he is deified. And no wonder, he can see past, present and future. He can manipulate matter. He can materialize anywhere he wants. He can split into multiple beings, a veritable holy trinity of blue Jons.

It is Dr. Manhattan who is the missing Christ-figure. Referring to him, one of his friends says, "I did not say there is a superman and he is American. I said there is a God and he is American." From superman to god, he is deified. And no wonder, he can see past, present and future. He can manipulate matter. He can materialize anywhere he wants. He can split into multiple beings, a veritable holy trinity of blue Jons.

After their guide loses his way in the dense fog, a sudden firefight finds the two Bosnians in a no man's land trench between the two armies' front-lines, Ciki is wounded and Cera is apparently dead. When the Serbs send out two soldiers to scout out what happened, Nino is one of them. The other puts a "bouncing bomb" mine underneath the body of Cera to boobytrap the corpse, but a brief skirmish leaves this Serb dead and Nino wounded. These three wounded soldiers form the core around which Tanovic delivers his thoughts about war.

After their guide loses his way in the dense fog, a sudden firefight finds the two Bosnians in a no man's land trench between the two armies' front-lines, Ciki is wounded and Cera is apparently dead. When the Serbs send out two soldiers to scout out what happened, Nino is one of them. The other puts a "bouncing bomb" mine underneath the body of Cera to boobytrap the corpse, but a brief skirmish leaves this Serb dead and Nino wounded. These three wounded soldiers form the core around which Tanovic delivers his thoughts about war. The second moral concept is that might is right. The man holding the weapon becomes the man in the right as Ciki testifies. But might is right is an errant philosophy. Just because Ciki holds the rifle does not mean the Serbs started the war. He simply has the power to make the Serb say what he wants to hear or risk being killed. Might is right is simply wrong. When we misuse our might and power to make others say and do things we want, we are guilty of coercion and no better than the enemy who we think started the war.

The second moral concept is that might is right. The man holding the weapon becomes the man in the right as Ciki testifies. But might is right is an errant philosophy. Just because Ciki holds the rifle does not mean the Serbs started the war. He simply has the power to make the Serb say what he wants to hear or risk being killed. Might is right is simply wrong. When we misuse our might and power to make others say and do things we want, we are guilty of coercion and no better than the enemy who we think started the war.

When Castella and his wife Angélique (Christiane Millet) later go to the theater, he is once again bored, wishing to be elsewhere. He is a rich philistine, not appreciating the finer things in life. But his eye is caught by Clara (Anne Alvaro), the lead actress in the Greek tragedy and he gazes at her with rapt attention. Somehow, his artless heart has become alive to what is before him. She was the woman he failed to hire as an English teacher. Recognition dawns and so does the spark of life.

When Castella and his wife Angélique (Christiane Millet) later go to the theater, he is once again bored, wishing to be elsewhere. He is a rich philistine, not appreciating the finer things in life. But his eye is caught by Clara (Anne Alvaro), the lead actress in the Greek tragedy and he gazes at her with rapt attention. Somehow, his artless heart has become alive to what is before him. She was the woman he failed to hire as an English teacher. Recognition dawns and so does the spark of life. And then there are Manie (Jaoui) and Franck (Gérard Lanvin). She is a pretty barmaid who deals hash for a living. He is Castella's temporary bodyguard. Both have a cynical approach to love and relationships: casual sex is their choice. He boasts of his hundreds of conquests to the naive Bruno. She tells Franck that she approaches sex like a man: no love just physical union. But by the time the movie is over, they have found in each other someone so much like themselves that they are ready to change.

And then there are Manie (Jaoui) and Franck (Gérard Lanvin). She is a pretty barmaid who deals hash for a living. He is Castella's temporary bodyguard. Both have a cynical approach to love and relationships: casual sex is their choice. He boasts of his hundreds of conquests to the naive Bruno. She tells Franck that she approaches sex like a man: no love just physical union. But by the time the movie is over, they have found in each other someone so much like themselves that they are ready to change. Which brings us back to Castella and Clara. After he has gazed upon the beauty of her acting, he wants more. Castella becomes like a puppy in love, wanting to spend time with her, though he is clueless among her bohemian artist friends. She wants little to do with him, but this does not stop him. As he hangs with her, he begins to see art. His eyes are open as if for the first time. She, in turn, is 40 and wants love but cannot find it from the men around her. She cannot see what is in front of her face: Castella. Her preconceptions keep her closed off to this businessman.

Which brings us back to Castella and Clara. After he has gazed upon the beauty of her acting, he wants more. Castella becomes like a puppy in love, wanting to spend time with her, though he is clueless among her bohemian artist friends. She wants little to do with him, but this does not stop him. As he hangs with her, he begins to see art. His eyes are open as if for the first time. She, in turn, is 40 and wants love but cannot find it from the men around her. She cannot see what is in front of her face: Castella. Her preconceptions keep her closed off to this businessman.

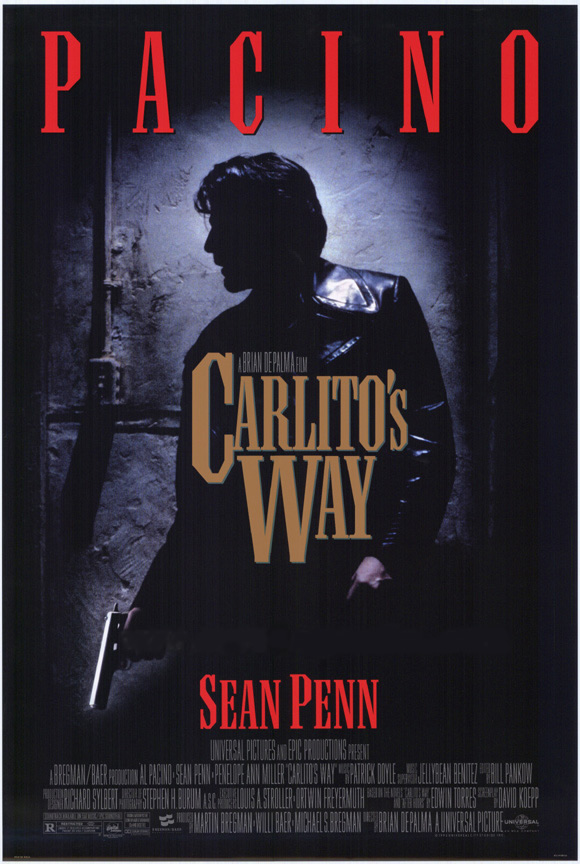

Carlito's reference to being born again takes us back to the first century conversation between Jesus and Nicodemus. Jesus told this Jewish leader, "I tell you the truth, no one can see the kingdom of God unless he is born again" (Jn. 3:3). He was referring to the fundamental life change that occurs when a person decides to follow Jesus. An act of faith, it is an act of conversion. It requires an act of God to turn a cold and callous heart of stone into a living, throbbing heart of flesh (Ezek. 36:26). Being born again brings with it new life (Rom. 6:4), new perspective, a desire to follow the straight and narrow path (Matt. 7:14). We may not be convicts who have spent years behind bars, but we all have gone astray and committed sin (Isa. 53:6). We all need to experience this healing, this rebirth that frees us from our own prisons, much like Carlito.

Carlito's reference to being born again takes us back to the first century conversation between Jesus and Nicodemus. Jesus told this Jewish leader, "I tell you the truth, no one can see the kingdom of God unless he is born again" (Jn. 3:3). He was referring to the fundamental life change that occurs when a person decides to follow Jesus. An act of faith, it is an act of conversion. It requires an act of God to turn a cold and callous heart of stone into a living, throbbing heart of flesh (Ezek. 36:26). Being born again brings with it new life (Rom. 6:4), new perspective, a desire to follow the straight and narrow path (Matt. 7:14). We may not be convicts who have spent years behind bars, but we all have gone astray and committed sin (Isa. 53:6). We all need to experience this healing, this rebirth that frees us from our own prisons, much like Carlito. But it is Carlito's lawyer, David Kleinfeld (Sean Penn in a wild afro) who proves more of a threat. Kleinfeld has gotten Carlito out of prison, so Carlito owes him. And he treats him like a dear friend, even a brother. But this lawyer is a sleazy and corrupt cokehead, and has more problems than the ex-con. When he calls on Carlito for a favor, old loyalties prove too strong. Even his old love Gail (Penelope Ann Miller) cannot dissuade him from doing something foolish.

But it is Carlito's lawyer, David Kleinfeld (Sean Penn in a wild afro) who proves more of a threat. Kleinfeld has gotten Carlito out of prison, so Carlito owes him. And he treats him like a dear friend, even a brother. But this lawyer is a sleazy and corrupt cokehead, and has more problems than the ex-con. When he calls on Carlito for a favor, old loyalties prove too strong. Even his old love Gail (Penelope Ann Miller) cannot dissuade him from doing something foolish. Carlito's loyalty to his friend proves his undoing. He knows this, yet still proceeds: "There is a line you cross, you don't never come back from. Point of no return. Dave crossed it. I'm here with him." Just like in

Carlito's loyalty to his friend proves his undoing. He knows this, yet still proceeds: "There is a line you cross, you don't never come back from. Point of no return. Dave crossed it. I'm here with him." Just like in

McAffrey represents newspapers of the past. Writing with pen, publishing in print, he lives for the investigation. He wants to see his stories in hard copy. Reporters produce newsprint. Frye, on the other hand, is the new wave of the journalistic future. She blogs, she produces digital copy. More and more newspapers are finding it difficult to turn a profit. News is migrating to on-line, on all-the-time options. With internet in the pocket of paying customers in the form of smart phones and iPods, why wait for today's news to show up in print as tomorrow's headlines? Why not read all about it now, on the internet? Who can wait 12 hours for their news? This is a now generation.

McAffrey represents newspapers of the past. Writing with pen, publishing in print, he lives for the investigation. He wants to see his stories in hard copy. Reporters produce newsprint. Frye, on the other hand, is the new wave of the journalistic future. She blogs, she produces digital copy. More and more newspapers are finding it difficult to turn a profit. News is migrating to on-line, on all-the-time options. With internet in the pocket of paying customers in the form of smart phones and iPods, why wait for today's news to show up in print as tomorrow's headlines? Why not read all about it now, on the internet? Who can wait 12 hours for their news? This is a now generation. One of the strengths of State of Play is its cast. Russell Crowe, once again looking dumpy and homely as he did in

One of the strengths of State of Play is its cast. Russell Crowe, once again looking dumpy and homely as he did in  There is a history between McAffrey and Collins. They were friends in college but became estranged, as many college room-mates do. In one emotional scene, Collins confronts McAffrey:

There is a history between McAffrey and Collins. They were friends in college but became estranged, as many college room-mates do. In one emotional scene, Collins confronts McAffrey:

Realizing that his family will not give in until he has settled down, Luis hatches a perfect plan to get them off his back. He will get married to a "perfect woman" and then be stood up at the altar. In this way, he can almost get married yet stay single and gain lifelong sympathy from the mother and sisters. Of course, this would not be a comedy if the plan played out perfectly.

Realizing that his family will not give in until he has settled down, Luis hatches a perfect plan to get them off his back. He will get married to a "perfect woman" and then be stood up at the altar. In this way, he can almost get married yet stay single and gain lifelong sympathy from the mother and sisters. Of course, this would not be a comedy if the plan played out perfectly. Different parts of this premise have appeared in earlier films over the years. Richard Gere hired Julia Roberts to be his escort 20 years ago in Pretty Woman. Kate Hudson tried to show How to Lose a Guy in 10 Days. Here these combine as a hiring and firing of a bride. And of course, this focus on my best friend's sister's wedding brings to mind Julia Roberts again in My Best Friend's Wedding.

Different parts of this premise have appeared in earlier films over the years. Richard Gere hired Julia Roberts to be his escort 20 years ago in Pretty Woman. Kate Hudson tried to show How to Lose a Guy in 10 Days. Here these combine as a hiring and firing of a bride. And of course, this focus on my best friend's sister's wedding brings to mind Julia Roberts again in My Best Friend's Wedding.

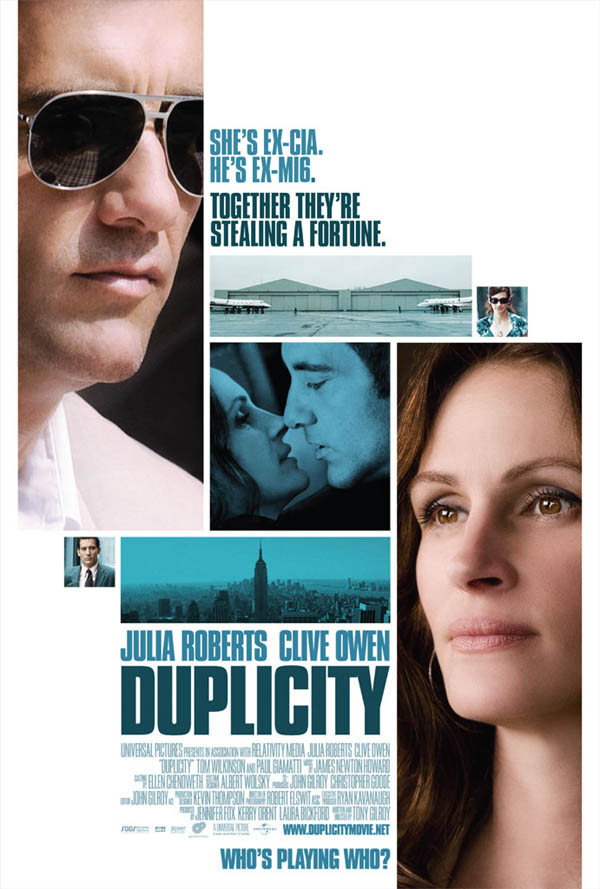

Indeed, the opening scene sets the tone well. Sitting on the tarmac of a small airport are two company jets, from two rival pharmaceutical companies, facing each other. When Richard Garsik (Paul Giamatti, Sideways) sees his arch-nemesis Howard Tully (Tom Wilkinson, Michael Clayton), something snaps. They get into a yelling, shoving, and wrestling match. There is no love lost between these two.

Indeed, the opening scene sets the tone well. Sitting on the tarmac of a small airport are two company jets, from two rival pharmaceutical companies, facing each other. When Richard Garsik (Paul Giamatti, Sideways) sees his arch-nemesis Howard Tully (Tom Wilkinson, Michael Clayton), something snaps. They get into a yelling, shoving, and wrestling match. There is no love lost between these two. True success is measured in healthy balance of work and play; it is measured in healthy relationships, with family and friends, even coworkers. True success is measured in pleasing God (1 Thess. 2:4), obeying him and glorifying him (1 Cor. 10:31). These will bring lasting rewards, crowns that will not fade with time but will endure throughout eternity (1 Pet. 5:4).

True success is measured in healthy balance of work and play; it is measured in healthy relationships, with family and friends, even coworkers. True success is measured in pleasing God (1 Thess. 2:4), obeying him and glorifying him (1 Cor. 10:31). These will bring lasting rewards, crowns that will not fade with time but will endure throughout eternity (1 Pet. 5:4). This brings us to trust and love. Trust is in short supply here. Can spies really trust? Who do they trust? Certainly, Ray and Claire must trust each other if there is true love between them. But is there this love? For us, if we love someone we need to trust enough to let them see who we really are. We keep our true self hidden most of the time in pursuit of success, but the woman we sleep with needs to know her husband. Ray puts his finger on this when he says to Claire, "I look at you, and I think, 'That woman . . . that woman knows who I am and loves me anyway.' " What is necessary in a human love relationship is infinitely more relevant with God.

This brings us to trust and love. Trust is in short supply here. Can spies really trust? Who do they trust? Certainly, Ray and Claire must trust each other if there is true love between them. But is there this love? For us, if we love someone we need to trust enough to let them see who we really are. We keep our true self hidden most of the time in pursuit of success, but the woman we sleep with needs to know her husband. Ray puts his finger on this when he says to Claire, "I look at you, and I think, 'That woman . . . that woman knows who I am and loves me anyway.' " What is necessary in a human love relationship is infinitely more relevant with God.

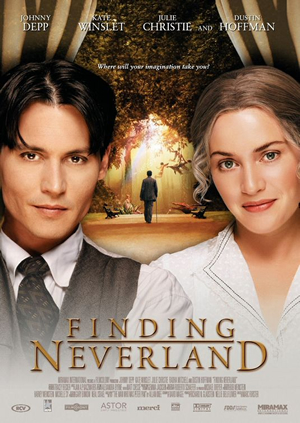

Enter Sylvia Llewelyn Davies (Kate Winslet) and her brood of kids. When Barrie is walking his dog in a London park, he meets Peter (Freddie Highmore), one of her sons. Peter and Barrie are foils to one another, at the very heart of the film. When Barrie invites Sylvia and her sons to sit and watch him put on a show, he entreats them to activate their childlike imaginations and turn his dog, Porthos, into a dancing bear. The initial interchange between Peter and Barrie set the tone for the film and defines a key theme.

Enter Sylvia Llewelyn Davies (Kate Winslet) and her brood of kids. When Barrie is walking his dog in a London park, he meets Peter (Freddie Highmore), one of her sons. Peter and Barrie are foils to one another, at the very heart of the film. When Barrie invites Sylvia and her sons to sit and watch him put on a show, he entreats them to activate their childlike imaginations and turn his dog, Porthos, into a dancing bear. The initial interchange between Peter and Barrie set the tone for the film and defines a key theme. The whole concept of believing is highlighted in two other scenes. First, we see Barrie trying to show the boys how to fly a kite. When Michael, the youngest, tries the first time he fails and the other boys offer dream-quashing comments, "Oh, I told you this wasn't going to work!" and "I don't think he's fast enough." But the child-like Barrie speaks words of encouragement, calling for faith, "It's not going to work if no one believes in him!" Faith is what they needed.

The whole concept of believing is highlighted in two other scenes. First, we see Barrie trying to show the boys how to fly a kite. When Michael, the youngest, tries the first time he fails and the other boys offer dream-quashing comments, "Oh, I told you this wasn't going to work!" and "I don't think he's fast enough." But the child-like Barrie speaks words of encouragement, calling for faith, "It's not going to work if no one believes in him!" Faith is what they needed. Barrie's playing with the boys releases his own imagination. And from this emerges the ground-breaking concept of a playful play. At the time, plays were serious, not fantastic. But, drawing heavily from his times with the Llewelyn Davis family, he creates "Peter Pan," the story of a boy who would not grow up, and who goes to Neverland, the mythical place where we never grow old. And this would be his magnum opus.

Barrie's playing with the boys releases his own imagination. And from this emerges the ground-breaking concept of a playful play. At the time, plays were serious, not fantastic. But, drawing heavily from his times with the Llewelyn Davis family, he creates "Peter Pan," the story of a boy who would not grow up, and who goes to Neverland, the mythical place where we never grow old. And this would be his magnum opus.