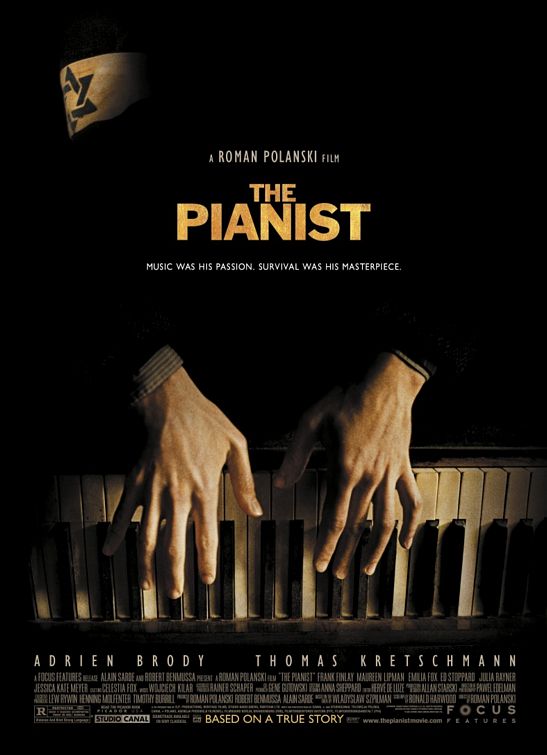

Director: Roman Polanski, 2002.

In 2002, drawing from his own experiences as a boy in war-torn Poland, Polanski (Chinatown) hit the high-point of his career. He took the memoirs of Wladyslaw Szpilman and with Ron Harwood's screenplay adaptation, created this masterpiece. Much of the credit goes to Adrien Brody, the British actor who totally poured himself into a role tailor-made for him. All three won Academy Awards for The Pianist. But despite Polanski's Oscar for Best Director, the film itself lost the big prize (Best Picture) to Chicago, which was a travesty of justice.

Szpilman (Brody) was Poland's most accomplished pianist before World War 2. As the movie starts we see him in a radio studio beautifully playing the piano. But then the tanks start shooting, the bombs start falling, and the studio is damaged. He can no longer avoid the rapidly escalating situation. Germany is invading his homeland. His time as a concert pianist and radio performer has come to a sudden end.

When he returns to his home, where he lives with his siblings and his parents (Frank Finlay and Maureen Lipman), we realize he is a Jew. The first half of The Pianist focuses on the impact on their lives of this German invasion.

At first nothing changes. But then little by little, there is a progressive dehumanization of the Jewish people. It starts with the ban of Jews in cafes, restaurants and parks. It moves to their "branding," like cattle, as they are required to wear the star of David. It culminates in their forced eviction and resettlement in the Warsaw ghetto, an area that is literally walled in with bricks. It concludes with the deportation to the concentration camps where they are mercilessly exterminated like vermin. This is a harrowing descent into hell.

Craig Detweiler, in his book "Into the Dark," analyses The Pianist as one of the most influential movies of the last decade. He highlights the questions that this film raises: "How much evil are we capable of? How much can we tolerate? How do we muster the courage to continue in the face of wartime atrocities?" Without specifically answering these rhetorical questions, he points out that the movie puts "audiences through the wringer as a wake-up call. Elie Wiesel describes this important work of remembering: 'The memory of death will serve as a shield against death.' [This] powerful film offers impassioned and personal cries of 'Never Again!' "

One of the intents of The Pianist, then, is to act as a reminder and a deterrent to the horrors of the Holocaust. Certainly Polanski paints a grim and colorless portrait of a dark reality. He imbues the film with a pervading sense of desperation. Yet, in focusing on one man throughout he makes this catastrophe very personal. In watching Szpilman wither and wane, we see the riveting impact of the dehumanization. We don't need to see the atrocities of the Holocaust inside the concentration camps; other movies (Schindler's List and recently The Boy in the Striped Pajamas) have done this. It is enough to view the deterioration of life in the ghetto.

As his life is forced into the overcrowded and underfed conditions in the Warsaw Ghetto, survival becomes paramount. At first he wants to be active in the underground distributing propaganda, but he is told, "You're too well known, Wladek. And you know what? You musicians don't make good conspirators. You're too . . . too . . . musical!" His very essence, his life passion, prevents him from becoming part of the resistance. He can only look on as he plays piano as entertainment in one of the last remaining restaurants for Jews.

As his life is forced into the overcrowded and underfed conditions in the Warsaw Ghetto, survival becomes paramount. At first he wants to be active in the underground distributing propaganda, but he is told, "You're too well known, Wladek. And you know what? You musicians don't make good conspirators. You're too . . . too . . . musical!" His very essence, his life passion, prevents him from becoming part of the resistance. He can only look on as he plays piano as entertainment in one of the last remaining restaurants for Jews.But music and survival go hand in hand for Szpilman. Without music he cannot exist. When his family is being herded, with the rest of these Jews, like cattle into cattle cars for transportation out of the ghetto, Szpilman's life is saved. He remains as one of the conscripted forced laborers. And when this becomes unbearable, he escapes into Warsaw proper. With some help from friends, he flees from apartment to apartment, living locked in like a caged animal in a zoo.

Polanski's use of Chopin throughout the film as the background score is moving and effective. The Polish composer's evoctive music brings a sad mood, yet frosted with a subtle hint of hope. Detweiler comments on a powerful moment: "The scene in which Szpilman discovers an upright piano in his latest safe house affirms the sustaining power of art. Szpilman's private recital drives all the horrors of his reality away."

Polanski's use of Chopin throughout the film as the background score is moving and effective. The Polish composer's evoctive music brings a sad mood, yet frosted with a subtle hint of hope. Detweiler comments on a powerful moment: "The scene in which Szpilman discovers an upright piano in his latest safe house affirms the sustaining power of art. Szpilman's private recital drives all the horrors of his reality away."Survival is a major theme in The Pianist. To survive these horrors, Szpilman had to retreat from the harshness surrounding him and use his gifts, his passions and his memories to give himself strength and purpose. Human beings react differently in this kind of situation. Some will give up, become fatalistic and die. Many did. Others will rally and find a strong sense of self-preservation, often surviving at the expense of others. Szpilman, once separated from his family, focused on personal survival mostly alone. Yet, God-fearers and Jesus-followers will find that God never leaves them or fails them (Heb. 13:5-6). He is only a prayer away.

Another major theme is the arbitrariness of life and death. Its randomness is illustrated in two ghetto scenes. In one, a group of Nazis enter an apartment just when a Jewish family is sitting down to dinner. When all but one family member stands up, they pour their wrath on the one still sitting. They pick up this wheel-chair-bound man and toss him over the balcony to fall to his death. In another scene, a Nazi officer pulls men from the conscript work force as they are on their way back to the ghetto after the day's work. Ordering these selected men to lie down, he calmly shoots each one in the head. Abritrary and ruthless.

Toward the end, this arbitrariness directly encounters Szpilman. When he is discovered living in a bombed-out building by a German officer, Captain Wilm Hosenfeld (Thomas Kretschmann, Valkyrie, Transsiberian) he is asked what he does. When he says he is a pianist, he is led to a grand piano, amazingly intact, and ordered to play. The man who lived to play, now must play to live. Thinking his life is over, he plays a passionate and haunting movement that transports him to his earlier days while captivating the German.

Toward the end, this arbitrariness directly encounters Szpilman. When he is discovered living in a bombed-out building by a German officer, Captain Wilm Hosenfeld (Thomas Kretschmann, Valkyrie, Transsiberian) he is asked what he does. When he says he is a pianist, he is led to a grand piano, amazingly intact, and ordered to play. The man who lived to play, now must play to live. Thinking his life is over, he plays a passionate and haunting movement that transports him to his earlier days while captivating the German.In these events, we are asked to consider if life is random. How can some live while others die? There is no difference in those who remain, except they happened to be in the right place in the line. Is there really a God who providentially moves in his creation? When Szpilman asks Hosenfeld how he can thank him, he is answered, "Thank God, not me. He wants us to survive. Well, that's what we have to believe." Polanski leaves us with an ambiguous answer. But followers of Jesus understand that we do have to believe this. He is in control (Acts 17:24-26), even in the midst of the Holocaust. He does love us (Jn. 3:16). He does want us to survive. The problem of evil is an age old problem, and not one to be solved in a simple blog posting or enduring movie. Yet, these scenes make us realize that we are all but a hair-breadth away from death, and it is only by the grace of God that we go on living. It is thanks to God that we breathe our next breath (Acts 17:28).

Detweiler leaves us with an appropriate closing thought:

The grace extended by a Nazi officer suggests that individuals can still make aCopyright ©2009, Martin Baggs

difference even amid the most trying circumstances. Even within genocide, people

can demonstrate redemptive qualities. Good people can wear bad uniforms. The

universe may appear capricious; God may seem absent. But we stil retain a choice

in how we respond -- offering a coat of comfort or a cold shoulder of death.

History asks us to choose wisely.

No comments:

Post a Comment