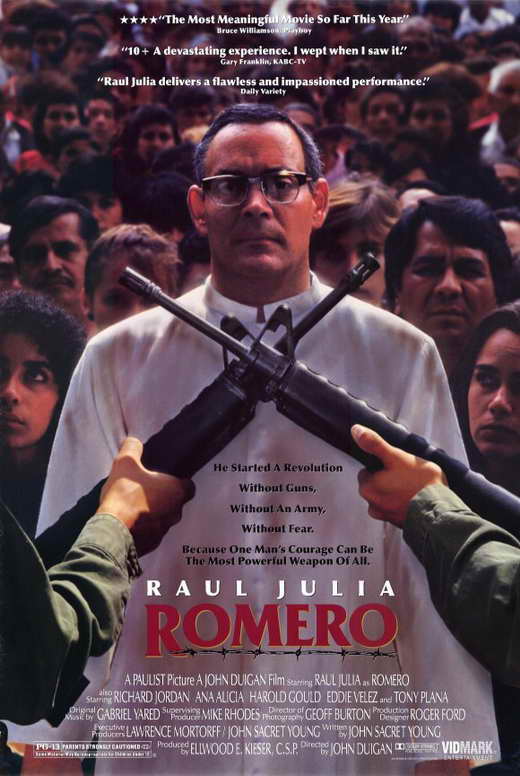

Director: John Duigan, 1989 (PG-13)

Romero presents a true biography of man who wanted to live in the cloisters but who was forced to live in the crosshairs. Produced by the Paulist Fathers, a Roman Catholic order of teachers, it paints the picture of internal transformation, focusing on the message of social justice not political revolution. Despite a known ending, in an assassination on March 24, 1980, the film still presents a compelling character drama and a challenge to Christian viewers.

Set in El Salvadore in the late 70s, the film immediately sets the scene. The country is led by a government that is repressing the common people, while communist revolutionaries fight a guerilla war against the military. The peasants are caught in the middle and no one seems to care. We meet Bishop Oscar Romero (Raul Julia) talking to another priest, one more active and vocal. This priest appeals to Romero: “Jesus is not somewhere up in the clouds lying in a hammock. Jesus is down here with us, building a kingdom, Oscar, what else can I do? I cannot love God whom I do not see if I do not love my brothers and sisters, whom I can see.” But Romero suggests he might be considered a subversive.

This brings to mind the exact sentiment the apostle John declared in his first epistle: “Whoever claims to love God yet hates a brother or sister is a liar. For whoever does not love their brother and sister, whom they have seen, cannot love God, whom they have not seen” (1 Jn. 4:20). We will not see God in this present life, but we will see his children who live all around us. How we treat them, as Jesus pointed out, indicates how we would treat him (Matt. 25:31-46). In being called to love God, we are also being called to love people. That becomes our yardstick.

In this first interaction and its subsequent scenes, we see Romero as a man who leans towards the government, who is more comfortable with his books than with his congregants. Apolitical, Romero wants to be left alone. So when the archbishop dies and must be replaced, Rome selects Romero become archbishop as “a good compromise choice”, as one observer points out. His uncontroversial manner and desire to avoid rocking the boat, would make him a perfect choice, both for the distant Roman Church and the oppressive government.

His

archbishopric inauguration shows him quietly receiving numerous gifts from the

upper classes and the government. And then a subsequent reception contrasts

starkly with an out-door mass held by one of his priestly friends. While

well-decked out guests swill champagne, poor peasants take mass. But a

government death squad shows up to take action against this gathering,

resulting in bodies in the street and blood in the gutters. This juxtaposition of

scenes communicates the disparity in class and highlights Romero’s initial

position.

His

archbishopric inauguration shows him quietly receiving numerous gifts from the

upper classes and the government. And then a subsequent reception contrasts

starkly with an out-door mass held by one of his priestly friends. While

well-decked out guests swill champagne, poor peasants take mass. But a

government death squad shows up to take action against this gathering,

resulting in bodies in the street and blood in the gutters. This juxtaposition of

scenes communicates the disparity in class and highlights Romero’s initial

position.As the film progresses, Romero experiences the effects of the government’s authoritarianism in death of priests and others, and slowly his views change. Though still a somewhat introspective man, he begins to pull away from his earlier position and becomes more radicalized. In the middle of the movie, the social justice theme emerges: “The mission of the church is to identify itself with the poor, and to join with them in their struggle for justice.

The bible underscores this them of social justice any number of times. The psalmist declared, “I know that the Lord secures justice for the poor and upholds the cause of the needy” (Psa. 140:12). The prophet Isaiah said, “with righteousness he will judge the needy, with justice he will give decisions for the poor of the earth” (Isa. 11:4). If God’s heart lies with the poor and the oppressed, so too must that of the church. We must align ourselves with the victims of such oppression and injustice. When society ignores them, we must embrace them. Jesus did this for the marginalized, and so must we in the church.

The

heart of the film is this gradual transformation, from complacency to

commitment. Raul Julia gives a controlled performance that powerfully portrays

this change from bookish to brave until he ends up a leader that the people

will follow. Through his rhetoric from the pulpit he challenges the enemies of

the church and calls to Christ’s followers to live as he has called us to do.

The

heart of the film is this gradual transformation, from complacency to

commitment. Raul Julia gives a controlled performance that powerfully portrays

this change from bookish to brave until he ends up a leader that the people

will follow. Through his rhetoric from the pulpit he challenges the enemies of

the church and calls to Christ’s followers to live as he has called us to do.Indeed, by the final act Romero’s “conversion” is complete. His voice emerges, as evidenced in a radio address he quietly yet passionately gives:

I am a shepherd, who with his people has begun to learn a beautiful and difficult truth. Our faith requires that we immerse ourselves in the world. I believe economic injustice is the root cause of our problems. From it stems all the violence. The church has to be incarnated in those who fight for freedom, and defend them, and share in their persecution.Although economic injustice may not be the root of all problems, it certainly contributes to the problems in many regions. Romero offers a real solution. The church has a role. As God incarnated himself into history in Jesus Christ to solve our sin problem, we must incarnate ourselves in situations where social injustice prevails and play our part.

Steven Greydanus, in his review of the film, offers a fitting conclusion:

Archbishop Romero was killed in the very act of offering the sacrifice of the Mass, almost in the act of elevating the Eucharistic elements. Simply by portraying this event essentially as it happened, Romero presents the archbishop’s life and death as a sacrifice in union with the sacrifice of Christ.

This final sacrifice is foreshadowed by other Masses offered under threatening or difficult circumstances. The Mass, we see, is a bold and radical act, even in a way a revolutionary act: for in the Mass Jesus is with us and in us. The Mass is the fullest earthly expression of that divine solidarity with which the Lord himself challenged one of the church’s earliest oppressors: "Why are you persecuting me?"

It’s a question that continues to apply to all who persecute God’s children anywhere in the world.”Copyright ©2013, Martin Baggs

No comments:

Post a Comment