Director Lasse Hallström, 2000.

"Once upon a time, there was a quiet little village in the French countryside, whose people believed in Tranquilité - Tranquility. If you lived in this village, you understood what was expected of you. You knew your place in the scheme of things." Thus begins Chocolat. Set in 1959, tradition, expectations, appearances, all are an integral part of life in this charming, sleepy town. All will be challenged and changed by the end of the movie.

Against a backdrop of the beautiful landscape, two people in red capes scurry, backs bent against the wind that seems to push them forward to their destination. When they a

rrive, they set up shop, literally, in an empty patisserie. Single mother Vianne (Juliette Binoche) with her young daughter open not a pastry shop, but a chocolaterie, a store where she makes magical confections from Mayan recipes.

rrive, they set up shop, literally, in an empty patisserie. Single mother Vianne (Juliette Binoche) with her young daughter open not a pastry shop, but a chocolaterie, a store where she makes magical confections from Mayan recipes.Her arrival, however, is in the middle of Lent, where abstinence is rewarded and indulgence is frowned upon. Mayor Comte Reynaud (Alfred Molina) draws the battle lines early. He will not countenance his villagers frequenting her store. Yet, as those in real relational need drop by, Vianne works a magic, mostly by listening and befriending. Her warmth is natural and she genuinely seems to care -- about people not appearances.

Just when things seem to have hit rock bottom, a group of river rats, floating gypsy-like travelers, arrive. Of course the townsfolk want nothing to do with them, but Vianne offers acceptance and tolerance. She is ready to welcome them. Perhaps being an outsider, she is drawn to them. Perhaps it is Roux, the handsome Johnny Depp, who is attracted to her, and she to him.

Just when things seem to have hit rock bottom, a group of river rats, floating gypsy-like travelers, arrive. Of course the townsfolk want nothing to do with them, but Vianne offers acceptance and tolerance. She is ready to welcome them. Perhaps being an outsider, she is drawn to them. Perhaps it is Roux, the handsome Johnny Depp, who is attracted to her, and she to him.As in other movies (An Unfinished Life, The Cider House Rules), Hallström explores facets of humanity with a character-driven story. Here he creates a warm-hearted tale that examines love, tolerance and acceptance. Against a backdrop of the simple pleasure of chocolate, indeed using chocolate as a metaphor, he contrasts religion and law with freedom and grace.

As Molina and the church are a metaphor for religion and rigid morality, so Vianne and chocolate are a metaphor for relationships and freedom. The church here is all about appearance, externals. Sensual indulgence, eating chocolate, is forbidden; sensual repression is the norm. As one character says, "Don't worry so much about not supposed to." Too much time is wasted in rule-keeping.

When Vianne helps Josephine escape an abusive marriage, and points out the wounds to the mayor, he responds, "Your husband will be made to repent for this." That is what the town and the church is all about. Repentance for them is forced, and is more for the church than for the individual. Repentance, true repentance can never be forced. It is inward, a turning away from sin. Only by a contrite heart and willing spirit can a person repent. A person can never be made to repent.

The rigid morality of the mayor is offended by the presence of a single, never-married mother. The contrast is flexible immorality, and this is on display in the immediate attraction and sexual indulgence of Vianna with Roux. This is wrong biblically, yet the film rises above this to present a deeper message of acceptance.

Vianne has a knack for going below the surface, for drawing people out to find their pain and deal with it. As she gets to know her landlady, Voizin (Judi Dench), she enables Voizin to see her grandson again. Where the rigid sensibilities of the townsfolk have driven relatives apart, Vianne's love heals their wounds and brings them back together.

The beauty of Chocolat is due in large part to the accomplished cast. Binoche, an Oscar-winner for The English Patient, is cast to perfection here, and offers a role that recalls her brilliance in Kieslowski's Blue (rather than her by-the-numbers role in the 2007 Dan in Real Life). Her warmth and charm exude and she has wonderful chemistry with Depp, here using an Irish accent. Molina is believable as a buttoned-down, stodgy moralist, who is the puppet-master behind the young Catholic priest. Dench is gruff and real as an old woman estranged from her daughter, played by Carrie-Ann Moss (Trinity in The Matrix).

The beauty of Chocolat is due in large part to the accomplished cast. Binoche, an Oscar-winner for The English Patient, is cast to perfection here, and offers a role that recalls her brilliance in Kieslowski's Blue (rather than her by-the-numbers role in the 2007 Dan in Real Life). Her warmth and charm exude and she has wonderful chemistry with Depp, here using an Irish accent. Molina is believable as a buttoned-down, stodgy moralist, who is the puppet-master behind the young Catholic priest. Dench is gruff and real as an old woman estranged from her daughter, played by Carrie-Ann Moss (Trinity in The Matrix).In a telling scene near the end, Père Henri, the young parish priest, finally frees himself from the repressive restriction of the mayor to preach his own sermon, not one handed to him. Rarely do we find a movie using a pastor's sermon to deliver its own message. Yet this is what Hallström does. And he does so effectively:

Do I want to speak of the miracle of our Lord's divine transformation? Not really, no. I don't want to talk about his divinity. I'd rather talk about his humanity. I mean, you know, how he lived his life, here on Earth. His kindness, his tolerance... Listen, here's what I think. I think that we

can't go around... measuring our goodness by what we don't do. By what we deny ourselves, what we resist, and who we exclude. I think... we've got to measure goodness by what we embrace, what we create... and who we include.

So Chocolat is really a movie about incusivism vs exclusivism. And a beautiful and moving film it is. Though there are some questionable moments, and it veers towards too clear a black/white delineation (evil conservatism vs good liberalism), it is a reminder that life is better when shared. It is better when we enjoy it, when we include others, when we tear up our rules and our lists of "shoulds" and throw away our masks. It is time to embrace others who are different from us. It is time to do the things we can do. It is time to love, laugh, and liberate . . . ourselves and others!

Copyright ©2008, Martin Baggs

The historical storyline has Tomas, a Spanish conquistador sent on a quest by his beloved Queen Isabella to find the tree of life that brings immortality. This tree is in a Mayan temple in South America, and promises eternal life. Whether this is history or fictional fantasy from the present is unclear.

The historical storyline has Tomas, a Spanish conquistador sent on a quest by his beloved Queen Isabella to find the tree of life that brings immortality. This tree is in a Mayan temple in South America, and promises eternal life. Whether this is history or fictional fantasy from the present is unclear. The present shows Tom Creo, a workaholic scientist trying to find the cure for brain cancer by experimenting with new drugs and treatments. His wife, Izzi, is dying of this disease and Tom feels the weight of impending loss as an anchor dragging him down to the abyss. His quest is to save his wife.

The present shows Tom Creo, a workaholic scientist trying to find the cure for brain cancer by experimenting with new drugs and treatments. His wife, Izzi, is dying of this disease and Tom feels the weight of impending loss as an anchor dragging him down to the abyss. His quest is to save his wife. Through all three stories, director Aronofsky uses light to communicate awe and hope. Just as

Through all three stories, director Aronofsky uses light to communicate awe and hope. Just as  All three intersecting stories deal with the concept of life and death. In particular, the spotlight is on eternal life, with the shadow of death being ever-present. The innate desire for eternal life is clear in all three stories. The initial biblical reference to eating from the "tree of life" (Gen. 3:22-24) forms the metaphorical center to the film. If Tomas/Tom can find the tree and eat from it, he can live eternally. He can save his queen. And he can save his dying wife.

All three intersecting stories deal with the concept of life and death. In particular, the spotlight is on eternal life, with the shadow of death being ever-present. The innate desire for eternal life is clear in all three stories. The initial biblical reference to eating from the "tree of life" (Gen. 3:22-24) forms the metaphorical center to the film. If Tomas/Tom can find the tree and eat from it, he can live eternally. He can save his queen. And he can save his dying wife.

After the wedding, the three and two other buddies, including Stan (John Cazale), go into the mountains to hunt deer. This is where we see Michael as the leader of this group. These are regular guys, who joke, swear, and do stupid guy things.

After the wedding, the three and two other buddies, including Stan (John Cazale), go into the mountains to hunt deer. This is where we see Michael as the leader of this group. These are regular guys, who joke, swear, and do stupid guy things.

In The Deer Hunter we see three different effects. On Michael, he becomes stronger and tougher on the outside, yet is distanced from those he knows and loves. His change is not apparent at first, but is there nonetheless. Steven is changed physically and emotionally. He cannot bear to be seen as he is now, and withdraws physically to protect his fragile ego. Nick, on the other hand, withdraws mentally and emotionally. He is a shell, who no longer cares for his own physical life. Together, these three provide a spectrum of the effects of war.

In The Deer Hunter we see three different effects. On Michael, he becomes stronger and tougher on the outside, yet is distanced from those he knows and loves. His change is not apparent at first, but is there nonetheless. Steven is changed physically and emotionally. He cannot bear to be seen as he is now, and withdraws physically to protect his fragile ego. Nick, on the other hand, withdraws mentally and emotionally. He is a shell, who no longer cares for his own physical life. Together, these three provide a spectrum of the effects of war.

Director Mike Newel (Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, Four Weddings and a Funeral) clearly portrays the reality of love at first sight in Florentino's experience. Further, he compares love-sickness with cholera, an epidemic prevalent at the time. As the disease claims so many in the city, the young Florentino appears to be a victim himself. But it is only his love-sickness, as he waits for the young Fermina to reply to his love letters. Love has taken such a hold that it affects his health. Both love and cholera lead here to physical distress.

Director Mike Newel (Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, Four Weddings and a Funeral) clearly portrays the reality of love at first sight in Florentino's experience. Further, he compares love-sickness with cholera, an epidemic prevalent at the time. As the disease claims so many in the city, the young Florentino appears to be a victim himself. But it is only his love-sickness, as he waits for the young Fermina to reply to his love letters. Love has taken such a hold that it affects his health. Both love and cholera lead here to physical distress. Cholera plays a key role in the film's development. When Fermina herself appears to have the disease, her father meets Dr Urbino (Benjamin Bratt). Urbano is the urbane and educated man he has been wanting his daughter to marry and she does. Over time, they have a family and grow old together.

Cholera plays a key role in the film's development. When Fermina herself appears to have the disease, her father meets Dr Urbino (Benjamin Bratt). Urbano is the urbane and educated man he has been wanting his daughter to marry and she does. Over time, they have a family and grow old together. Love in the Time of Cholera offers some thoughts on aging and love, a partnership that is often downplayed in our youth-focused culture. "I discovered to my joy, that it is love and not death that has no limits," says Florentino. Even at the end of his life, his love for Giovanna burns fiercely. In a monologue that unwittingly overflows with religious significance, he says, "Age has no reality except in the physical world. The essence of a human being is resistant to the passage of time. Our inner lives are eternal, which is to say that our spirits remain as youthful and vigorous as when we were in full bloom. Think of love as a state of grace, not the means to anything, but the alpha and omega. An end in itself." Age does not prevent him from loving the love of his youth. Love, indeed, has no limits. Love, in fact, transposes time. Whatever our physical age, we can experience eternal love, a love from the Father (John 3:16), and we can express love as we have known it from our youth.

Love in the Time of Cholera offers some thoughts on aging and love, a partnership that is often downplayed in our youth-focused culture. "I discovered to my joy, that it is love and not death that has no limits," says Florentino. Even at the end of his life, his love for Giovanna burns fiercely. In a monologue that unwittingly overflows with religious significance, he says, "Age has no reality except in the physical world. The essence of a human being is resistant to the passage of time. Our inner lives are eternal, which is to say that our spirits remain as youthful and vigorous as when we were in full bloom. Think of love as a state of grace, not the means to anything, but the alpha and omega. An end in itself." Age does not prevent him from loving the love of his youth. Love, indeed, has no limits. Love, in fact, transposes time. Whatever our physical age, we can experience eternal love, a love from the Father (John 3:16), and we can express love as we have known it from our youth.

When we first see Dunne, at the start of Half Nelson, he is leaning on walls or mostly hiding behind walls in the school. And he wears huge sunglasses. He has something to hide. That something is his addiction.

When we first see Dunne, at the start of Half Nelson, he is leaning on walls or mostly hiding behind walls in the school. And he wears huge sunglasses. He has something to hide. That something is his addiction. oor, semi-incapacitated, his secret is out in the open. But Drey is also a lonely soul, being raised by an overworked single mother who is barely home because of her job. This shared secret leads to the beginnings of a friendship.

oor, semi-incapacitated, his secret is out in the open. But Drey is also a lonely soul, being raised by an overworked single mother who is barely home because of her job. This shared secret leads to the beginnings of a friendship. As Dunne lectures his students, he is unknowingly sharing a window into his soul. "Change moves in spirals, not circles. . . We're always changing. And it's important to know that there are some changes you can't control and that there are others you can." He is changing, and it is a spiral but a downward spiral. Like many addicts, he fools himself into thinking he is control: "For the most part, I do it now to get by, but I can handle it." Drugs are a crutch for him, a weak crutch. They are not supporting but bringing him further and further down toward the abyss.

As Dunne lectures his students, he is unknowingly sharing a window into his soul. "Change moves in spirals, not circles. . . We're always changing. And it's important to know that there are some changes you can't control and that there are others you can." He is changing, and it is a spiral but a downward spiral. Like many addicts, he fools himself into thinking he is control: "For the most part, I do it now to get by, but I can handle it." Drugs are a crutch for him, a weak crutch. They are not supporting but bringing him further and further down toward the abyss. Half Nelson shows the destructiveness and deceitfulness of addictions. Once they have their hooks in you, they rarely let go. Like a wrestler locking you in a half-nelson, it is tough to escape. There are many types of addiction, but they all have this in common. Even when we think we are in control, when we think we have it licked, we are often deceiving ourselves. What may have started as a crutch, a way to handle the pain of life, takes over.

Half Nelson shows the destructiveness and deceitfulness of addictions. Once they have their hooks in you, they rarely let go. Like a wrestler locking you in a half-nelson, it is tough to escape. There are many types of addiction, but they all have this in common. Even when we think we are in control, when we think we have it licked, we are often deceiving ourselves. What may have started as a crutch, a way to handle the pain of life, takes over.

With the help of Gerben Kuipers, a key figure in the Dutch resistance, Rachel becomes Ellis de Vries, a worker in the underground movement, seeking vengeance for her family's murder. On a mission, she meets SS officer Ludwig Muntze (Sebastian Koch, from The Lives of Others), who is obviously attracted to her. When Kuipers son is arrested by the SS, this attraction proves to be opportunistic. What will Ellis do for the resistance effort? Will she seduce an enemy? Will she become one of them to fight against them.

With the help of Gerben Kuipers, a key figure in the Dutch resistance, Rachel becomes Ellis de Vries, a worker in the underground movement, seeking vengeance for her family's murder. On a mission, she meets SS officer Ludwig Muntze (Sebastian Koch, from The Lives of Others), who is obviously attracted to her. When Kuipers son is arrested by the SS, this attraction proves to be opportunistic. What will Ellis do for the resistance effort? Will she seduce an enemy? Will she become one of them to fight against them. As Black Book develops, not only does Muntze discover her duplicity, but he keeps it secret. Both have lost too much to the war, and as two lost-souls they find their humanity superseding their nationality. Love moves them, even changes them, where vengeance cannot.

As Black Book develops, not only does Muntze discover her duplicity, but he keeps it secret. Both have lost too much to the war, and as two lost-souls they find their humanity superseding their nationality. Love moves them, even changes them, where vengeance cannot.

With the school board determined to honor their dead by disbanding the program, the students rally together to persuade them to let it continue. But who will be their coach? President Dedmon (David Strathairn) leads the search. After all prospective candidates turn him down, Jack Lengyel (Matthew McConaughey) calls and applies for the job. A charming father of three, he wins the head coaching position. But that is the only beginning of his obstacles.

With the school board determined to honor their dead by disbanding the program, the students rally together to persuade them to let it continue. But who will be their coach? President Dedmon (David Strathairn) leads the search. After all prospective candidates turn him down, Jack Lengyel (Matthew McConaughey) calls and applies for the job. A charming father of three, he wins the head coaching position. But that is the only beginning of his obstacles. With no team, recruiting is tough indeed. But Jack's optimism and hopeful attitude is contagious. He persuades assistant coach Red Dawson (Matthew Fox, seen recently in

With no team, recruiting is tough indeed. But Jack's optimism and hopeful attitude is contagious. He persuades assistant coach Red Dawson (Matthew Fox, seen recently in

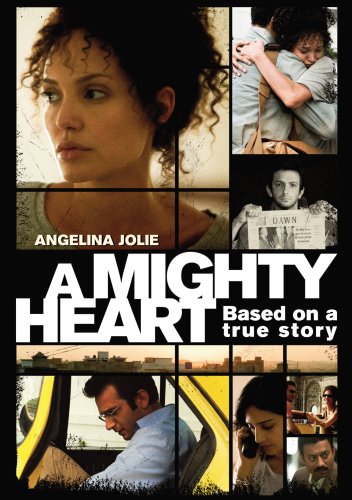

Pregnant Mariane begins the unfathomable inner journey of waiting. Never giving up hope, with the help of US officials, Pakistani police, and her friend Asra (Archie Panjabi, the older sister in Bend it Like Beckham, and the love interest in the new terrorist movie Traitor), she seeks to understand why he is kidnapped and how he can be rescued.

Pregnant Mariane begins the unfathomable inner journey of waiting. Never giving up hope, with the help of US officials, Pakistani police, and her friend Asra (Archie Panjabi, the older sister in Bend it Like Beckham, and the love interest in the new terrorist movie Traitor), she seeks to understand why he is kidnapped and how he can be rescued. Though the movie has a melancholic plot narrative, Jolie portrays a woman with a sense of hope and a strong heart. Is the "mighty heart" of the title a reference to Danny, as a courageous journalist who sought the truth and never lied in his articles, or his wife, who faced up to circumstances with inner fortitude? The book written by Mariane refers to her husband's courage. But perhaps here it is a nuanced reference to both husband and wife. Regardless, Jolie displays a level of acting not seen since she won an Oscar for her role in Girl Interrupted. And this carries the film.

Though the movie has a melancholic plot narrative, Jolie portrays a woman with a sense of hope and a strong heart. Is the "mighty heart" of the title a reference to Danny, as a courageous journalist who sought the truth and never lied in his articles, or his wife, who faced up to circumstances with inner fortitude? The book written by Mariane refers to her husband's courage. But perhaps here it is a nuanced reference to both husband and wife. Regardless, Jolie displays a level of acting not seen since she won an Oscar for her role in Girl Interrupted. And this carries the film. Why was Daniel Pearl kidnapped and subsequently murdered? The movie does not answer these questions. Although it is first reported that he was a spy, this is rescinded. Was it because of his Jewish faith? Or was he simply in the wrong place at the wrong time? He went seeking truth from a terrorist and was willing to put his life on the line as a journalist to bring this truth to the public. A Mighty Heart is as much as message of remembrance as it as a call to recognize the dangers that journalists face in going to war-torn and third-world countries.

Why was Daniel Pearl kidnapped and subsequently murdered? The movie does not answer these questions. Although it is first reported that he was a spy, this is rescinded. Was it because of his Jewish faith? Or was he simply in the wrong place at the wrong time? He went seeking truth from a terrorist and was willing to put his life on the line as a journalist to bring this truth to the public. A Mighty Heart is as much as message of remembrance as it as a call to recognize the dangers that journalists face in going to war-torn and third-world countries.