Director: Michael Radford, 1994.

The ancient Greek poet Euripides once said, "The tongue is mightier than the blade." In the 19th century Edward Bulwer-Lytton recoined this phrase as "The pen is mightier than the sword." In The Postman, Radford brings to center stage the power of words in the form of poetry to sculpt a romance and win a woman's heart.

Writer Massimo Troisi stars as Mario Ruoppolo, a nondescript unemployed fisherman's son who detests fishing. Living on a remote Italian island in 1952, there is little work to be had. But when Pablo Neruda (Philippe Noiret) comes to the island in exile from his native Chile, a part-time postman is needed to carry the copious quantity of fan-mail, mostly from females, to his hilltop villa. Mario gets the job and begins the daily bike-ride to deliver the mail to his one customer.

The film is loosely based on Neruda's actual stay in a villa on the island of Capri in 1952. Neruda was a lifelong communist and poet. Widely considered one of the greatest and most influential poets of the 20th century, he wrote poems in a variety of styles including love and romance. In 1971 he won the Nobel Prize for Literature.

The Postman focuses on the growing friendship between Mario and Neruda. As they grow closer Neruda helps Mario to appreciate poetry and discover metaphor by seeing things around him in his wonderful island enviroment.

The Postman focuses on the growing friendship between Mario and Neruda. As they grow closer Neruda helps Mario to appreciate poetry and discover metaphor by seeing things around him in his wonderful island enviroment.When Mario sees the beautiful Beatrice Russo (Maria Grazia Cucinotta) his heart is captured but his tongue is tied. The shy postman cannot say more than 5 words to her though he wants to woo her. Calling on his friend Neruda, he learns the power of poetry to win her heart. Despite an unexpected and somewhat anticlimactic conclusion, the film is a lyrical ode to love.

Troisi brings an underplayed sense of the everyman to this role. Tall, thin and unprepossessing he is a quiet hero who many in the audience can relate to. No Brad Pitt, he is a leaner John Cusack. The true-life tragedy of The Postman is that Troisi had a known heart condition requiring surgery. But he postponed this so he could finish the film and then the very day after completing the movie he died of a fatal heart attack. This film lives on as his legacy.

Troisi brings an underplayed sense of the everyman to this role. Tall, thin and unprepossessing he is a quiet hero who many in the audience can relate to. No Brad Pitt, he is a leaner John Cusack. The true-life tragedy of The Postman is that Troisi had a known heart condition requiring surgery. But he postponed this so he could finish the film and then the very day after completing the movie he died of a fatal heart attack. This film lives on as his legacy.The Postman is first and foremost a beautiful love story: the shy postman seeking to win the love of the village belle. Love is a marvellous motivator to cause men to slay dragons, to fight fires, to do things they never dreamed possible. Love is in the heart of men and is at the core of God (1 Jn. 4:16). In the story, Mario's dragon is his timidity and he must conquer this to give voice to his emotions and feelings.

At one point in the film, Mario asks Neruda to explain poetry. In a gentle response, Neruda says: "When you explain poetry, it becomes banal. Better than any explanation is the experience of feelings that poetry can reveal to a nature open enough to understand it." Poetry is all about beauty and feelings. There is a power in a poem that cannot be captured by logical description or even prose. Neruda knows this. And he teaches Mario to become a poet like himself. Yet even knowing this, I find myself to be a philistine when it comes to poetry. Perhaps it is my scientific, rationalistic background, but I don't appreciate poetry. I may be one of those people who, as Neruda says, is not open to comprehend. Perhaps it will come with age and maturity.

At one point in the film, Mario asks Neruda to explain poetry. In a gentle response, Neruda says: "When you explain poetry, it becomes banal. Better than any explanation is the experience of feelings that poetry can reveal to a nature open enough to understand it." Poetry is all about beauty and feelings. There is a power in a poem that cannot be captured by logical description or even prose. Neruda knows this. And he teaches Mario to become a poet like himself. Yet even knowing this, I find myself to be a philistine when it comes to poetry. Perhaps it is my scientific, rationalistic background, but I don't appreciate poetry. I may be one of those people who, as Neruda says, is not open to comprehend. Perhaps it will come with age and maturity.Certainly The Postman underscores the power of words when combined in careful composition. Many are the martyrs who have died by the sword yet whose words continue, changing lives for decades or even centuries. Words have the power to transcend time and space.

The power of words is also a biblical concept. The writer of Hebrews says (4:12): "For the word of God is living and active. Sharper than any double-edged sword, it penetrates even to dividing soul and spirit, joints and marrow; it judges the thoughts and attitudes of the heart." The word of God here can do more than a normal sword. The word of God is also the means of creation. In Genesis 1, God spoke and his words brought into being the various aspects that we call creation.

The power of words is seen most clearly in the Word. John begins his gospel with a parallel to Genesis 1:

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was with God in the beginning. Through him all things were made; without him nothing was made that has been made. In him was life and that life was the light of men. (Jn. 1:1-4)Here, the Word is pointing to Jesus Christ, the Son of God. His is the power of life. He offers this life and his resurrection power to all will listen. John makes this clear just a few verses later (1:12): "Yet to all who received him, to those who believed in his name, he gave the right to become children of God." Whether you are a poetry-lover or a philistine, the power of words can impact you in a life-changing way if you embrace Jesus, the Word of God and master-poet!

Copyright ©2009, Martin Baggs

Happy-go-lucky describes Poppy to a tee. She is 30 and single, living with Zoe (Alexis Zegerman), a long-time friend. Where Zoe is cynical and sarcastic, Poppy is cheery and cheeky. She is playful and funny, and she brings this sense of vivaciousness to her job as a primary schoolteacher.

Happy-go-lucky describes Poppy to a tee. She is 30 and single, living with Zoe (Alexis Zegerman), a long-time friend. Where Zoe is cynical and sarcastic, Poppy is cheery and cheeky. She is playful and funny, and she brings this sense of vivaciousness to her job as a primary schoolteacher. In a way Mike Leigh offers two contrasting views of life. Poppy is carefree, ready to live on the edge, even talking to strangers. She is apparently happy with her life. Those around her act as foils. Her married but melancholy pregnant sister tells her she needs to get a mortgage, a marriage and kids. At her age, this is a must. But is it really? Scott, her driving instructor, reiterates this. He thinks she needs to settle down, she needs to behave like an adult. But Scott is a stressed out soul, who is visibly wound up tighter than a Swiss watch spring. Who is he to give this kind of advice to someone happier than himself?

In a way Mike Leigh offers two contrasting views of life. Poppy is carefree, ready to live on the edge, even talking to strangers. She is apparently happy with her life. Those around her act as foils. Her married but melancholy pregnant sister tells her she needs to get a mortgage, a marriage and kids. At her age, this is a must. But is it really? Scott, her driving instructor, reiterates this. He thinks she needs to settle down, she needs to behave like an adult. But Scott is a stressed out soul, who is visibly wound up tighter than a Swiss watch spring. Who is he to give this kind of advice to someone happier than himself? Leigh's film gives a number of interesting and funny vignettes into Poppy's life. Her adventures in driving drive Scott to the brink of sanity, though he doesn't quite jump off the edge. She jumps like a toddler on a trampoline. A friend takes her to Flamenco dance lessons where she stands out as a person willing to be different. She witnesses one of her students bullying another and intervenes as a friend more than a teacher and gets him help. She is a kind and generous person who has an overabundance to give to those around her. She has an optimism that is contagious.

Leigh's film gives a number of interesting and funny vignettes into Poppy's life. Her adventures in driving drive Scott to the brink of sanity, though he doesn't quite jump off the edge. She jumps like a toddler on a trampoline. A friend takes her to Flamenco dance lessons where she stands out as a person willing to be different. She witnesses one of her students bullying another and intervenes as a friend more than a teacher and gets him help. She is a kind and generous person who has an overabundance to give to those around her. She has an optimism that is contagious.

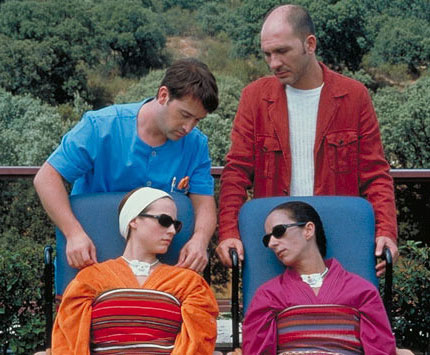

As the movie unfolds, it uses flashbacks to reveal layers of the principle characters. Benigni in particular is not what he appears. He seems to be benign and caring but he is delusional. The object of his love, the comatose Alicia, barely knows him. This love is unrequited. Benigni has manufactured a romance in his head and comes to believe in this fabrication. How much of our inner conversation, what we say to ourselves, is real? Do we ever delude ourselves into a affirming a reality that is a figment of our own imagination? To some degree, we do. We put our slant on what happens to us. We bring a subjective perspective to our life. That is all too evident in witness testimony in court where those who see the same event report it differently. Although some of that is simply subconscious, there is also the "spin" we put on things at work and at home so we appear better than we should. The more we spin, the more we believe our own press releases. This is dangerous, for us and others.

As the movie unfolds, it uses flashbacks to reveal layers of the principle characters. Benigni in particular is not what he appears. He seems to be benign and caring but he is delusional. The object of his love, the comatose Alicia, barely knows him. This love is unrequited. Benigni has manufactured a romance in his head and comes to believe in this fabrication. How much of our inner conversation, what we say to ourselves, is real? Do we ever delude ourselves into a affirming a reality that is a figment of our own imagination? To some degree, we do. We put our slant on what happens to us. We bring a subjective perspective to our life. That is all too evident in witness testimony in court where those who see the same event report it differently. Although some of that is simply subconscious, there is also the "spin" we put on things at work and at home so we appear better than we should. The more we spin, the more we believe our own press releases. This is dangerous, for us and others. The state of the two comatose women highlights the ethical dilemma medicine finds itself in today. The 2004 film Million Dollar Baby put boxer Maggie (Hilary Swank) in a quadriplegic position wishing to take her own life but unable to do so. Hence she pleaded with her trainer Frankie (Clint Eastwood) to do the unthinkable. Assisted suicide was the ethical conundrum. But Talk to Her puts the victim in a state where no conversation can occur. In a coma, the person lays as though dead. The question, then, becomes is she alive? What is life? And should it be maintained mechanically via medical technology, even if there appears to be no brain activity and no possibility of such? Is life more than the physical body?

The state of the two comatose women highlights the ethical dilemma medicine finds itself in today. The 2004 film Million Dollar Baby put boxer Maggie (Hilary Swank) in a quadriplegic position wishing to take her own life but unable to do so. Hence she pleaded with her trainer Frankie (Clint Eastwood) to do the unthinkable. Assisted suicide was the ethical conundrum. But Talk to Her puts the victim in a state where no conversation can occur. In a coma, the person lays as though dead. The question, then, becomes is she alive? What is life? And should it be maintained mechanically via medical technology, even if there appears to be no brain activity and no possibility of such? Is life more than the physical body?

In that time, life was hard and characterized by chores and duties. Marriages were arranged by parents, not based on love. Di's discovery of her new passion changes her approach to life. As the men build the school by hand, she weaves a red blanket by hand. This blanket will adorn the rafters as a sign of good luck. Additionally, when the building is finished, she continues to go to the old well to draw her water, since it gives her opportunity to pass the place where her love Changyu works. His voice beckons her, and she is drawn to it like a moth to a flame.

In that time, life was hard and characterized by chores and duties. Marriages were arranged by parents, not based on love. Di's discovery of her new passion changes her approach to life. As the men build the school by hand, she weaves a red blanket by hand. This blanket will adorn the rafters as a sign of good luck. Additionally, when the building is finished, she continues to go to the old well to draw her water, since it gives her opportunity to pass the place where her love Changyu works. His voice beckons her, and she is drawn to it like a moth to a flame. But love is at the heart of the relationship between Di and Changyu. It is clear to all. Eventually they are free to marry and establish a life together in the small village. The boy from the city becomes committed to a woman, a village and a vocation.

But love is at the heart of the relationship between Di and Changyu. It is clear to all. Eventually they are free to marry and establish a life together in the small village. The boy from the city becomes committed to a woman, a village and a vocation.

The story is simple. Michel (Martin LaSalle) is an unemployed and disaffected young intellectual, who may have just come out of prison. Bresson paints very few backstory details, so much is left to the interpretation of the viewer. He goes to the horse race-track to pick someone's pocket and gets caught by the police. Yet, without evidence they let him go. We see him as a thief right from the start. But he is lacking in the "art" of pickpocketry.

The story is simple. Michel (Martin LaSalle) is an unemployed and disaffected young intellectual, who may have just come out of prison. Bresson paints very few backstory details, so much is left to the interpretation of the viewer. He goes to the horse race-track to pick someone's pocket and gets caught by the police. Yet, without evidence they let him go. We see him as a thief right from the start. But he is lacking in the "art" of pickpocketry. Instead of taking up Jacques' offer of help, Michel becomes obsessed with stealing, picking pockets. When he finds a professional thief, he attaches himself to him, becoming his apprentice. Kassagi, who plays this thief, was an actual "sleight-of-hand" stage magician, and so some of the thievery tricks shown come from his stage act. There is a montage where these two work with a third pickpocket to hit multiple marks on a train and at a station. This scene is a breathtaking picture of the virtuosity of the thief.

Instead of taking up Jacques' offer of help, Michel becomes obsessed with stealing, picking pockets. When he finds a professional thief, he attaches himself to him, becoming his apprentice. Kassagi, who plays this thief, was an actual "sleight-of-hand" stage magician, and so some of the thievery tricks shown come from his stage act. There is a montage where these two work with a third pickpocket to hit multiple marks on a train and at a station. This scene is a breathtaking picture of the virtuosity of the thief.

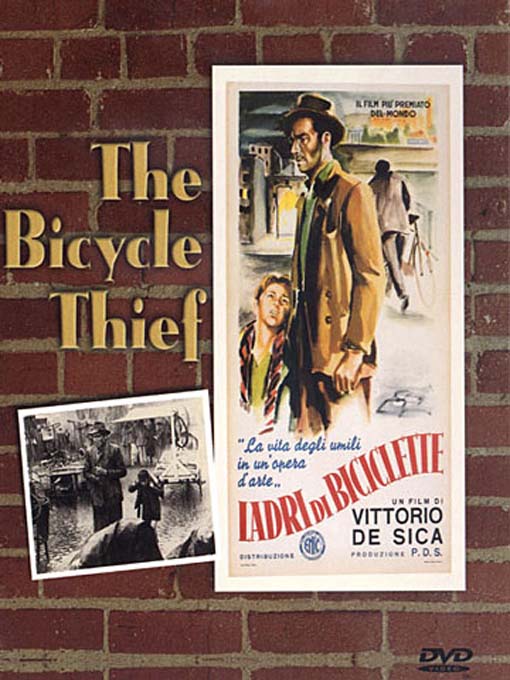

As Antonio prepares for work the next day, Antonio is happier than he has been in a long time. His son Bruno is clearly proud of his papa. There is a skip in Antonio's step and joy in the house. But soon into his first day, his bicycle is stolen. As he sees the thief getting away, Antonio chases him, hapless and helpless. Without a bike his job is in jeopardy and his dreams are shattered.

As Antonio prepares for work the next day, Antonio is happier than he has been in a long time. His son Bruno is clearly proud of his papa. There is a skip in Antonio's step and joy in the house. But soon into his first day, his bicycle is stolen. As he sees the thief getting away, Antonio chases him, hapless and helpless. Without a bike his job is in jeopardy and his dreams are shattered. The greatness of The Bicycle Thief comes from the interplay between father and son, especially as seen from the son's perspective. At first, it is clear that Bruno adores his dad. Antonio is his hero. When he gets the job, both are ecstatic. But that changes after his bike is stolen. Bruno still idolizes his dad, but as the search continues he sees his dad in a new light. Frustration and disappointment are not things a young son expects to see in his father.

The greatness of The Bicycle Thief comes from the interplay between father and son, especially as seen from the son's perspective. At first, it is clear that Bruno adores his dad. Antonio is his hero. When he gets the job, both are ecstatic. But that changes after his bike is stolen. Bruno still idolizes his dad, but as the search continues he sees his dad in a new light. Frustration and disappointment are not things a young son expects to see in his father. In the tragically beautiful conclusion, with all hope gone and thoroughly disheartened, Antonio sees his only way out -- to steal a bike himself. Sending Bruno home alone, he takes a bike, not knowing that Bruno missed the streetcar. Chased through the streets by a mob of honest men, Antonio is not fast enough to evade capture. And when he is caught, Bruno is there to see it for himself.

In the tragically beautiful conclusion, with all hope gone and thoroughly disheartened, Antonio sees his only way out -- to steal a bike himself. Sending Bruno home alone, he takes a bike, not knowing that Bruno missed the streetcar. Chased through the streets by a mob of honest men, Antonio is not fast enough to evade capture. And when he is caught, Bruno is there to see it for himself.

Another orphan, Latika, comes along and completes the trio. Latika and Jamal become fast friends, destined for more. But life is hard without parents. Moving to the city's huge trash piles, these three eke out a stinky living until a "savior" comes to rescue them and the other kids. But this is no true savior, this is a gangster who wants to exploit these kids as beggars for his own ends. It is here in the orphanage that Salim learns to use force to survive.

Another orphan, Latika, comes along and completes the trio. Latika and Jamal become fast friends, destined for more. But life is hard without parents. Moving to the city's huge trash piles, these three eke out a stinky living until a "savior" comes to rescue them and the other kids. But this is no true savior, this is a gangster who wants to exploit these kids as beggars for his own ends. It is here in the orphanage that Salim learns to use force to survive. At one point the Police Inspector tells Jamal, "Money and women. The reasons for most mistakes in life. Looks like you've mixed up both." But Jamal's cool and nerveless manner in the hot-seat under the TV lights is because he is not motivated by money. For many, the allure of winning the millions on this show is escape, an escape from a confining and constraining way of life. But, in contrast, Jamal is merely driven by hope, the hope of finding his life-long love, Latika.

At one point the Police Inspector tells Jamal, "Money and women. The reasons for most mistakes in life. Looks like you've mixed up both." But Jamal's cool and nerveless manner in the hot-seat under the TV lights is because he is not motivated by money. For many, the allure of winning the millions on this show is escape, an escape from a confining and constraining way of life. But, in contrast, Jamal is merely driven by hope, the hope of finding his life-long love, Latika. Ultimately, Jamal, a Muslim, believed in destiny. He believes "it's written," namely that he and Latika (Freida Pinto) would be together forever. Destiny, the irresistible course of events, is his dream. As a follower of Jesus, destiny is another term for the sovereign will of God (Rom. 8:28). God is in control of all events, some of which he has foretold in the prophets. The rest cannot be known ahead of time apart from his special revelation.

Ultimately, Jamal, a Muslim, believed in destiny. He believes "it's written," namely that he and Latika (Freida Pinto) would be together forever. Destiny, the irresistible course of events, is his dream. As a follower of Jesus, destiny is another term for the sovereign will of God (Rom. 8:28). God is in control of all events, some of which he has foretold in the prophets. The rest cannot be known ahead of time apart from his special revelation.

The plot becomes complex and multi-layered as Ferris discovers intel pointing to a safe house in Jordan. When he takes over the local CIA operation in that country, his arrogance emerges. But it is only a mirror of that of his boss, Hoffman. Both men are haughty, but Ferris comes from a perspective of having put his life on the line one too many times, while Hoffman believes he has a superior intellect. Theirs is a symbiotic relationship overlaying a mutual contempt.

The plot becomes complex and multi-layered as Ferris discovers intel pointing to a safe house in Jordan. When he takes over the local CIA operation in that country, his arrogance emerges. But it is only a mirror of that of his boss, Hoffman. Both men are haughty, but Ferris comes from a perspective of having put his life on the line one too many times, while Hoffman believes he has a superior intellect. Theirs is a symbiotic relationship overlaying a mutual contempt. After love and success comes truth. Salaam is a man who desires truth. He can work with complexity but cannot abide collusion, at least, where he is the one being deceived. He has the patience to wait for truth, unlike Hoffman whose impatience and in-your-face approach chases the truth away. Truth is indeed a good thing and should be pursued. Jesus said "I am the truth" (Jn. 14:6). In searching for truth we should look first to Christ. In waiting for truth, we should wait on the Lord (Psa. 37:7).

After love and success comes truth. Salaam is a man who desires truth. He can work with complexity but cannot abide collusion, at least, where he is the one being deceived. He has the patience to wait for truth, unlike Hoffman whose impatience and in-your-face approach chases the truth away. Truth is indeed a good thing and should be pursued. Jesus said "I am the truth" (Jn. 14:6). In searching for truth we should look first to Christ. In waiting for truth, we should wait on the Lord (Psa. 37:7).

Returning as a man to his youthful stomping grounds, Wallace (Mel Gibson) is overcome by the love of a woman, Murran (Catherine McCormack). But their secret marriage is barely begun before an English soldier tries to rape her. Wallace attacks and escapes but Murran is caught and executed as a warning to other Scots. With his love gone and his freedom threatened, Wallace's desire for revenge on the English and freedom for the Scots becomes the two driving raisons d'etre of his life.

Returning as a man to his youthful stomping grounds, Wallace (Mel Gibson) is overcome by the love of a woman, Murran (Catherine McCormack). But their secret marriage is barely begun before an English soldier tries to rape her. Wallace attacks and escapes but Murran is caught and executed as a warning to other Scots. With his love gone and his freedom threatened, Wallace's desire for revenge on the English and freedom for the Scots becomes the two driving raisons d'etre of his life. The battle scenes in Braveheart are spectacular. The camerawork gives the viewer a sense of being in the battle itself. With so much chaos and killing, it is hard to see who is who. Survival is first and foremost. Pretty, it is not. At the culmination of one battle, we see the dead and dying literally littering the battlefield that is soaking up their blood.

The battle scenes in Braveheart are spectacular. The camerawork gives the viewer a sense of being in the battle itself. With so much chaos and killing, it is hard to see who is who. Survival is first and foremost. Pretty, it is not. At the culmination of one battle, we see the dead and dying literally littering the battlefield that is soaking up their blood.

Moving ahead over a decade and it's election time in America. Marco is now a Major. Shaw is a congressman, whose mother Senator Eleanor Shaw (Streep) is pressing the Democratic Party to make her war-hero son the VP nominee instead of elder statesman Senator Jordan (Jon Voight). All seems well. Except Marco is having dreams, the same dream every night of that Kuwait battle. When another soldier (Jeffrey Wright) from his troop confesses to him that he is having this exact same dream, Marco begins to think there is a conspiracy.

Moving ahead over a decade and it's election time in America. Marco is now a Major. Shaw is a congressman, whose mother Senator Eleanor Shaw (Streep) is pressing the Democratic Party to make her war-hero son the VP nominee instead of elder statesman Senator Jordan (Jon Voight). All seems well. Except Marco is having dreams, the same dream every night of that Kuwait battle. When another soldier (Jeffrey Wright) from his troop confesses to him that he is having this exact same dream, Marco begins to think there is a conspiracy. Denzel Washington, always a solid actor, conveys palpably the panic and anxiety of a war veteran unsure of what is real. Schrieber balances the line between a cold killer and a fresh politician offering new hope to the American people. Streep is almost over-the-top as an over-controlling mother and megalomaniac politician bent on power.

Denzel Washington, always a solid actor, conveys palpably the panic and anxiety of a war veteran unsure of what is real. Schrieber balances the line between a cold killer and a fresh politician offering new hope to the American people. Streep is almost over-the-top as an over-controlling mother and megalomaniac politician bent on power. As The Manchurian Candidate plays out, it becomes clear someone has messed with the heads of Marco and Shaw. In the war on terror, politics has allied with business in an attempt to win this war. But winning a war by unethical means raises the question of means and ends. Is it right to accomplish moral ends by immoral means? At one point, a politician rebukes the executives of Manchuria Global: "My father, Tyler Prentiss, never asked, 'Is this okay? Is this okay?' He just did what needed to be done." Doing what needs to be done is focusing on the ends and not the means. Where are the checks and balances? Indeed, who defines what the ends are? They may be OK and laudable today, but as power wields its corrupting influence the ends may subtly become less OK tomorrow and immoral by next election year.

As The Manchurian Candidate plays out, it becomes clear someone has messed with the heads of Marco and Shaw. In the war on terror, politics has allied with business in an attempt to win this war. But winning a war by unethical means raises the question of means and ends. Is it right to accomplish moral ends by immoral means? At one point, a politician rebukes the executives of Manchuria Global: "My father, Tyler Prentiss, never asked, 'Is this okay? Is this okay?' He just did what needed to be done." Doing what needs to be done is focusing on the ends and not the means. Where are the checks and balances? Indeed, who defines what the ends are? They may be OK and laudable today, but as power wields its corrupting influence the ends may subtly become less OK tomorrow and immoral by next election year.

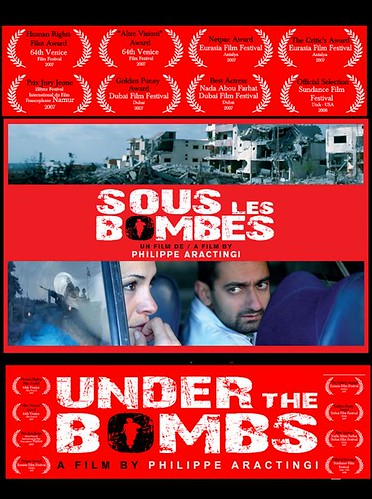

As they undertake this search, Zeina seems to have nothing in common with Tony. She is suffering the fear and anxiety of a parent missing a child. Yet, as the movie unfolds Aractingi makes it clear that they have more in common than they, or we, think. They are drawn together by their common humanity, the love, loss and grief that they have both experienced. Although Tony was initially attracted to Zeina's external beauty, he comes to see past this and eventually puts her needs and desires above his own. The turning point is when she moves from the back-seat of the taxi to the front-seat, to sit alongside him, to be more of a companion than a customer.

As they undertake this search, Zeina seems to have nothing in common with Tony. She is suffering the fear and anxiety of a parent missing a child. Yet, as the movie unfolds Aractingi makes it clear that they have more in common than they, or we, think. They are drawn together by their common humanity, the love, loss and grief that they have both experienced. Although Tony was initially attracted to Zeina's external beauty, he comes to see past this and eventually puts her needs and desires above his own. The turning point is when she moves from the back-seat of the taxi to the front-seat, to sit alongside him, to be more of a companion than a customer. What makes Under the Bombs compelling is the use of real people in a real war-zone. When we hear a bomb go off, it is an actual bomb, not a safe Hollywood explosive device. It took great risk from the two professional actors and the crew. In one scene, Tony asks if it is safe to walk across the rubble to talk to a couple, wondering if there are any cluster bombs under the bricks. Knowing this is real, we realize the actor is genuinely concerned about losing a limb or his life.

What makes Under the Bombs compelling is the use of real people in a real war-zone. When we hear a bomb go off, it is an actual bomb, not a safe Hollywood explosive device. It took great risk from the two professional actors and the crew. In one scene, Tony asks if it is safe to walk across the rubble to talk to a couple, wondering if there are any cluster bombs under the bricks. Knowing this is real, we realize the actor is genuinely concerned about losing a limb or his life.