Director: Joel Coen, 1991.

The Coen brothers are probably the most versatile film-makers working today. They write their own scripts; they direct the films; and they usually edit their own work under pseudonyms. They have made film noir (

Blood Simple,

The Man Who Wasn't There), comedy (

Raising Arizona, The Big Lebowski), bleak crime (

No Country for Old Men), even romantic comedy (

Intolerable Cruelty).

Barton Fink, their fourth film, defies simple genre identification. It starts as a drama with touches of comedy and ends as a surreal film noir. But it resists a simple narrative resolution and so is ambiguous and frustrating.

The Coens have won the biggest prize, the Best Film Oscar, for

No Country. But

Barton Fink achieved the distinction of winning the top three awards at the Cannes Film Festival: Best Actor (John Turturro), Best Director, and Palm D'Or (best picture). Indeed, after this, the Cannes organizers decreed that future films could win only two awards at most.

Barton Fink

Barton Fink opens in 1941 at the backstage of a Broadway play where playwright Barton Fink (Turturro) is watching the debut of his new play. It is a huge success, being appreciated by both the general audience and the critics. When he is offered serious money to move to Hollywood to become a script-writer for Capital Pictures he at first refuses. But with the influence of his agent, the money beckons and Barton goes.

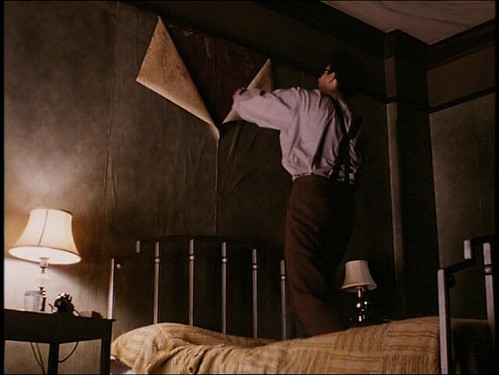

In Los Angeles Fink moves into the weird, seemingly abandoned Hotel Earle. Stylized in art-deco fashion, it seems to be full of residents and transients, yet Fink sees none except his sixth-floor neighbor, Charlie Meadows (John Goodman) a door-to-door insurance salesman. Hotel Earle is slowly decaying and has seen better days. Fink's room is bare of any decor except a cheap picture of a bikini-clad woman on the beach gazing into the surf. The picture is a key theme in the film, as Fink repeatedly stares at it, and the camera returns to it time and time again.

Barton Fink is filled with themes and symbols. The Coen brothers offer some clear contrasts particularly in the area of entertainment. Fink hails from New York, home of the theater and Broadway. This is high-culture. Works of art, these plays are labors of love that playwrights like Fink have struggled to produce. In contrast, Los Angeles is the home of Hollywood and low culture. Film-makers mechanically turn out formulaic B-movies to spin profits, not to make art. The audience they cater to is the plebeian, the philistine, not the connoisseur.

Watching

Barton Fink causes us to reflect on own preferences in entertainment. Do we prefer movies to stage-plays? Do we choose formulaic films, action, thrillers, rather than movies that might make us meditate? Are we looking for some form of escape from the daily grind or an encounter with the divine God?

Another inherent theme is the ideal of the common man. Fink is a leftist intellectual, and sees himself as the champion of these underprivileged people. Yet, ironically he is not one of them; instead he is self-obsessed and sees himself as a suffering creator. And he cannot see the common man when he is right in front of him. Charlie, his neighbor, is that archetype. Fat, sweaty, overly cheery and friendly, ready to share a drink and a joke, he is Common Man. But when Charlie says to Fink, "I could tell you some stories," Fink cuts him off and spouts off on his own soap-box. He will not listen.

Isolation, loneliness and frustration are additional themes. Fink spends most of his time in his room looking at his typewriter. He is struggling with writer's block having been ordered to write a wrestling movie script. Apparently surrounded by other hotel-dwellers, he is alone in one of the biggest cities in America. When he seeks the friendship of another writer, the famous W.P. Mayhew (John Mahoney), he discovers Mayhew is a drunk and something of a fraud, living with a lover Audrey (Judy Davis). Even these are not really his friends. He has no one to turn to. His agent is in New York. The movie producer is no help. And the mogul expects results not excuses.

When he turns to Audrey for help, late one night before a meeting with the film studio mogul, Fink is beside himself with worry. Her assistance is to reduce his tension. But when he awakes to a nightmare situation, the film itself becomes taut with tension and turns from a light drama to a darker film noir, with unexpected twists and turns.

Surrealism shows up in the eerie hotel. With an early reference to 666, the number of the beast in Revelation (Rev. 13:18), there is more to the hotel than meets the eye. Hotel Earle seems more like Hotel Hell. With New York symbolizing heaven (to Fink) LA symbolizes hell. Indeed, the hotel is hot as hell and the wallpaper in Fink's room starts to peel, dripping gooey paste like Charlie's pus-dripping ear infection. Yet, strangely this only seems to occur when Charlie is near. Is Charlie who he seems to be, a friendly pal? Or is he something more sinister? Is he perhaps the devil incarnate?

Certainly the character of Charlie Meadows reminds us that Satan is the master masquerader. He comes across looking like an angel of light (2 Cor. 11:14) yet is a demon of darkness. We do not expect to see the devil. He is portrayed as a little red demon with horns, a tail and a pitchfork. Yet he is more likely to come to us as a Charlie Meadows, the buddy next door, who wins our friendship and tempts us to turn from truth to sin. Only by standing firm in the strength of the Lord Jesus (Eph. 6:10-18) can we ordinary Jesus-followers expect to gain victory in the spiritual battle that we find ourselves in.

The most prominent theme in

Barton Fink is the process of writing. Fink struggles with writer's block for most of the film. He says to Charlie at one point, "I've always found that writing comes from great inner pain." But his inner pain and suffering cannot produce a script about wrestling. Even Charlie's help, as a former wrestler, is to no avail. Only when Charlie gives him a brown-paper wrapped box for storage, does his mind start working. The box becomes a sort of muse for Fink. Perhaps it is the suffering that comes in the second half of the film combined with this muse that finally enables Fink to turn out a screenplay in one long sitting. Even then, it is the story of a wrestler's soul-suffering, more intellectual than the B-movie script he is being paid for. It is a creation not a formulaic copy. In celebration he cries maniacally to a dancing throng, "I'm a writer, you monsters! I create! I create for a living! I'm a creator! I am a creator!"

In this statement Fink identifies one aspect of the image of God in humanity. God, the Creator, decided to create man and woman in his image as the very apex of his overall creation (Gen. 1:26). We are uniquely endowed with a soul and spirit. And we are given the ability to create. This can take many forms, such as the creation of art, of literature, of writings. These are to be enjoyed as reflections of the one primary Creator.

Toward the end, in another surrealistic scene, Fink sits on the beach and sees a beautiful woman in a bikini approach him. She sits next to him and gazes out at the surf in the identical pose to the woman in the picture in his room. Fink has moved into the picture and she has stepped into reality. This underscores the tension between the objective and the subjective points of view in art. The line between imagination and reality has blurred. The creator has become one with the creation. How real is art? How real are films?

This scene evokes the descent from heaven into our reality of the Creator. Jesus, the one who made and now sustains all that we see (Col. 1:16-17), left his position of glory to enter into his creation. He joined the story. He walked into the picture. He became one of us (Phil. 2:8). He took on human flesh, skin and bone. He did that so that he might offer himself in our place on the cross that was destined for each one of us. As Barton Fink entered into this pictorial creation, so Jesus Christ entered into his physical creation. But though

Barton Fink ends with an ambiguity that refuses to explain many of the symbols, Jesus stands ready with clear-cut options: life with him, heaven; death apart from him, hell.

Copyright ©2009, Martin Baggs

As with many French films, the pace is slow enough to allow characters to emerge. As they do, we begin to understand these two men. As opposite as they are, they have one thing in common: they are not satisfied with their lot in life.

As with many French films, the pace is slow enough to allow characters to emerge. As they do, we begin to understand these two men. As opposite as they are, they have one thing in common: they are not satisfied with their lot in life. Back at M. Manesquier's home, Milan sees two toothbrushes in the bathroom. He asks, "Why two combs and two toothbrushes?" Manesquier replies, "There are two kinds of men. Those who say, 'I must buy a toothbrush; I've lost mine," they're adventurers. And those who have an extra tooth brush. . . . Planners, at best." Here is the central contrast of the film: planners and adventurers. Manesquier had been a planner his whole life, surrounded by a library filled with books, reading his poetry, teaching his students. His life was uneventful. Even when he tries to pick a fight, he fails. Milan, on the other hand, is no planner; he has adventure to spare robbing banks. But both are bored with their lives and want what the other one has. Excitement for equanimity. As the climax arrives we wonder if they got what they wanted.

Back at M. Manesquier's home, Milan sees two toothbrushes in the bathroom. He asks, "Why two combs and two toothbrushes?" Manesquier replies, "There are two kinds of men. Those who say, 'I must buy a toothbrush; I've lost mine," they're adventurers. And those who have an extra tooth brush. . . . Planners, at best." Here is the central contrast of the film: planners and adventurers. Manesquier had been a planner his whole life, surrounded by a library filled with books, reading his poetry, teaching his students. His life was uneventful. Even when he tries to pick a fight, he fails. Milan, on the other hand, is no planner; he has adventure to spare robbing banks. But both are bored with their lives and want what the other one has. Excitement for equanimity. As the climax arrives we wonder if they got what they wanted.

Through a series of flashbacks we see the "development" of this family. At an early age mom Sara (Cameron Diaz) and dad (Jason Patric) are told that young Kate has the disease. Their doctor tells them, off-the-record, that a genetically engineering child would be a perfect match for blood and bone marrow transplants. Of course, ethically he is not allowed to make such a recommendation or even suggestion. But Sara snags this ray of hope in her suddenly dark world and along comes Anna. Made as a spare parts child, Anna is her sister's keeper in the real physical sense.

Through a series of flashbacks we see the "development" of this family. At an early age mom Sara (Cameron Diaz) and dad (Jason Patric) are told that young Kate has the disease. Their doctor tells them, off-the-record, that a genetically engineering child would be a perfect match for blood and bone marrow transplants. Of course, ethically he is not allowed to make such a recommendation or even suggestion. But Sara snags this ray of hope in her suddenly dark world and along comes Anna. Made as a spare parts child, Anna is her sister's keeper in the real physical sense. So it is a surprise to Sara when she is delivered a subpoena to appear in court. She is being sued by her own daughter Anna, who wants medical emancipation from her parents so she does not have to struggle and suffer the pain and possible long-term effects of further operations in support of her sister. Anna has contracted the support of showboat lawyer Campbell Alexander (Alec Baldwin).

So it is a surprise to Sara when she is delivered a subpoena to appear in court. She is being sued by her own daughter Anna, who wants medical emancipation from her parents so she does not have to struggle and suffer the pain and possible long-term effects of further operations in support of her sister. Anna has contracted the support of showboat lawyer Campbell Alexander (Alec Baldwin). My Sister's Keeper is not perfect, by any means. It veers into sentimentality at points and gross-out imagery at others. Its nonlinear narrative enables it to gloss over a number of plot holes quickly and quietly. It underplays the male characters to overplay the three female leads. And it traverses a fairly predictable and emotionally depressing path only to add a snippet of Hollywood hope at the end.

My Sister's Keeper is not perfect, by any means. It veers into sentimentality at points and gross-out imagery at others. Its nonlinear narrative enables it to gloss over a number of plot holes quickly and quietly. It underplays the male characters to overplay the three female leads. And it traverses a fairly predictable and emotionally depressing path only to add a snippet of Hollywood hope at the end.

Eldorado has some very funny moments, but is filled with absurdity along the way. Lanners brings some bizarre characters into the film for distinct episodes but some of them feel overly contrived, such as the naked camper and the hugger. In the end, it is more sick and sad than funny and fulfilling.

Eldorado has some very funny moments, but is filled with absurdity along the way. Lanners brings some bizarre characters into the film for distinct episodes but some of them feel overly contrived, such as the naked camper and the hugger. In the end, it is more sick and sad than funny and fulfilling.

Juxtaposed against this story is the main plot, that of black man Robinson. He is accused of raping Mayella (Collin Wilcox). Finch is asked to defend him and agrees, much to the consternation of the town community. And his kids, Scout and Jem, initially take the brunt of the town's scorn. When Scout asks him why he is defending Robinson if no one wants him to, Finch responds, "For a number of reasons. The main one is that if I didn't, I couldn't hold my head up in town. I couldn't even tell you or Jem not to do somethin' again."

Juxtaposed against this story is the main plot, that of black man Robinson. He is accused of raping Mayella (Collin Wilcox). Finch is asked to defend him and agrees, much to the consternation of the town community. And his kids, Scout and Jem, initially take the brunt of the town's scorn. When Scout asks him why he is defending Robinson if no one wants him to, Finch responds, "For a number of reasons. The main one is that if I didn't, I couldn't hold my head up in town. I couldn't even tell you or Jem not to do somethin' again." As the film progresses, the courtroom scene dominates. The all-white jury looks upon the black defendant and the guilty verdict is a foregone conclusion, so it seems. Robinson is on trial for his life and Finch gives him a stellar defense. But he is no idealist. In his closing statement, he declares to the all-male jury, "Now, gentlemen, in this country, our courts are the great levelers. In our courts, all men are created equal. I'm no idealist to believe firmly in the integrity of our courts and of our jury system -- that's no ideal to me. That is a living, working reality." This is an impassioned speech, not a prevarication, from a man of principle.

As the film progresses, the courtroom scene dominates. The all-white jury looks upon the black defendant and the guilty verdict is a foregone conclusion, so it seems. Robinson is on trial for his life and Finch gives him a stellar defense. But he is no idealist. In his closing statement, he declares to the all-male jury, "Now, gentlemen, in this country, our courts are the great levelers. In our courts, all men are created equal. I'm no idealist to believe firmly in the integrity of our courts and of our jury system -- that's no ideal to me. That is a living, working reality." This is an impassioned speech, not a prevarication, from a man of principle.

Andrew, on the other hand, is a sycophant, sucking up to his boss as a way to advance. His dream is to be an editor like her, and he sees her as his meal ticket. He will do anything, sacrifice time with his family, to make progress in this ambition. Where Margaret is a witch, Andrew is a wimp. But when she tells her bosses that she is marrying him, that is close to the limit. He is ready to opt out of this one until Margaret tells him he will lose his job the minute she is deported and all his efforts will have been in vain. Not surprisingly he agrees.

Andrew, on the other hand, is a sycophant, sucking up to his boss as a way to advance. His dream is to be an editor like her, and he sees her as his meal ticket. He will do anything, sacrifice time with his family, to make progress in this ambition. Where Margaret is a witch, Andrew is a wimp. But when she tells her bosses that she is marrying him, that is close to the limit. He is ready to opt out of this one until Margaret tells him he will lose his job the minute she is deported and all his efforts will have been in vain. Not surprisingly he agrees. But The Proposal also highlights some positive values. Fletcher surrounds Andrew with family and friends who love him and miss him. This family is not perfect but it is his family. Grace (Mary Steenburgen) is a mother who wants the best for her boy. Joe (Craig T. Nelson) is a father who thinks he knows what is best for his boy but does not really know Andrew. There is a rift in their relationship that no quick father-son talk can heal. And there is Grandma Annie (Betty White). Betty White gets the funniest lines and is terrific as the all-wise grandma who knows more than she lets on. The only weird thing is her mother earth worship, a take on Native American religion, that appears totally unnecessary except to let Bullock shake her booty.

But The Proposal also highlights some positive values. Fletcher surrounds Andrew with family and friends who love him and miss him. This family is not perfect but it is his family. Grace (Mary Steenburgen) is a mother who wants the best for her boy. Joe (Craig T. Nelson) is a father who thinks he knows what is best for his boy but does not really know Andrew. There is a rift in their relationship that no quick father-son talk can heal. And there is Grandma Annie (Betty White). Betty White gets the funniest lines and is terrific as the all-wise grandma who knows more than she lets on. The only weird thing is her mother earth worship, a take on Native American religion, that appears totally unnecessary except to let Bullock shake her booty. Four days with the almost-all-American, certainly all-Alaskan, Paxtons, is more than Margaret wants or thinks she can handle. But over this time, dealing with dial-up connections and flying dogs, her cynical shell cracks. And lo and behold we see a real person trying to get out. She sees a real family, warts and all. There is even a trip to the woodshed for a verbal spanking. And just as Margaret's character softens, so too does Andrew's. He becomes stronger, more determined, and willing to risk loss for what he really wants.

Four days with the almost-all-American, certainly all-Alaskan, Paxtons, is more than Margaret wants or thinks she can handle. But over this time, dealing with dial-up connections and flying dogs, her cynical shell cracks. And lo and behold we see a real person trying to get out. She sees a real family, warts and all. There is even a trip to the woodshed for a verbal spanking. And just as Margaret's character softens, so too does Andrew's. He becomes stronger, more determined, and willing to risk loss for what he really wants.

Another inherent theme is the ideal of the common man. Fink is a leftist intellectual, and sees himself as the champion of these underprivileged people. Yet, ironically he is not one of them; instead he is self-obsessed and sees himself as a suffering creator. And he cannot see the common man when he is right in front of him. Charlie, his neighbor, is that archetype. Fat, sweaty, overly cheery and friendly, ready to share a drink and a joke, he is Common Man. But when Charlie says to Fink, "I could tell you some stories," Fink cuts him off and spouts off on his own soap-box. He will not listen.

Another inherent theme is the ideal of the common man. Fink is a leftist intellectual, and sees himself as the champion of these underprivileged people. Yet, ironically he is not one of them; instead he is self-obsessed and sees himself as a suffering creator. And he cannot see the common man when he is right in front of him. Charlie, his neighbor, is that archetype. Fat, sweaty, overly cheery and friendly, ready to share a drink and a joke, he is Common Man. But when Charlie says to Fink, "I could tell you some stories," Fink cuts him off and spouts off on his own soap-box. He will not listen. Surrealism shows up in the eerie hotel. With an early reference to 666, the number of the beast in Revelation (Rev. 13:18), there is more to the hotel than meets the eye. Hotel Earle seems more like Hotel Hell. With New York symbolizing heaven (to Fink) LA symbolizes hell. Indeed, the hotel is hot as hell and the wallpaper in Fink's room starts to peel, dripping gooey paste like Charlie's pus-dripping ear infection. Yet, strangely this only seems to occur when Charlie is near. Is Charlie who he seems to be, a friendly pal? Or is he something more sinister? Is he perhaps the devil incarnate?

Surrealism shows up in the eerie hotel. With an early reference to 666, the number of the beast in Revelation (Rev. 13:18), there is more to the hotel than meets the eye. Hotel Earle seems more like Hotel Hell. With New York symbolizing heaven (to Fink) LA symbolizes hell. Indeed, the hotel is hot as hell and the wallpaper in Fink's room starts to peel, dripping gooey paste like Charlie's pus-dripping ear infection. Yet, strangely this only seems to occur when Charlie is near. Is Charlie who he seems to be, a friendly pal? Or is he something more sinister? Is he perhaps the devil incarnate? The most prominent theme in Barton Fink is the process of writing. Fink struggles with writer's block for most of the film. He says to Charlie at one point, "I've always found that writing comes from great inner pain." But his inner pain and suffering cannot produce a script about wrestling. Even Charlie's help, as a former wrestler, is to no avail. Only when Charlie gives him a brown-paper wrapped box for storage, does his mind start working. The box becomes a sort of muse for Fink. Perhaps it is the suffering that comes in the second half of the film combined with this muse that finally enables Fink to turn out a screenplay in one long sitting. Even then, it is the story of a wrestler's soul-suffering, more intellectual than the B-movie script he is being paid for. It is a creation not a formulaic copy. In celebration he cries maniacally to a dancing throng, "I'm a writer, you monsters! I create! I create for a living! I'm a creator! I am a creator!"

The most prominent theme in Barton Fink is the process of writing. Fink struggles with writer's block for most of the film. He says to Charlie at one point, "I've always found that writing comes from great inner pain." But his inner pain and suffering cannot produce a script about wrestling. Even Charlie's help, as a former wrestler, is to no avail. Only when Charlie gives him a brown-paper wrapped box for storage, does his mind start working. The box becomes a sort of muse for Fink. Perhaps it is the suffering that comes in the second half of the film combined with this muse that finally enables Fink to turn out a screenplay in one long sitting. Even then, it is the story of a wrestler's soul-suffering, more intellectual than the B-movie script he is being paid for. It is a creation not a formulaic copy. In celebration he cries maniacally to a dancing throng, "I'm a writer, you monsters! I create! I create for a living! I'm a creator! I am a creator!" Toward the end, in another surrealistic scene, Fink sits on the beach and sees a beautiful woman in a bikini approach him. She sits next to him and gazes out at the surf in the identical pose to the woman in the picture in his room. Fink has moved into the picture and she has stepped into reality. This underscores the tension between the objective and the subjective points of view in art. The line between imagination and reality has blurred. The creator has become one with the creation. How real is art? How real are films?

Toward the end, in another surrealistic scene, Fink sits on the beach and sees a beautiful woman in a bikini approach him. She sits next to him and gazes out at the surf in the identical pose to the woman in the picture in his room. Fink has moved into the picture and she has stepped into reality. This underscores the tension between the objective and the subjective points of view in art. The line between imagination and reality has blurred. The creator has become one with the creation. How real is art? How real are films?

As a father, Evan is a washout. He cannot relate to Olivia and he doesn't really want to. We wonder whatever prompted him to become a parent in the first place, but that is never answered. He pleads with his daughter constantly, asking her to be quiet, to go to bed, to stop screaming (which she does whenever someone takes her security blanket away). But parents are supposed to lead their kids not plead with them. He has no parental control; he exercises no parental leadership.

As a father, Evan is a washout. He cannot relate to Olivia and he doesn't really want to. We wonder whatever prompted him to become a parent in the first place, but that is never answered. He pleads with his daughter constantly, asking her to be quiet, to go to bed, to stop screaming (which she does whenever someone takes her security blanket away). But parents are supposed to lead their kids not plead with them. He has no parental control; he exercises no parental leadership. That brings us to the security blanket.

That brings us to the security blanket.

At one point Ryder comments to Garber, "When you put your socks on this morning, did you think your day would be like this?" It all seems like a joke, a caper to him. But he is sitting next to a kidnapped driver and there is a dead cop behind him. This is no joke.

At one point Ryder comments to Garber, "When you put your socks on this morning, did you think your day would be like this?" It all seems like a joke, a caper to him. But he is sitting next to a kidnapped driver and there is a dead cop behind him. This is no joke. Character and patience Barber has, but he also has a darker secret. When Ryder discovers this he exploits it to his advantage. His banter with Garber turns into psychotic counseling. His cubicle becomes a confessional booth. Garber must confess publicly or Ryder will kill an innocent hostage.

Character and patience Barber has, but he also has a darker secret. When Ryder discovers this he exploits it to his advantage. His banter with Garber turns into psychotic counseling. His cubicle becomes a confessional booth. Garber must confess publicly or Ryder will kill an innocent hostage.

Abrahams is a man with a chip on his shoulder: prejudice. When asked, by his girlfriend Sybil, about his running, why he runs, he answers, "I'm more of an addict. It's a compulsion with me, a weapon I can use." Sybil asks, "Against what?" and he responds, "Being Jewish I suppose." He had experienced the religious prejudice of a Jew living in a "Christian" nation, and fought against this with his natural ability. By winning he could "prove himself" and his faith. He was no worse than the rest; indeed, he would be better because he was number one.

Abrahams is a man with a chip on his shoulder: prejudice. When asked, by his girlfriend Sybil, about his running, why he runs, he answers, "I'm more of an addict. It's a compulsion with me, a weapon I can use." Sybil asks, "Against what?" and he responds, "Being Jewish I suppose." He had experienced the religious prejudice of a Jew living in a "Christian" nation, and fought against this with his natural ability. By winning he could "prove himself" and his faith. He was no worse than the rest; indeed, he would be better because he was number one. Liddell makes this point clearly, in an evangelistic address to a group of spectators after he wins a race in England. "You came to see a race today. . . . But I want you do more than just watch a race. I want you to take part in it. I want to compare faith to running in a race." The writer to the Hebrews says essentially the same thing: "Let us run with perseverance the race marked out for us" (Heb. 12:1). Unlike the sprints that Abrahams and Liddell ran, our race of faith is more of a marathon requiring endurance and lots of training. We can choose to begin this race the day we embrace our great trainer and coach, Jesus Christ. We will face obstacles. We will hit "the wall" that all marathoners hit once the initial energy burst has dissipated. But with grace we can push onwards to the finish line, the end of our earthly life, where we will be crowned as winners by Jesus himself (Rev. 2:10)!

Liddell makes this point clearly, in an evangelistic address to a group of spectators after he wins a race in England. "You came to see a race today. . . . But I want you do more than just watch a race. I want you to take part in it. I want to compare faith to running in a race." The writer to the Hebrews says essentially the same thing: "Let us run with perseverance the race marked out for us" (Heb. 12:1). Unlike the sprints that Abrahams and Liddell ran, our race of faith is more of a marathon requiring endurance and lots of training. We can choose to begin this race the day we embrace our great trainer and coach, Jesus Christ. We will face obstacles. We will hit "the wall" that all marathoners hit once the initial energy burst has dissipated. But with grace we can push onwards to the finish line, the end of our earthly life, where we will be crowned as winners by Jesus himself (Rev. 2:10)! After his loss to Liddell, Abrahams hires a professional trainer Sam Mussabini (Ian Holm, better known as Bilbo Baggins in the Lord of the Rings trilogy, but Oscar-nominated here). With his help, Abrahams makes it through the heats to the final of the 100m sprint in Paris. He is on his way to success. Liddell, though, discovers that the heats of this race occur on a Sunday. As a devout follower of Christ, he is not willing to compromise his belief that the Sabbath should be kept for worship alone."God made countries, God made kings, and the rules by which they govern. And these rules say that the Sabbath is His." Despite enormous pressure to cave, he remained true to his principles. Even the Prince of Wales could not persuade him. He followed his conscience. And as he did for Abraham in his hour of testing with Isaac (Gen. 22), God provided a way out.

After his loss to Liddell, Abrahams hires a professional trainer Sam Mussabini (Ian Holm, better known as Bilbo Baggins in the Lord of the Rings trilogy, but Oscar-nominated here). With his help, Abrahams makes it through the heats to the final of the 100m sprint in Paris. He is on his way to success. Liddell, though, discovers that the heats of this race occur on a Sunday. As a devout follower of Christ, he is not willing to compromise his belief that the Sabbath should be kept for worship alone."God made countries, God made kings, and the rules by which they govern. And these rules say that the Sabbath is His." Despite enormous pressure to cave, he remained true to his principles. Even the Prince of Wales could not persuade him. He followed his conscience. And as he did for Abraham in his hour of testing with Isaac (Gen. 22), God provided a way out. Once more Liddell's life gives an example of what it means to follow your conscience. Many followers of Jesus would not hold the same conviction as Liddell about Sabbath-keeping. But Paul tells us, "Each one should be fully convinced in his own mind" (Rom. 14:5). If it is wrong for us, we need to follow our conscience. We need not hold others accountable to our own conscience-held beliefs. But we must hold ourselves true to what the Holy Spirit has spoken to our consciences.

Once more Liddell's life gives an example of what it means to follow your conscience. Many followers of Jesus would not hold the same conviction as Liddell about Sabbath-keeping. But Paul tells us, "Each one should be fully convinced in his own mind" (Rom. 14:5). If it is wrong for us, we need to follow our conscience. We need not hold others accountable to our own conscience-held beliefs. But we must hold ourselves true to what the Holy Spirit has spoken to our consciences.

The day that great war (World War I) ended in 1918 was the day that Benjamin Button was borb. And it was the same fateful day his mother died in childbirth. When his father sees him, a monster looking like an old man in a baby's frame, something happens. He snaps. He picks up the baby and wanders the streets of the Big Easy, before leaving him on the porch steps of a house. Queenie (Taraji Henson), a black woman who runs a retirement home, finds him and keeps him as her own white child.

The day that great war (World War I) ended in 1918 was the day that Benjamin Button was borb. And it was the same fateful day his mother died in childbirth. When his father sees him, a monster looking like an old man in a baby's frame, something happens. He snaps. He picks up the baby and wanders the streets of the Big Easy, before leaving him on the porch steps of a house. Queenie (Taraji Henson), a black woman who runs a retirement home, finds him and keeps him as her own white child. Loneliness permeates the lives of many people today, regardless of their social situation. They may be single, they may be married. A person can be surrounded by people and still feel alone. Button learned to accept this loneliness, to live with it, to embrace it. We all will experience loneliness in our lives. How we deal with it will say much about our character. One temporary resident in the house, a pygmy, tells Button to not be afraid of his loneliness. And this is a message for us. If we embrace Jesus, then we can cling to the promise he gives us that he will never leave us or forsake us (Matt. 28:20). Even in our loneliest moments, we can count on Jesus as an ever-present friend.

Loneliness permeates the lives of many people today, regardless of their social situation. They may be single, they may be married. A person can be surrounded by people and still feel alone. Button learned to accept this loneliness, to live with it, to embrace it. We all will experience loneliness in our lives. How we deal with it will say much about our character. One temporary resident in the house, a pygmy, tells Button to not be afraid of his loneliness. And this is a message for us. If we embrace Jesus, then we can cling to the promise he gives us that he will never leave us or forsake us (Matt. 28:20). Even in our loneliest moments, we can count on Jesus as an ever-present friend. As he grows, Button (Brad Pitt) starts to realize there is life outside Queenie's house. He takes a job on a tug-boat and sees the world. He serves in the navy on this boat during WW2. Throughout, he remains in love with Daisy, the young girl he met years ago. When he comes home he sees her in all her beauty. Their love affair is the heart and soul of the story. But it is one that is destined to end because of Button's curious aging.

As he grows, Button (Brad Pitt) starts to realize there is life outside Queenie's house. He takes a job on a tug-boat and sees the world. He serves in the navy on this boat during WW2. Throughout, he remains in love with Daisy, the young girl he met years ago. When he comes home he sees her in all her beauty. Their love affair is the heart and soul of the story. But it is one that is destined to end because of Button's curious aging.

Kim gets to go with her friend but as soon as they arrive at their Paris apartment, she realizes her friend has lied to her. And within minutes, both are abducted, taken by unseen men. They have become the targets of an Albanian mafia group, intent on addicting them to drugs and then forcing them into a life of prostitution or selling them as sex slaves: a hell on earth.

Kim gets to go with her friend but as soon as they arrive at their Paris apartment, she realizes her friend has lied to her. And within minutes, both are abducted, taken by unseen men. They have become the targets of an Albanian mafia group, intent on addicting them to drugs and then forcing them into a life of prostitution or selling them as sex slaves: a hell on earth. If the deceit of the daughter got Kim into this impossible situation, it's the skills of the father that will get her out. As the kidnapping is underway, Kim is on the phone to her dad. And so Mills hears first-hand what is happening to his little girl. When the call is finally discovered, Mills tells her kidnapper:

If the deceit of the daughter got Kim into this impossible situation, it's the skills of the father that will get her out. As the kidnapping is underway, Kim is on the phone to her dad. And so Mills hears first-hand what is happening to his little girl. When the call is finally discovered, Mills tells her kidnapper: As Mills goes on the offensive, he is willing to do anything to find his daughter, even if that means resorting to the level of those he is hunting.

As Mills goes on the offensive, he is willing to do anything to find his daughter, even if that means resorting to the level of those he is hunting.