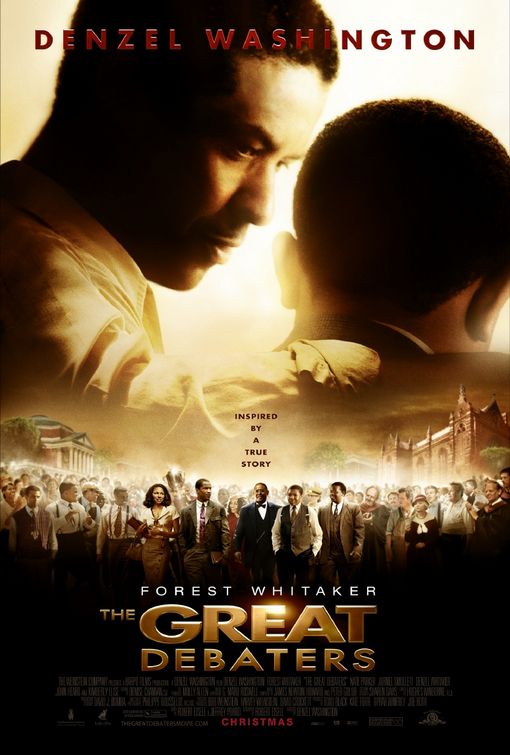

Director: Denzel Washington, 2007.

"An unjust law is no law at all." Saint Augustine said this line two millenia ago. And it is one of the key lines and themes of this uplifting movie which uses the vehicle of racial separatism in debate competition to highlight separatism on the national scale.

Based on real events, The Great Debaters is set in rural Texas in the mid 1930s. Amidst the Great Depression, Marshall is the location of Wiley College, a black school where Melvin Tolson (Denzel Washington) teaches and coaches the debate team. When he has try-outs, the four students who make the team are diverse even if all black: Henry Lowe (Nate Parker), an older roguish youth; Hamilton Burgess (Jermaine Williams), a conservative returning debater; James Farmer Jr (Denzel Whitaker), the precocious 14-year-old son of the principal Dr. James Farmer Sr (Forrest Whitaker); and Samantha Booke (Jurnee Smollett), the attractive interest of both James and Henry.

The young actors give outstanding performances, even alongside screen veteran and Oscar winners, Washington and Whitaker. Interestingly, young Denzel Whitaker is named after Denzel Washington but is no relation to Forest Whitaker. But, despite the movie's ethical themes, argued in debate format, it is ultimately lightweight devoid of intellectual depth or argument.

The young actors give outstanding performances, even alongside screen veteran and Oscar winners, Washington and Whitaker. Interestingly, young Denzel Whitaker is named after Denzel Washington but is no relation to Forest Whitaker. But, despite the movie's ethical themes, argued in debate format, it is ultimately lightweight devoid of intellectual depth or argument.As the movie starts we see Tolson, dressed as a humble field worker, breaking up a fight at an illicit party and preventing Lowe from slashing a man. The next time we see him, Tolson is in a classroom and Lowe is one of his students. There is history between these two, a history that will work its way through the film until the final conclusion.

The town of Marshall is still living as though the Civil War had missed it completely. Racism is alive and well. Blacks are separated from whites, and must act in a servile manner despite having superior intellect in many cases. One scene highlights this, when Farmer Sr hits and kills a hog owned by a redneck. Ordinarily this would be considered a minor car accident, but as a black he is essentially blackmailed into making excessive recompense. He has no recourse or alternative.

In one scene that is graphic and shocking, a lynch mob has burned and strung up a black man. Tolson and his debate team witness this shocking spectacle and barely escape with their lives. It begs the question what crime warrants the rule of mob justice? How can killing a man like this be defended? The Old Testament makes it clear, "You shall not murder" (Exod. 20:13). There is a place for judicial punishment administered by the state (Rom. 13) but even there injustice is sometimes present. As God-fearing followers of Jesus, we can never condone this kind of violence brought on by blood-lust and mob psychology.

As the debate team is formed it needs Tolson's teachings on elocution and discipline. Further, it relies on his development of debate position and logic. But as the team starts winning, the young debaters' confidence soars and they yearn to define their own arguments. As they win against the top black colleges of the time, Tolson wants them to compete against white schools.

As the debate team is formed it needs Tolson's teachings on elocution and discipline. Further, it relies on his development of debate position and logic. But as the team starts winning, the young debaters' confidence soars and they yearn to define their own arguments. As they win against the top black colleges of the time, Tolson wants them to compete against white schools.When they get the chance, Samantha also gets her chance to debate. Arguing that blacks should have the opportunity to go to the same colleges as whites, she plumbs an emotional depth and concludes, "the time for justice, the time for freedom, and the time for equality is always, is always right now!" The injustice of the separatist laws of the country screamed out with her. Why couldn't these highly intelligent young people go to the same colleges as their white counterparts and competitors?

Ethically and morally, we can look back 70 years and see the injustice of the era. Biblically we know that black and white are both equally human, neither intrinsically better than the other. We are all the same in our fundamental human nature, created in the image of God (Gen. 1:26). We are the same in our redeemed nature, saved by Jesus and progressively conformed to his likeness (Rom. 8:28-30). As Paul said in his letter to the church in Galatia, "There is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus" (Gal. 3:28).

When circumstances conspire against Tolson and his team, he is black-balled and white colleges start to rescind their invitations to debate. All appears lost. But then Tolson gives them his pep talk. Never quit, he tells them. Failure can make them stronger. For those viewed as second class citizens accustomed to the scraps, this is good advice. They can use failure to their advantage. But this advice is sage indeed, even for us today. Success can blind us and make us complacent. We learn better from our mistakes and our failures than from a surfeit of success.

The Great Debaters moves inexorably to the culminating debate with Harvard, the first time a black school had debated the national debating champions. It is in this debate on civil disobedience that Farmer Jr emotionally draws on personal experience and then calls on Augustine: "In Texas they lynch Negroes. . . . St Augustine said, 'An unjust law is no law at all.' Which means I have a right, even a duty to resist."

There is indeed a place for civil disobedience. When justice cannot be found in the courts of the land, and when injustice is occurring in the streets and the fields, people have an obligation to resist. The apostles knew this. When they were told to refrain from teaching and preaching Christ (Acts 4) they refused to do so. They disobeyed without violence but paid the price with jail time (Acts 5:18). In their defense they declared, "We must obey God rather than men!" (Acts 5:29). God had commanded them to love others and share Jesus. There was no violence in their acts of disobedience.

The Great Debaters leaves us contemplating the need for justice and equality, and helps us reflect on the place of civil disobedience. There might come a time when, like the Apostle Peter, we will face a decision to obey God rather than men.

Copyright 2009, Martin Baggs

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete