Director: Charles Laughton, 1955. (NR)

"Watch out for false prophets. They come to you in sheep's clothing, but inwardly they are ferocious wolves. By their fruit you will recognize them. Do people pick grapes from thornbushes, or figs from thistles? Likewise every good tree bears good fruit, but a bad tree bears bad fruit. A good tree cannot bear bad fruit, and a bad tree cannot bear good fruit. Every tree that does not bear good fruit is cut down and thrown into the fire. Thus, by their fruit you will recognize them." (Matt. 7:15-20)Rachel Cooper (Lillian Gish) reads these words from Scripture (in the KJV ) to a group of children as the opening credits roll. We don't know who this matronly woman is, though she looks like a Sunday School teacher. But she will appear again towards the end of the film. Yet, this warning frames the film, giving us a portent of things to come.

The hunter is Reverend Harry Powell (Robert Mitchum), a tall and handsome "preacher" whose knuckles are tattooed with LOVE on one hand and HATE on the other. This dichotomy perfectly describes this psychopathic Bluebeard, who professes a gospel of love but really brings a gospel of hate. He seeks lonely wealthy widows so he can marry and then kill them for their money, somehow believing he is doing God's will.

The hunter is Reverend Harry Powell (Robert Mitchum), a tall and handsome "preacher" whose knuckles are tattooed with LOVE on one hand and HATE on the other. This dichotomy perfectly describes this psychopathic Bluebeard, who professes a gospel of love but really brings a gospel of hate. He seeks lonely wealthy widows so he can marry and then kill them for their money, somehow believing he is doing God's will.Robert Mitchum is at the top of his acting game here as the creepy killer. Charles Laughton, the great actor from the 30s-50s directed but had such a bad experience that this was his second and last attempt at directing. Yet, despite the poor critical and commercial reception at its release, this has aged well and is a spellbinding chiller that is suspenseful without resorting to violence and gore.

Early in the film Harry is in prison sharing a cell with killer Ben Harper (Peter Graves, from the TV series "Mission Impossible"). It is the Great Depression, and Ben stole $10,000 to feed his kids. That money is hidden and only his two young children John and Pearl know where it is. Even his wife Willa (Shelley Winters) has no idea. She thinks it is gone, thrown into the river. When Ben is hanged, Willa becomes the next widow on Harry's list.

When Harry comes to the small town where Willa lives, it is his sweet-talking and hymn-singing persona that wins him to the locals and to Willa, though John sees through his disguise. Not all who wear the collar are men of the cloth. Mrs Cooper's warnings are apropos. There are wolves in sheep's clothing out there waiting to deceive even the elect (Matt. 24:24). Such "preachers" are dangerous. We can know them by their fruit. They may sound good, even perfect, but such goodness must be put to the test. Is the fruit good? In Harry's case, all his fruit was bad, a string of dead bodies lying in his past.

After he has married Willa, Harry needs to get the secret of the hiding place from the children. But John's discernment keeps both his and Pearls' lips sealed. Behind closed doors Harry drops his mask. He is not the blessed peace-loving man of God others see him as. One scene is as chilling as the shower scene in Psycho. With the two kids hiding in the cellar, Harry croons, "I can hear you whisperin' children, so I know you're down there. I can feel myself gettin' awful mad. I'm out of patience children. I'm coming to find you." Then he calls out in a normal voice, "Chill. . . dren!" That long-drawn out word sends shivers down my spine. It evokes all the evil of Lucifer.

After he has married Willa, Harry needs to get the secret of the hiding place from the children. But John's discernment keeps both his and Pearls' lips sealed. Behind closed doors Harry drops his mask. He is not the blessed peace-loving man of God others see him as. One scene is as chilling as the shower scene in Psycho. With the two kids hiding in the cellar, Harry croons, "I can hear you whisperin' children, so I know you're down there. I can feel myself gettin' awful mad. I'm out of patience children. I'm coming to find you." Then he calls out in a normal voice, "Chill. . . dren!" That long-drawn out word sends shivers down my spine. It evokes all the evil of Lucifer.Harry is a twisted man. On his wedding night he tells Willa, his new bride, "Marriage to me represents the blending of two spirits in the sight of Heaven." Then focusing on the physical, her body, he tells her, "That body was meant for begettin' children. It was not meant for the lust of men!" To him, sex for pleasure is sinful, even in the context of the marriage bed. Ironically, in an early conversation with God, he recounts, "There are things you do hate, Lord. Perfume-smellin' things, lacy things, things with curly hair" yet later is caught in the audience of an exotic-dancing club watching a dancer in lacy clothing.

Harry's theology of marriage is errant. God did not bring man and woman together just for procreation. Procreation and reproduction is one aspect of marriage (Gen. 1:28). But companionship and partnership is another (Gen. 2:18). Solomon paints a very clear picture of the beauty and joy of sex within the boundaries of wedlock in his wonderful Song of Solomon. Paul, addressing the topic of sex within marriage, tells the church at Corinth, "Do not deprive each other except by mutual consent and for a time, so that you may devote yourselves to prayer. Then come together again so that Satan will not tempt you because of your lack of self-control" (1 Cor. 7:5). The writer of Hebrews also points out that Marriage should be honored by all, and the marriage bed kept pure" (Heb. 13:4).

Harry's theology of marriage is errant. God did not bring man and woman together just for procreation. Procreation and reproduction is one aspect of marriage (Gen. 1:28). But companionship and partnership is another (Gen. 2:18). Solomon paints a very clear picture of the beauty and joy of sex within the boundaries of wedlock in his wonderful Song of Solomon. Paul, addressing the topic of sex within marriage, tells the church at Corinth, "Do not deprive each other except by mutual consent and for a time, so that you may devote yourselves to prayer. Then come together again so that Satan will not tempt you because of your lack of self-control" (1 Cor. 7:5). The writer of Hebrews also points out that Marriage should be honored by all, and the marriage bed kept pure" (Heb. 13:4).Indeed, Harry's whole belief system is a mess of self-deception. When asked what religion he preaches, he says, "The religion the Almighty and me worked out betwixt us." He claims to have negotiated a form of theology with God. But that is not for man to do. God has given us his Word and his gospel. We cannot create our own religion or theology and believe we have salvation, although many try. Harry reminds us a little of Jim Jones, who created his own cult following and them led them to drink the Kool-Aid to their own demise. Jones had his own theology, his own religion. His followers were "saved" in this man-made way. Harry's own religion led a number of women to their deaths at his hands. The end destination of all cults is man-made salvation, which is death.

Luke wrote, "Salvation is found in no one else, for there is no other name under heaven given to men by which we must be saved" (Acts 4:12). Jesus will not work out a new religion with any of us. We must choose to accept his gospel and his salvation. Anything else is false religion peddled by false preachers . . . just like Harry.

Copyright ©2010, Martin Baggs

Whittaker inhabits the role and character of Amin in an intense and scary way. He is totally believable as a monster, a man-child of sorts, and worthily won the 2007 Oscar for Best Actor. He shows Amin deluding even himself as despot. His egocentrism is clear in his self-anointed title, "His Excellency President for Life, Field Marshal Al Hadji Doctor Idi Amin, VC, DSO, MC, Lord of All the Beasts of the Earth and Fishes of the Sea, and Conqueror of the British Empire in Africa in General and Uganda in Particular."

Whittaker inhabits the role and character of Amin in an intense and scary way. He is totally believable as a monster, a man-child of sorts, and worthily won the 2007 Oscar for Best Actor. He shows Amin deluding even himself as despot. His egocentrism is clear in his self-anointed title, "His Excellency President for Life, Field Marshal Al Hadji Doctor Idi Amin, VC, DSO, MC, Lord of All the Beasts of the Earth and Fishes of the Sea, and Conqueror of the British Empire in Africa in General and Uganda in Particular." In a freak circumstance Nicholas tends to Amin's hand in an emergency. When Amin discovers he is Scottish, he is elated. Amin has an unexpected passion for Scottish culture and all that is Scottish. He invites Nicholas to become his personal physician, living in luxury in Kampala. Though he initially declines, feeling an obligation to the team he has come to work with, the smooth words and sensual living are enough to persuade him to change his mind.

In a freak circumstance Nicholas tends to Amin's hand in an emergency. When Amin discovers he is Scottish, he is elated. Amin has an unexpected passion for Scottish culture and all that is Scottish. He invites Nicholas to become his personal physician, living in luxury in Kampala. Though he initially declines, feeling an obligation to the team he has come to work with, the smooth words and sensual living are enough to persuade him to change his mind. Yet for all this charm, Nicholas finds his dream life has become a walking nightmare of betrayal and madness. He himself has crossed the line and has become Amin's white monkey. Now, Amin won't let him leave. He is a captive, a prisoner in a prison without bars. As Amin woos the press, Nicholas stands with him, fearing for his life and wondering how to escape.

Yet for all this charm, Nicholas finds his dream life has become a walking nightmare of betrayal and madness. He himself has crossed the line and has become Amin's white monkey. Now, Amin won't let him leave. He is a captive, a prisoner in a prison without bars. As Amin woos the press, Nicholas stands with him, fearing for his life and wondering how to escape.

Shyamalan, known for his twist endings, has brought a galaxy of stars into this film. Joacquin Phoenix is strong and silent, conveying emotion through expression more than words, as the lead character Lucius Hunt. Bryce Dallas Howard, daughter of Ron Howard, makes her screen debut as Lucius' love interest, Ivy Walker. She is as vocal as Lucius is quiet, probably because she is blind. William Hurt plays her father Edward Walker, one of the elders of the community, and Sigourney Weaver (

Shyamalan, known for his twist endings, has brought a galaxy of stars into this film. Joacquin Phoenix is strong and silent, conveying emotion through expression more than words, as the lead character Lucius Hunt. Bryce Dallas Howard, daughter of Ron Howard, makes her screen debut as Lucius' love interest, Ivy Walker. She is as vocal as Lucius is quiet, probably because she is blind. William Hurt plays her father Edward Walker, one of the elders of the community, and Sigourney Weaver (

There is something more at the heart of The Village. As Lucius tells his mother, "There are secrets in every corner of this village." These secrets hide things, items the person does not want known or things the person does not want to recall. Sometimes we do that. We keep secrets, we hide sins thinking if we bury them somewhere no one else can see them they will go away. But sin has a nasty habit of reappearing, just when we think we have it licked. Sin can be forgiven. We know that. Jesus told us that (Matt. 26:28). There is no sin that we cannot confess and receive grace and forgiveness for (1 Jn. 1:9). But sins, like bad habits, require more than simple will power to conquer. They need the power of the Spirit. We have access to this power when we call out to Jesus. God has provided a way out for us to escape temptation and sin, if we look for it (1 Cor. 10:13-14).

There is something more at the heart of The Village. As Lucius tells his mother, "There are secrets in every corner of this village." These secrets hide things, items the person does not want known or things the person does not want to recall. Sometimes we do that. We keep secrets, we hide sins thinking if we bury them somewhere no one else can see them they will go away. But sin has a nasty habit of reappearing, just when we think we have it licked. Sin can be forgiven. We know that. Jesus told us that (Matt. 26:28). There is no sin that we cannot confess and receive grace and forgiveness for (1 Jn. 1:9). But sins, like bad habits, require more than simple will power to conquer. They need the power of the Spirit. We have access to this power when we call out to Jesus. God has provided a way out for us to escape temptation and sin, if we look for it (1 Cor. 10:13-14).

Although Tarantino views this as much a spaghetti western as a war film, it is fundamentally a revenge film. It encompasses revenge from two perspectives: national and personal. Raine portrays the national perspective. In his "pep talk" to his new band of brothers, he says:

Although Tarantino views this as much a spaghetti western as a war film, it is fundamentally a revenge film. It encompasses revenge from two perspectives: national and personal. Raine portrays the national perspective. In his "pep talk" to his new band of brothers, he says: Raine and Landa provide a contrasting pair of soldiers, and actors. Where Brad Pitt brings a weird Tennessee twang to his role, and looks nothing like the heart-throb star of earlier movies (such as

Raine and Landa provide a contrasting pair of soldiers, and actors. Where Brad Pitt brings a weird Tennessee twang to his role, and looks nothing like the heart-throb star of earlier movies (such as  Shosanna represents the picture of personal revenge. Having escaped from the Jew-hunter in 1941, we later see her under a pseudonym in Paris running a cinema in 1944. She wants revenge on the Nazis in general and Landa in particular for the loss of her family. It is personal for her.

Shosanna represents the picture of personal revenge. Having escaped from the Jew-hunter in 1941, we later see her under a pseudonym in Paris running a cinema in 1944. She wants revenge on the Nazis in general and Landa in particular for the loss of her family. It is personal for her.

ng with von Bulow he highlights his major advantage, "You do have one thing in your favor: everybody hates you." And this is so true. Von Bulow is a very unlikable fellow. With his wife and step-children he is cold and callous, indifferent, it seems, to their problems. Irons gives a stunning portrait of icy brittleness and won the Best Actor Oscar for this role.

ng with von Bulow he highlights his major advantage, "You do have one thing in your favor: everybody hates you." And this is so true. Von Bulow is a very unlikable fellow. With his wife and step-children he is cold and callous, indifferent, it seems, to their problems. Irons gives a stunning portrait of icy brittleness and won the Best Actor Oscar for this role. Along with the wealth comes an enhanced set of expectations. Von Bulow assumes that even if his appeal is denied, he will be allowed the liberty of time to settle his affairs. He simply cannot picture himself as a common criminal.

Along with the wealth comes an enhanced set of expectations. Von Bulow assumes that even if his appeal is denied, he will be allowed the liberty of time to settle his affairs. He simply cannot picture himself as a common criminal. Yet, for all the rhetoric about the equality and fairness of the system, the truth is that money makes a difference. Without his wealth, von Bulow would not have been able to hire Dershowitz and his team of students and experts. Running this case from his home, Dershowitz surrounds himself with the best students and lawyers to complete the prep work needed to launch his appeal before the Rhode Island Supreme Court. An average defendant convicted would likely be bankrupt from the first trial and unable to raise this kind of legal team. Money counts, especially here.

Yet, for all the rhetoric about the equality and fairness of the system, the truth is that money makes a difference. Without his wealth, von Bulow would not have been able to hire Dershowitz and his team of students and experts. Running this case from his home, Dershowitz surrounds himself with the best students and lawyers to complete the prep work needed to launch his appeal before the Rhode Island Supreme Court. An average defendant convicted would likely be bankrupt from the first trial and unable to raise this kind of legal team. Money counts, especially here.

The police are of no use and so it is to the fledgling FBI that enforcement authorities look. J. Edgar Hoover (Billy Crudup) appoints Melvin Purvis (Christian Bale,

The police are of no use and so it is to the fledgling FBI that enforcement authorities look. J. Edgar Hoover (Billy Crudup) appoints Melvin Purvis (Christian Bale,  Despite this apparent popularity, his arrogance is jarring, even if it is real. His willingness to walk into police stations, though being the most wanted man in America, shows sheer audacity . . . or stupidity. The fact that he gets away with it is testament to the lack of communication and watchfulness in those days. And it is this arrogance, combined with the gruffness of Purvis, that defeats the emotional connection of the audience with either man. Which is the hero? Who do we really care about and cheer for? Neither really. And the script leaves us feeling that both characters could have been more developed and hence more intriguing.

Despite this apparent popularity, his arrogance is jarring, even if it is real. His willingness to walk into police stations, though being the most wanted man in America, shows sheer audacity . . . or stupidity. The fact that he gets away with it is testament to the lack of communication and watchfulness in those days. And it is this arrogance, combined with the gruffness of Purvis, that defeats the emotional connection of the audience with either man. Which is the hero? Who do we really care about and cheer for? Neither really. And the script leaves us feeling that both characters could have been more developed and hence more intriguing. It is when Dillinger falls in love with a coat-check clerk, Billie Frechette (Marion Cotillard,

It is when Dillinger falls in love with a coat-check clerk, Billie Frechette (Marion Cotillard,

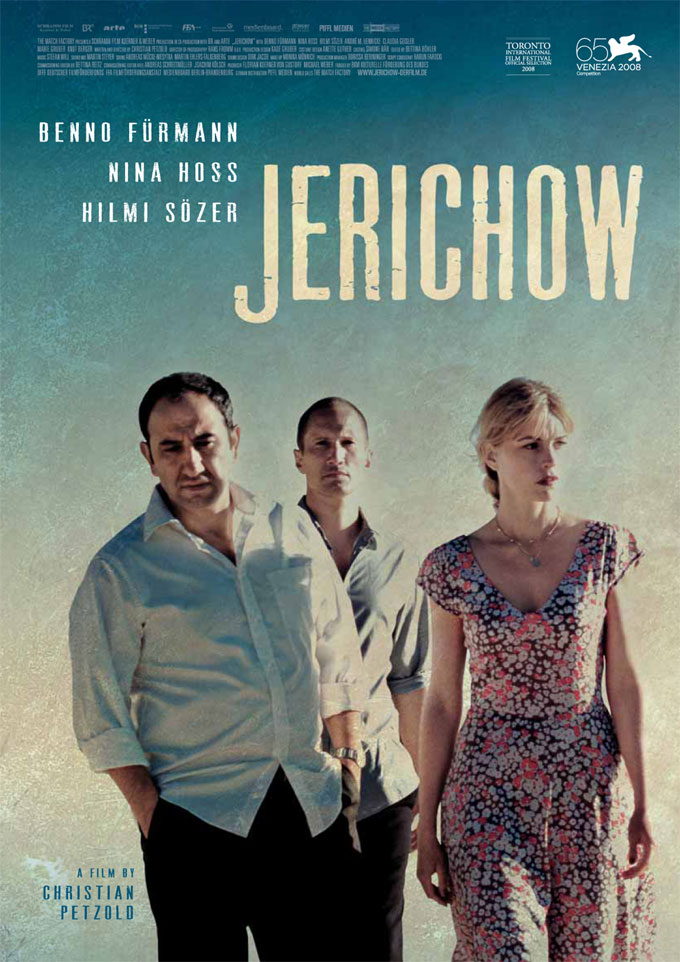

Knowing the original storyline, it is inevitable that Thomas is attracted to Laura, the femme fatale. His attraction turns into passion when Ali has to be brought home drunk by the two of them. This classic love triangle unfolds amidst jealousy and mistrust.

Knowing the original storyline, it is inevitable that Thomas is attracted to Laura, the femme fatale. His attraction turns into passion when Ali has to be brought home drunk by the two of them. This classic love triangle unfolds amidst jealousy and mistrust. Eventually we do learn some secrets from Laura and Ali, but Thomas remains an enigma. Strong, silent and handsome, it is hard to feel for him as we simply don't know him. None of the three are particularly likable.

Eventually we do learn some secrets from Laura and Ali, but Thomas remains an enigma. Strong, silent and handsome, it is hard to feel for him as we simply don't know him. None of the three are particularly likable.

There are a number of clear biblical or moral themes in this movie, and this is the first. With life becoming once more difficult, little things have become precious. The wet wipes from a fast-food restaurant, once a throw-away item, are now valuable in the absence of shower water. In today's America, most of us have way more things and stuff than we need. This is partly a result of the ubiquitous advertising that drums a subconscious message to us that we need more to be satisfied and fulfilled. It is partly a result of our inherent greed and lust for more. The result is the same, though. We are rich without knowing it. We place little value on things because we have so much. When scarcity comes, if it does, these things become useful, and the things we value highly, like our mindless entertainment, becomes useless and irrelevant.

There are a number of clear biblical or moral themes in this movie, and this is the first. With life becoming once more difficult, little things have become precious. The wet wipes from a fast-food restaurant, once a throw-away item, are now valuable in the absence of shower water. In today's America, most of us have way more things and stuff than we need. This is partly a result of the ubiquitous advertising that drums a subconscious message to us that we need more to be satisfied and fulfilled. It is partly a result of our inherent greed and lust for more. The result is the same, though. We are rich without knowing it. We place little value on things because we have so much. When scarcity comes, if it does, these things become useful, and the things we value highly, like our mindless entertainment, becomes useless and irrelevant. Carnegie is after this rumored Bible. Is he a man of God? No! He is old enough to remember the power present in the Word and thinks of it as the ultimate weapon, one able to control men. He is correct: "For the word of God is living and active. Sharper than any double-edged sword, it penetrates even to dividing soul and spirit, joints and marrow; it judges the thoughts and attitudes of the heart" (Heb. 4:12). It is a weapon that can go on the offense in this way. But it is not a weapon that can be employed by men willy-nilly. God does not permit this. In the early days of the church a man named Simon wanted to use the power of God, the Holy Spirit, for his own purposes, even trying to buy it with money (Acts 8:9-25). But God is not commercial in his sharing of power.

Carnegie is after this rumored Bible. Is he a man of God? No! He is old enough to remember the power present in the Word and thinks of it as the ultimate weapon, one able to control men. He is correct: "For the word of God is living and active. Sharper than any double-edged sword, it penetrates even to dividing soul and spirit, joints and marrow; it judges the thoughts and attitudes of the heart" (Heb. 4:12). It is a weapon that can go on the offense in this way. But it is not a weapon that can be employed by men willy-nilly. God does not permit this. In the early days of the church a man named Simon wanted to use the power of God, the Holy Spirit, for his own purposes, even trying to buy it with money (Acts 8:9-25). But God is not commercial in his sharing of power. The Word of God is also a powerful defensive weapon. When tempted by the devil after spending 40 days and nights fasting in the desert, Jesus replied with words from Scripture (Matt. 4:1-11). Despite the temptations, the words of the Bible proved sufficient to defend himself from attack. Eli finds the Book powerful as a defensive weapon in a number of instances, though it is clearly the power of the living God that is at work on his behalf.

The Word of God is also a powerful defensive weapon. When tempted by the devil after spending 40 days and nights fasting in the desert, Jesus replied with words from Scripture (Matt. 4:1-11). Despite the temptations, the words of the Bible proved sufficient to defend himself from attack. Eli finds the Book powerful as a defensive weapon in a number of instances, though it is clearly the power of the living God that is at work on his behalf. But The Book of Eli is not preachy, calling us to accept a gospel. Using Solara, the daughter of his concubine Claudia (Jennifer Beals), Carnegie discovers that Eli has the long-sought book. This sets up the various violent encounters and set pieces that many Christians will find questionable. The brawl in the saloon takes little time but leaves many dead or maimed on the floor. The gunfight in the high street is quick and bloody. The extended shootout at an isolated ranch is thrilling and realistic. And there is the early savage fight with the cannibals that left them harmless, armless and dead.

But The Book of Eli is not preachy, calling us to accept a gospel. Using Solara, the daughter of his concubine Claudia (Jennifer Beals), Carnegie discovers that Eli has the long-sought book. This sets up the various violent encounters and set pieces that many Christians will find questionable. The brawl in the saloon takes little time but leaves many dead or maimed on the floor. The gunfight in the high street is quick and bloody. The extended shootout at an isolated ranch is thrilling and realistic. And there is the early savage fight with the cannibals that left them harmless, armless and dead.

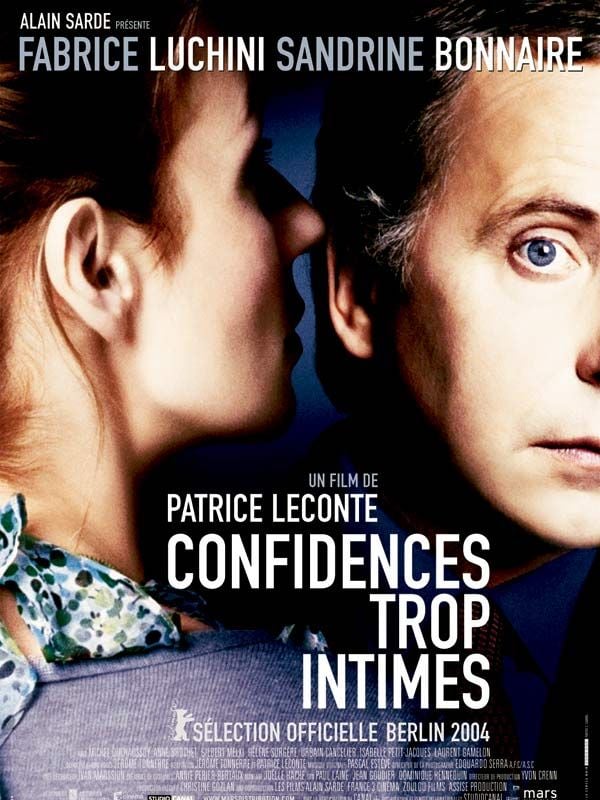

Leconte gives a slow and gentle meditation on loneliness. As he did in

Leconte gives a slow and gentle meditation on loneliness. As he did in  However, Anna has an impact on William. She touches something deep inside his soul and causes a flicker of life. And despite acting as "therapist" for Anna, William seeks out the counsel of Dr. Monnier (Michel Duchaussoy), the therapist Anna was originally supposed to visit. He wants to know how to help her. Dr. Monnier offers William some sage advice, "It's the patient's job to lead the hunt for clues. The psychoanalyst knows nothing. He knows the patient knows but the patient doesn't. See?"

However, Anna has an impact on William. She touches something deep inside his soul and causes a flicker of life. And despite acting as "therapist" for Anna, William seeks out the counsel of Dr. Monnier (Michel Duchaussoy), the therapist Anna was originally supposed to visit. He wants to know how to help her. Dr. Monnier offers William some sage advice, "It's the patient's job to lead the hunt for clues. The psychoanalyst knows nothing. He knows the patient knows but the patient doesn't. See?" Listening, though, can be good and bad. William shows both types in his daily work. As he becomes fixated on Anna, his interviews with clients become unimportant to him. Poor listening tunes these people out. They are talking, but William is not really listening. The sound hushes and we cannot even hear them clearly. How often do we listen without really hearing? Our spouse may tell us something while we are surfing the web and we nod and grunt but avoid listening. We are pretending to listen. On the other hand, when Anna is talking William is completely present. He is listening, engrossed in what she has to say. This is the kind of attentive listening we need to give to our spouses. When we do this, we are picking up every word, each subtle nuance, even the unspoken communication of body language.

Listening, though, can be good and bad. William shows both types in his daily work. As he becomes fixated on Anna, his interviews with clients become unimportant to him. Poor listening tunes these people out. They are talking, but William is not really listening. The sound hushes and we cannot even hear them clearly. How often do we listen without really hearing? Our spouse may tell us something while we are surfing the web and we nod and grunt but avoid listening. We are pretending to listen. On the other hand, when Anna is talking William is completely present. He is listening, engrossed in what she has to say. This is the kind of attentive listening we need to give to our spouses. When we do this, we are picking up every word, each subtle nuance, even the unspoken communication of body language.

Hogarth's initial response to the Iron Giant is the same as that of the town: fear. But when he saves its life, it recognizes he is a friend. The innocence of the alien robot and its friendship with Hogarth is juxtaposed by the alienation of Hogarth from other kids his age. He has retreated into imagination, and the Giant seems to be an answer to his prayers.

Hogarth's initial response to the Iron Giant is the same as that of the town: fear. But when he saves its life, it recognizes he is a friend. The innocence of the alien robot and its friendship with Hogarth is juxtaposed by the alienation of Hogarth from other kids his age. He has retreated into imagination, and the Giant seems to be an answer to his prayers. This kind of friendship changes us. As Hogarth begins teaching the Iron Giant (voice of Vin Diesel) words and simple speech, the Giant asks questions that provoke serious thought. When hunters kill a bambi-like deer, the subject of death emerges. The Giant asks, "You die?" and Hogath responds in innocence, "Well, yes, someday." The Giant thinks about this and asks another question, "I die?" That is more difficult: "I don't know. You're made of metal, but you have feelings, and you think about things, and that means you have a soul. And souls don't die." Is this robot alive? According to Hogarth he is, and he possesses a soul.

This kind of friendship changes us. As Hogarth begins teaching the Iron Giant (voice of Vin Diesel) words and simple speech, the Giant asks questions that provoke serious thought. When hunters kill a bambi-like deer, the subject of death emerges. The Giant asks, "You die?" and Hogath responds in innocence, "Well, yes, someday." The Giant thinks about this and asks another question, "I die?" That is more difficult: "I don't know. You're made of metal, but you have feelings, and you think about things, and that means you have a soul. And souls don't die." Is this robot alive? According to Hogarth he is, and he possesses a soul. What is theologically true, regardless of understanding of soul, is that souls never die. Hogarth is right about this. We all will die. Our bodies will be laid in the grave and worms will feast on them. But death will separate our spirits and souls from our bodies causing them to move to their future destinies: some to be with the Lord, later to be re-embodied in an eternal body in a heavenly existence, some to be apart from the Lord, also re-embodied but in a hellish existence.

What is theologically true, regardless of understanding of soul, is that souls never die. Hogarth is right about this. We all will die. Our bodies will be laid in the grave and worms will feast on them. But death will separate our spirits and souls from our bodies causing them to move to their future destinies: some to be with the Lord, later to be re-embodied in an eternal body in a heavenly existence, some to be apart from the Lord, also re-embodied but in a hellish existence. Mansley rents the bedroom in the Hughes house from Hogarth's mom, Annie (voice of Jennifer Aniston). This gives him opportunity to threaten the boy and discover the Giant's location, setting up the climax. And it is in this moment, when the town is truly under attack, that the Iron Giant's Christ-figure motif becomes readily apparent. And in contrast, the "good" American agent is seen to be a selfish and paranoid coward.

Mansley rents the bedroom in the Hughes house from Hogarth's mom, Annie (voice of Jennifer Aniston). This gives him opportunity to threaten the boy and discover the Giant's location, setting up the climax. And it is in this moment, when the town is truly under attack, that the Iron Giant's Christ-figure motif becomes readily apparent. And in contrast, the "good" American agent is seen to be a selfish and paranoid coward.