Director: Gregory Hoblit, 1998.

Not too many Hollywood films have explicit themes that are religious in nature. Religion, though an integral part of the lives of many people worldwide, is politically incorrect as a topic or theme in the West. Yet Hoblit's Fallen is overtly religious dealing with faith and demons. As a supernatural thriller it is engaging and effective. As a primer on biblical theology it is less effective.

Denzel Washington (The Taking of Pelham 1-2-3) plays Detective John Hobbes, a homicide cop who struggles with the big philosophical and theological questions of life, like "Why are we here?" His divorce has left him alone, living with his brother and nephew. His partner, Jonesy (John Goodman, Barton Fink), is a foil to allow Hobbes to ponder these questions. Interestingly, Hobbes' name is taken from the combination of two 17th century philosphers, Thomas Hobbes and John Locke. These both explored the innate nature of humanity, whether evil or rational and good. And these are themes explored in Fallen.

After an opening scene that leaves us wondering about Denzel Washington's character (Detective John Hobbes), we flashback in time to see him visiting a condemned killer he captured, Edgar Reese (Elias Koteas). Hobbes is the one on the outside of the cell, but Reese acts as though Hobbes is the one trapped and imprisoned. Indeed, Reese is arrogant and cocky, confidently shaking Hobbes' hand though death is only minutes away. As he skips to his execution he sings, "Time is on my side," a key song throughout. And before he is put to death he touches the executioner.

After an opening scene that leaves us wondering about Denzel Washington's character (Detective John Hobbes), we flashback in time to see him visiting a condemned killer he captured, Edgar Reese (Elias Koteas). Hobbes is the one on the outside of the cell, but Reese acts as though Hobbes is the one trapped and imprisoned. Indeed, Reese is arrogant and cocky, confidently shaking Hobbes' hand though death is only minutes away. As he skips to his execution he sings, "Time is on my side," a key song throughout. And before he is put to death he touches the executioner.Hobbes thinks the string of serial murders has run its course, but how wrong he is. When a clue whispered to him by Reese shows up written on the wall of another murder victim, Hobbes begins to question what is going on. Something is happening that appears evident only to him.

And that brings us to one of the themes and points of contact with biblical Christianity. Hobbes says it, "Something is always happening, but when it happens, people don't always see it, or understand it, or accept it." It takes him a while but he begins to see. Our eyes are closed to the unusual and invisible. We see what we expect to see. But many times things are hiding in plain sight. The supernatural, the immaterial, is not visible to the eyes in our head. But they are visible to the eyes of faith. The prophet Elisha saw the chariots of fire that surrounded his city although his servant did not (2 Kings 6:16). When Elisha prayed God opened his servant's eyes of faith to see what Elijah already knew was there (2 Kings 6:17). It often takes faith to see things.

And that brings us to one of the themes and points of contact with biblical Christianity. Hobbes says it, "Something is always happening, but when it happens, people don't always see it, or understand it, or accept it." It takes him a while but he begins to see. Our eyes are closed to the unusual and invisible. We see what we expect to see. But many times things are hiding in plain sight. The supernatural, the immaterial, is not visible to the eyes in our head. But they are visible to the eyes of faith. The prophet Elisha saw the chariots of fire that surrounded his city although his servant did not (2 Kings 6:16). When Elisha prayed God opened his servant's eyes of faith to see what Elijah already knew was there (2 Kings 6:17). It often takes faith to see things.Sometimes, though, we see things that don't match our experience and disregard or ignore them because they don't fit our paradigm. This happens to Hobbes. As his investigation into the next several murders escalates it seems that the killer has the exact same modus operandi as Reese. Yet Reese is dead; Hobbes saw that with his own eyes. Something else is behind these chilling crimes.

Hobbes visits Gretta Milano (Embeth Davidz, Junebug), a theology professor and daughter of a dead detective. Asking questions about her father's death, Hobbes pries into a past she wants left alone. As she verbally spars with him, she asks, "You believe in God?" This is a strange question to ask a homicide detective, although coming from a theologian perhaps it is not unusual. Hobbes responds, "Just Sundays. My job, seeing what I see, faith isn't easy to sustain." We are back to seeing. He has become jaded and cynical from seeing too much evil and its effects. But Gretta says, "What you see in your job is nothing." His physical eyes are open but his spiritual eyes are blind.

Hobbes visits Gretta Milano (Embeth Davidz, Junebug), a theology professor and daughter of a dead detective. Asking questions about her father's death, Hobbes pries into a past she wants left alone. As she verbally spars with him, she asks, "You believe in God?" This is a strange question to ask a homicide detective, although coming from a theologian perhaps it is not unusual. Hobbes responds, "Just Sundays. My job, seeing what I see, faith isn't easy to sustain." We are back to seeing. He has become jaded and cynical from seeing too much evil and its effects. But Gretta says, "What you see in your job is nothing." His physical eyes are open but his spiritual eyes are blind.Gretta's question is pertinent to us. Do we believe in God? That is one of the fundamental questions of life. How we answer it will steer how we live our lives. Of course, as a follower of Jesus I affirm the existence of God (Heb. 11:6), the God of the Bible (Gen. 1:1). He is there if we seek him (Deut. 4:29). But it takes faith to find him and to come into relationship with him through Jesus (Jn. 14:6). Faith itself is fundamental to life. If we do not believe in God, like so many atheists, that disbelief itself is an act of faith. When we ride in our cars we have faith that our brakes will stop us before we plow into the car stopped at the red light in front of us. We cannot avoid faith. The real question is, in what or in whom do we place our faith? Hobbes placed his faith in what he could see. He was a pragmatist. But that would change.

As Hobbes' eyes begin to open he realizes that there is something sinister and supernatural behind the events and the murders. He suspects a demon named Azazel is possessing the killers. With no one to turn to with these "non-rational" thoughts, he takes his suspicions to Gretta for her assessment. "I believe more is hidden than is seen," she tells him. Hobbes is still not ready to see the spiritual in the physical world: "Well I believe what I see, but I'm still trying to get my mind around what I just saw."

As Hobbes' eyes begin to open he realizes that there is something sinister and supernatural behind the events and the murders. He suspects a demon named Azazel is possessing the killers. With no one to turn to with these "non-rational" thoughts, he takes his suspicions to Gretta for her assessment. "I believe more is hidden than is seen," she tells him. Hobbes is still not ready to see the spiritual in the physical world: "Well I believe what I see, but I'm still trying to get my mind around what I just saw."At its heart, Fallen is about opening the eyes of faith. A demon is an invisible spiritual being that is personal and usually stronger than people. The Bible presents demons as a reality (Matt. 8:16). They were originally created as angels who were good but rebelled against God, their creator, and chose to follow Lucifer, or Satan, the chief opponent of the Lord (Rev. 12:7-9, Jude 6). In their rebellion they have fallen, hence the title.

These fallen angels can possess humans. There are many examples of this in the gospel accounts (Mk. 1:32; 5:18; 7:26). Part of the ministry of Jesus and his disciples was to cast out these demons, freeing the demonized (Matt. 9:32-33). It is clear that they can move from host to host; when the demons were cast out of the two demoniacs of Gadarenes, Jesus cast them into a herd of swine (Matt. 8:28-32). But exactly how they pass from person to person is not elaborated in the Bible. A means is postulated in Fallen, as this plays an important role in the film.

As a thriller with a shocking ending, Fallen works well. And hopefully it opens some eyes to the unseen reality of the spirit world that surrounds us. If so, it moves us towards a crisis of faith, as it did for Hobbes. Are you seeing yet?

Copyright ©2009, Martin Baggs

Certainly there is an aspect of humanity that is immaterial. Biblically, men and women are multi-dimensional in composition (1 Thess. 5:23, Heb. 4:12), but there is disagreement as to the numberof the components. At its broadest level, all Christians agree that we are made up of a material aspect (body) and an immaterial aspect (soul or spirit). Some see a difference between the soul and spirit. Dallas Willard, a philosophy professor at USC, has a model of the human constitution with 5 elements: spirit, mind, body, social context, and soul ("Renovation of the Heart"). In his model, the soul is the core dimension that interrelates all the other dimensions of a person to integrate into one holistic life.

Certainly there is an aspect of humanity that is immaterial. Biblically, men and women are multi-dimensional in composition (1 Thess. 5:23, Heb. 4:12), but there is disagreement as to the numberof the components. At its broadest level, all Christians agree that we are made up of a material aspect (body) and an immaterial aspect (soul or spirit). Some see a difference between the soul and spirit. Dallas Willard, a philosophy professor at USC, has a model of the human constitution with 5 elements: spirit, mind, body, social context, and soul ("Renovation of the Heart"). In his model, the soul is the core dimension that interrelates all the other dimensions of a person to integrate into one holistic life. The protagonist of the film is Lyra Belacqua, a young orphan and niece of Asriel being raised by the tutors of Jordan College, Oxford. Dakota Blue Richards gives a strong debut performance and is in almost every scene. Indeed, she carries the movie even when working with the veteran actors like Kidman and Craig. When she overhears her uncle talking about a magic dust only found in the arctic north which opens doorways between parallel universes, she wants to join him in his expedition, but is denied the privilege. Yet, when the mysterious and icy cold Mrs Coulter (Nicole Kidman) offers to take her on a similar journey she jumps at the chance. Before she leaves, the Master of the College gives her the golden compass. When she asks what it is, he replies, "It's an alethiometer. It tells the truth." This is central to this movie.

The protagonist of the film is Lyra Belacqua, a young orphan and niece of Asriel being raised by the tutors of Jordan College, Oxford. Dakota Blue Richards gives a strong debut performance and is in almost every scene. Indeed, she carries the movie even when working with the veteran actors like Kidman and Craig. When she overhears her uncle talking about a magic dust only found in the arctic north which opens doorways between parallel universes, she wants to join him in his expedition, but is denied the privilege. Yet, when the mysterious and icy cold Mrs Coulter (Nicole Kidman) offers to take her on a similar journey she jumps at the chance. Before she leaves, the Master of the College gives her the golden compass. When she asks what it is, he replies, "It's an alethiometer. It tells the truth." This is central to this movie. see the truth (from the Greek, aletheia [αλήθεια], meaning truth) is symbolic of reality. Truth is present, but not all can see it. In Compass, Lyra uses this magical instrument to get at truth, formulating questions for it to answer. In our world, truth is fully embodied in the person of Jesus Christ. He declared, "I am the way and the truth and the life" (Jn. 14:6). Those who look for truth and find Christ find truth. And apart from an alethiometer, we can offer prayers to God seeking wisdom and truth.

see the truth (from the Greek, aletheia [αλήθεια], meaning truth) is symbolic of reality. Truth is present, but not all can see it. In Compass, Lyra uses this magical instrument to get at truth, formulating questions for it to answer. In our world, truth is fully embodied in the person of Jesus Christ. He declared, "I am the way and the truth and the life" (Jn. 14:6). Those who look for truth and find Christ find truth. And apart from an alethiometer, we can offer prayers to God seeking wisdom and truth.

When Rémy's ex-wife calls their son Sébastien (Stéphane Rousseau), a highly successful financial analyst living in London with his girlfriend Gaëlle (Marina Hands,

When Rémy's ex-wife calls their son Sébastien (Stéphane Rousseau), a highly successful financial analyst living in London with his girlfriend Gaëlle (Marina Hands,  When the cancer gets worse and his father's pain becomes acute as well as chronic, Sébastien sets out to find some heroin to ease the pain. With the help of Nathalie (Marie-Josée Croze,

When the cancer gets worse and his father's pain becomes acute as well as chronic, Sébastien sets out to find some heroin to ease the pain. With the help of Nathalie (Marie-Josée Croze,  The barbaric cancer ultimately brought reconciliation between Rémy and Sébastien. The father-son relationship is supposed to be one of love and mutual respect. When death knocks on the door, it is time to put aside bitterness, bury the hatchet, and restore relationships.

The barbaric cancer ultimately brought reconciliation between Rémy and Sébastien. The father-son relationship is supposed to be one of love and mutual respect. When death knocks on the door, it is time to put aside bitterness, bury the hatchet, and restore relationships.

In the opening scene, Caspar introduces the theme: "I'm talkin' about friendship. I'm talkin' about character. I'm talkin' about - hell. Leo, I ain't embarrassed to use the word - I'm talkin' about ethics." Strange as it may seem, these two murderous men have a code of ethics. He adds, in an unrecognized note of irony, "It's gettin' so a businessman can't expect no return from a fixed fight. Now, if you can't trust a fix, what can you trust?"

In the opening scene, Caspar introduces the theme: "I'm talkin' about friendship. I'm talkin' about character. I'm talkin' about - hell. Leo, I ain't embarrassed to use the word - I'm talkin' about ethics." Strange as it may seem, these two murderous men have a code of ethics. He adds, in an unrecognized note of irony, "It's gettin' so a businessman can't expect no return from a fixed fight. Now, if you can't trust a fix, what can you trust?" Tom is the antihero protagonist of this deep, dark movie. Byrne played a similar character in the later

Tom is the antihero protagonist of this deep, dark movie. Byrne played a similar character in the later  This takes us to the other main theme of Miller's Crossing: the heart of the criminal. And Tom is at the center of the question. At one point, Verna tells him, "That's you all over, Tom. A lie and no heart." He thinks he loves her, but this could be lust, not love. He is cold and aloof. Does he have a heart? Can a criminal really have a heart? Or is the criminal cold-hearted and cold-blooded, driven by greed and lust?

This takes us to the other main theme of Miller's Crossing: the heart of the criminal. And Tom is at the center of the question. At one point, Verna tells him, "That's you all over, Tom. A lie and no heart." He thinks he loves her, but this could be lust, not love. He is cold and aloof. Does he have a heart? Can a criminal really have a heart? Or is the criminal cold-hearted and cold-blooded, driven by greed and lust?

night turns dark. She is murdered and he is left unconscious by the attacker. Although initially a suspect, a serial killer is charged with the crime.

night turns dark. She is murdered and he is left unconscious by the attacker. Although initially a suspect, a serial killer is charged with the crime. With a faceless enemy following him apparently aware of his every move, Beck is left wondering who to turn to. He does tell someone: Helene Perkins (Kristin Scott Thomas,

With a faceless enemy following him apparently aware of his every move, Beck is left wondering who to turn to. He does tell someone: Helene Perkins (Kristin Scott Thomas,

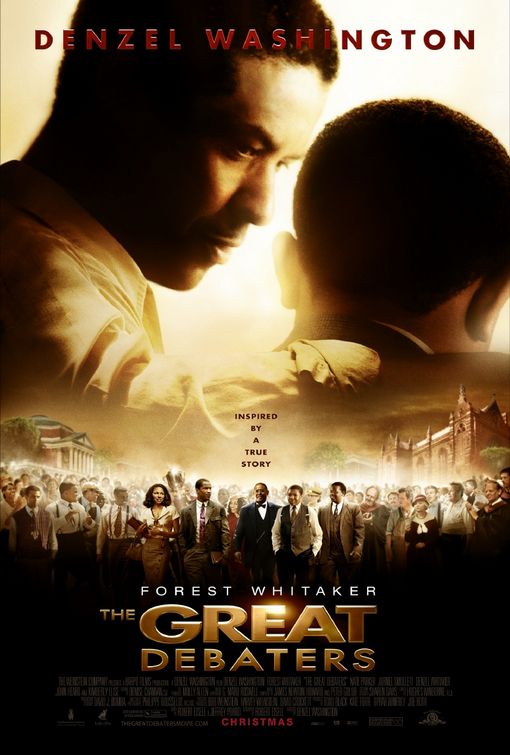

The young actors give outstanding performances, even alongside screen veteran and Oscar winners, Washington and Whitaker. Interestingly, young Denzel Whitaker is named after Denzel Washington but is no relation to Forest Whitaker. But, despite the movie's ethical themes, argued in debate format, it is ultimately lightweight devoid of intellectual depth or argument.

The young actors give outstanding performances, even alongside screen veteran and Oscar winners, Washington and Whitaker. Interestingly, young Denzel Whitaker is named after Denzel Washington but is no relation to Forest Whitaker. But, despite the movie's ethical themes, argued in debate format, it is ultimately lightweight devoid of intellectual depth or argument. As the debate team is formed it needs Tolson's teachings on elocution and discipline. Further, it relies on his development of debate position and logic. But as the team starts winning, the young debaters' confidence soars and they yearn to define their own arguments. As they win against the top black colleges of the time, Tolson wants them to compete against white schools.

As the debate team is formed it needs Tolson's teachings on elocution and discipline. Further, it relies on his development of debate position and logic. But as the team starts winning, the young debaters' confidence soars and they yearn to define their own arguments. As they win against the top black colleges of the time, Tolson wants them to compete against white schools.

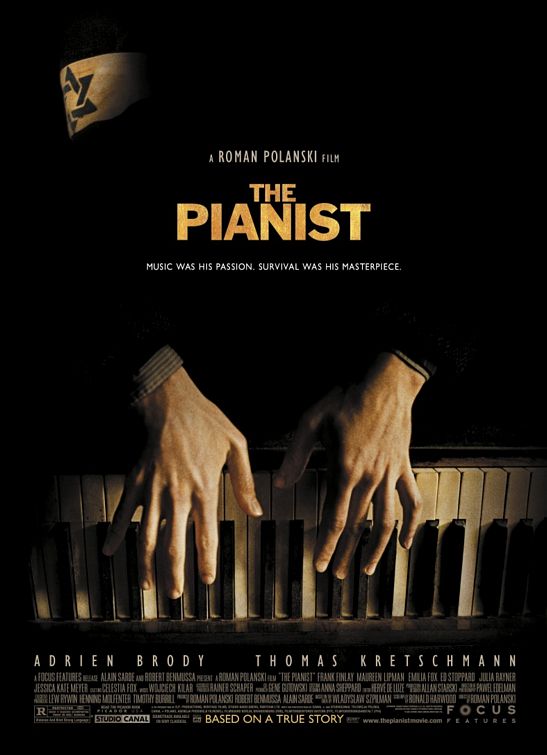

As his life is forced into the overcrowded and underfed conditions in the Warsaw Ghetto, survival becomes paramount. At first he wants to be active in the underground distributing propaganda, but he is told, "You're too well known, Wladek. And you know what? You musicians don't make good conspirators. You're too . . . too . . . musical!" His very essence, his life passion, prevents him from becoming part of the resistance. He can only look on as he plays piano as entertainment in one of the last remaining restaurants for Jews.

As his life is forced into the overcrowded and underfed conditions in the Warsaw Ghetto, survival becomes paramount. At first he wants to be active in the underground distributing propaganda, but he is told, "You're too well known, Wladek. And you know what? You musicians don't make good conspirators. You're too . . . too . . . musical!" His very essence, his life passion, prevents him from becoming part of the resistance. He can only look on as he plays piano as entertainment in one of the last remaining restaurants for Jews. Polanski's use of Chopin throughout the film as the background score is moving and effective. The Polish composer's evoctive music brings a sad mood, yet frosted with a subtle hint of hope. Detweiler comments on a powerful moment: "The scene in which Szpilman discovers an upright piano in his latest safe house affirms the sustaining power of art. Szpilman's private recital drives all the horrors of his reality away."

Polanski's use of Chopin throughout the film as the background score is moving and effective. The Polish composer's evoctive music brings a sad mood, yet frosted with a subtle hint of hope. Detweiler comments on a powerful moment: "The scene in which Szpilman discovers an upright piano in his latest safe house affirms the sustaining power of art. Szpilman's private recital drives all the horrors of his reality away." Toward the end, this arbitrariness directly encounters Szpilman. When he is discovered living in a bombed-out building by a German officer, Captain Wilm Hosenfeld (Thomas Kretschmann,

Toward the end, this arbitrariness directly encounters Szpilman. When he is discovered living in a bombed-out building by a German officer, Captain Wilm Hosenfeld (Thomas Kretschmann,

What follows then is a beautiful montage that shows Carl and Ellie dating, marrying and growing old together, child-less. With no dialog, this short portion is reminiscent of the first half of

What follows then is a beautiful montage that shows Carl and Ellie dating, marrying and growing old together, child-less. With no dialog, this short portion is reminiscent of the first half of  When Carl is forced to abandon his life-long home, the one he shared with Ellie and which contains ghosts of happier times, he decides it is time to throw caution to the winds and follow his dreams, fulfilling the promise he made to her. If he couldn't make it to South America with Ellie he will do it alone with her memory. And he casts off, with thousands of helium-filled balloons taking his house up into the sky and awaiting adventure. What he doesn't count on is a castaway -- Russell (Jordan Nagai), a hapless boy scout looking for one more merit badge.

When Carl is forced to abandon his life-long home, the one he shared with Ellie and which contains ghosts of happier times, he decides it is time to throw caution to the winds and follow his dreams, fulfilling the promise he made to her. If he couldn't make it to South America with Ellie he will do it alone with her memory. And he casts off, with thousands of helium-filled balloons taking his house up into the sky and awaiting adventure. What he doesn't count on is a castaway -- Russell (Jordan Nagai), a hapless boy scout looking for one more merit badge. As Carl and Russell traverse the unexplored territory they are literally held down by the ropes tied to the levitating house. They are carrying the weight of Carl's world on their backs. In one scene, as the balloons start to lose their helium, Carl realizes that the only way for it to go up again is to rid it of excess weight. What a metaphor for life!

As Carl and Russell traverse the unexplored territory they are literally held down by the ropes tied to the levitating house. They are carrying the weight of Carl's world on their backs. In one scene, as the balloons start to lose their helium, Carl realizes that the only way for it to go up again is to rid it of excess weight. What a metaphor for life!

When Hana (Juliette Binoche), a sympathetic Canadian nurse, realizes that he is dying, she gets permission to stay with him in an abandoned monastery in Italy. Left with a pistol and morphine, she sets about trying to keep him alive. And it is in this monastery, reading his book, that the events of his life unfold in flashback, enabling both the patient and the nurse to discover more about themselves.

When Hana (Juliette Binoche), a sympathetic Canadian nurse, realizes that he is dying, she gets permission to stay with him in an abandoned monastery in Italy. Left with a pistol and morphine, she sets about trying to keep him alive. And it is in this monastery, reading his book, that the events of his life unfold in flashback, enabling both the patient and the nurse to discover more about themselves. Further, as we see the patient before his horrific crash, we realize that he was aloof. He rarely let others in emotionally. He remained a mystery even when others knew his name. But in the midst of a sudden sandstorm in the desert this mystery man finds himself in a car with Katherine Clifton (Kristin Scott Thomas), the wife of one his explorer colleagues. And it is here that we begin to see the pent-up passion that lurks beneath the surface. This passion slowly emerges into a tragic love affair that smolders on the screen.

Further, as we see the patient before his horrific crash, we realize that he was aloof. He rarely let others in emotionally. He remained a mystery even when others knew his name. But in the midst of a sudden sandstorm in the desert this mystery man finds himself in a car with Katherine Clifton (Kristin Scott Thomas), the wife of one his explorer colleagues. And it is here that we begin to see the pent-up passion that lurks beneath the surface. This passion slowly emerges into a tragic love affair that smolders on the screen.

William H. Macy plays Jerry Lundegaard, a wimp of a man who works for his father-in-law as sales manager at a car dealership. His financial troubles are never explained, but they are significant enough that his only hope is a "simple" criminal activity. But when is crime ever simple? Steve Buscemi is terrific as Carl Showalter, one of the two crooks, partnered with Peter Skomare as the almost silent but trigger-happy Gaear Grimsrud. When the kidnapping occurs and they are fleeing Minneapolis, they are pulled over by a police car and the end result is a triple homicide. Crime leads to crime.

William H. Macy plays Jerry Lundegaard, a wimp of a man who works for his father-in-law as sales manager at a car dealership. His financial troubles are never explained, but they are significant enough that his only hope is a "simple" criminal activity. But when is crime ever simple? Steve Buscemi is terrific as Carl Showalter, one of the two crooks, partnered with Peter Skomare as the almost silent but trigger-happy Gaear Grimsrud. When the kidnapping occurs and they are fleeing Minneapolis, they are pulled over by a police car and the end result is a triple homicide. Crime leads to crime. Marge contrasts sharply with the criminals, including city-slicker Jerry. All three of the criminals are driven by money. Jerry's predicament precipates the crime spree, but the greed of the two kidnappers propels it along. But Marge is different. She tells her husband, "There's more to life than a little money, you know." How true! Money is a commodity. It is not a source of happiness or life. It is necessary, not a dependency. The apostle Paul tells Timothy that "the love of money is a root of all kinds of evil" (1 Tim. 6:10). Money itself is not the problem; our love of money is.

Marge contrasts sharply with the criminals, including city-slicker Jerry. All three of the criminals are driven by money. Jerry's predicament precipates the crime spree, but the greed of the two kidnappers propels it along. But Marge is different. She tells her husband, "There's more to life than a little money, you know." How true! Money is a commodity. It is not a source of happiness or life. It is necessary, not a dependency. The apostle Paul tells Timothy that "the love of money is a root of all kinds of evil" (1 Tim. 6:10). Money itself is not the problem; our love of money is. Marge's simple life is illustrative of her aphorism. She dines at a buffet restaurant with her loving husband, Norm (John Carroll Lynch,

Marge's simple life is illustrative of her aphorism. She dines at a buffet restaurant with her loving husband, Norm (John Carroll Lynch,